William Blair sees ‘market disconnect,’ starts Viking at Outperform. William Blair analyst Andy Hsieh initiated Viking Therapeutics with an Outperform rating saying the company has a differentiated clinical pipeline focusing on modulating hormone receptors in a tissue-specific and receptor-selective fashion. The analyst believes VK2809 is uniquely positioned for treating fatty liver disease or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Further, VK5211 is a non-steroidal, tissue-specific selective androgen receptor modulator that has recently demonstrated the ability to boost lean body mass among patients recovering from hip fracture in a positive Phase II study, the analyst adds. Hsieh sees an “appreciable market disconnect” given the company’s “broad” pipeline. He does not believe the potential of VK2809 and VK5211 is fairly reflected in the stock.

Search This Blog

Monday, April 30, 2018

Sunday, April 29, 2018

Berkeley Fights Harvard, MIT Over Profits From Gene-Editing Tech

- Institutes fight over CRISPR, the ‘discovery of the Century’

- Victory could determine who gets paid for revolutionary idea

Scientists have used the breakthrough gene-editing technology CRISPR to create advances in medicine and agriculture, from ways to eliminate sickle-cell anemia to growing mushrooms that resist browning.

But the battle over who will make money from it is just beginning.

On Monday, some of the most well-known research institutions in the world — including University of California at Berkeley and the Broad Institute, which is affiliated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University — face off in an appeals court in Washington over the question of who invented and thus can profit from the technology.

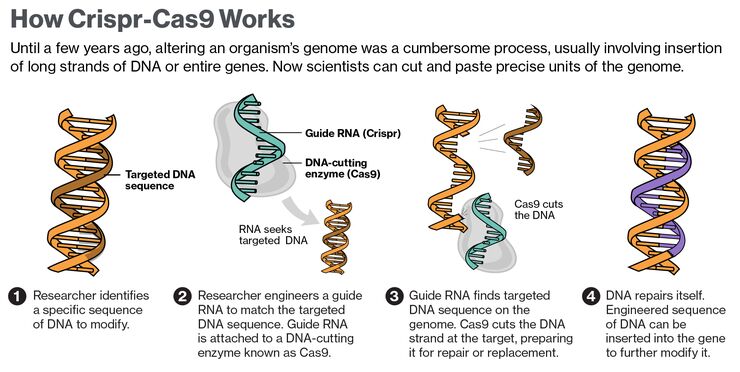

CRISPR, or Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, uses a defense mechanism employed by bacteria to target parts of a gene and cut them out like a pair of molecular scissors. It has already triggered a revolution in the world of genetics by making it easier to manipulate the building blocks of living organisms. The CRISPR breakthrough may one day lead to a Nobel Prize.

What’s unclear is who will reap the potential windfall on royalties for commercial applications in medicines, health treatments and improved foods.

“I’m a company and I want to practice CRISPR, who do I license, who do I pay?” said Kevin Noonan, a biotechnology lawyer with McDonnel Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff in Chicago.

Universities and start-up companies primarily in the U.S. and China are ramping up research using CRISPR. Since 2013, patents have been sought on more than 2,500 CRISPR-related inventions, according to Swiss researchers.

One of them, CRISPR-Cas9, is a naturally-occurring enzyme used by bacteria to rid itself of viruses and was first discovered decades ago.

Researchers with UC Berkeley and the University of Vienna were first to find ways to guide those molecular scissors to targeted locations on the genome and say their work could be used for any living thing. They filed their patent application in 2012 and have called it “the discovery of the century.”

The Broad Institute in Massachusetts, set up by groups including MIT and Harvard to experiment with the human genome, said the UC Berkeley team only showed how the technology would work in a test tube. They said their research team proved CRISPR-cas9 could work in plants and animals, including humans.

The arguments Monday before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit involve the race to patent CRISPR technology. By paying an extra $70 fee, Broad got an accelerated review of its patent applications, which were issued while the application from UC Berkeley was still pending.

UC Berkeley objected, telling the patent office that its application covered all the work Broad claims to have invented. Last year, the patent office disagreed, saying the inventions were different enough that both could get patents. UC Berkeley appealed. A decision expected later this year.

UC Berkeley scientist and co-inventor Jennifer Doudna described the patent office ruling as saying “our patent will be for all tennis balls and Broad’s will be for green tennis balls.” The reason UC Berkeley objects is because those green tennis balls could be where the money is.

“Human therapeutics is really the money maker here,” said Michael Stramiello, a patent lawyer with Paul Hastings in Washington. “The parties involved would like to have a stake there. Certainly in California’s mind, it doesn’t really want to share rights there. If someone ends up with the lion share of rights, that’s extremely valuable.”

Just how valuable is yet unknown, but universities have been richly rewarded for ground-breaking ideas in medicine. Columbia University, where researchers in the 1980s developed a gene-splicing process fundamental to every biotechnology company, collected more than $600 million before its patent expired in 2003.

Proponents expect that CRISPR will change medical care in terms of genetic diseases, a fundamental evolution that will upend existing markets and create entirely new approaches to care that the current health system can’t anticipate.

If you can repair a defect with a one-time therapy, you wipe out the existing market for treating the condition and scale back related doctor and hospital visits. And if you can cut out a precise part of a gene, at some point you might be able to replace it with something else — turning the infection-fighting T-cells into super soldiers that can eradicate cancer, for example. Researchers are looking at ways to alter mosquitos so they don’t carry malaria, treat eye disorders and even modify elephants to bring back woolly mammoths.

“At the end of the day, there’s so much potential with the CRISPR platform to treat so many diseases and have a tremendous effect on the patients,” said Samarth Kulkarni, chief executive officers of Crispr Therapeutics AG, which is developing a treatment for sickle-cell anemia.

Crispr, based in Zug, Switzerland, with operations in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was founded by Emmanuelle Charpentier, one of the inventors on the UC Berkeley side.

DowDuPont

Companies are trying to stay out of the CRISPR patent dispute and avoid the types of litigation wars that enveloped advances in mobile phone technology.

DowDuPont Inc. is using CRISPR to develop corn and soybean crops that repel insects without chemical pesticides and tolerate herbicides for easier weed control, has licenses with both Broad and UCBerkeley.

Crispr and Intellia Therapeutics Inc. have licensed UC Berkeley’s technology, while Editas Medicine Inc. is using Broad’s inventions. The companies also have each sought patents on their own work.

The patent landscape is growing. IPStudies Sarl, a Switzerland-based research group, counted 2,519 CRISPR-related inventions, based on patents and published applications around the world. Applications generally are made public after 18 months.

100 Inventions Per Month

In 2012, the year UC Berkeley announced its discoveries, 71 CRISPR-related patents and applications were made public. Since the end of 2016, the group has identified about 100 new inventions being disclosed every month.

“From a technical standpoint, the CRISPR field has inspired many scientific teams worldwide,” said Corinne Le Buhan, a researcher with IPStudies. Most of the work is being done in the U.S. and China, while Europe “clearly lags behind,” she said.

One group is trying to develop a patent pool that would provide a sort of one-stop shop for anyone wanting to license basic technology, no matter which enzyme variant is used. MPEG LA LLC, better known for a licensing program related to video streaming, said it hopes to announce a CRISPR patent pool later this year.

“The market concerns I have heard is that the CRISPR patent landscape is very large, very confusing and difficult to navigate,” said Kristin Neuman, executive director for Biotechnology Licensing at MPEG LA. “It’s hard to figure out what rights they need to license, who they need to license.”

So far, the affiliated group of Broad, MIT, Harvard and the Rockefeller University are the only entities to publicly agree to join the MPEG LA pool. Neuman declined to name other companies, saying they were promised confidentiality or hadn’t yet fully signed on.

“The Broad Institute already licenses CRISPR-Cas9 non-exclusively for all applications, with the exception of human therapeutics, where we have significantly limited the exclusivity,” Issi Rozen, Broad’s chief business officer, said in a July announcement. “We look forward to working with others to ensure the widest possible access to all key CRISPR intellectual property.”

Fights between universities are rare, but is part of a growing trend of schools and institutes becoming more aggressive in trying to find ways to profit off their research. Universities are under pressure to get money from their patents because “there’s only so much you can charge for tuition,” Noonan said.

So far, the patent question hasn’t hindered work by companies like Crispr Therapeutics to develop new treatments.

“Our primary focus is to develop therapeutics, so I don’t let the intellectual property things distract from the mission,” Kulkarni said. Still, “it would be a shame if these IP wars get in the way. There is plenty of room for people to coexist.”

Silicon Valley Wants to Cash In on Fasting

Like most of the health fads that catch on in Silicon Valley, this one broke through thanks to word-of-mouth—and a Medium post. Entrepreneur Sumaya Kazi extolled its virtues to 650,000 readers, while venture capitalist Phil Libin and others preached about it to anyone who would listen. Their miraculous idea was in fact a very old one: eating nothing at all for long stretches of time. Monthly Google searches for “intermittent fasting,” which has become a catchall term for various forms of the practice, have risen tenfold over the past three years, to as many as 1 million. That’s about as many as “weight loss” gets, and more than “diet.” Now comes the next step, as businesses try to turn various forms of the craze into profit.

The idea may sound troubling depending on your relationship with food, but paid-for fasting regimens are finding a new audience in the Valley, partly because they’re framed in terms of productivity, not only weight loss. (Fasting falls under the techy-sounding buzzword “biohacking,” like taking so-called smart pills or giving your brain tiny shocks.) There’s a growing body of research and anecdotal evidence showing a link between periods of noneating and increased focus and output, and perhaps even longer life. “Periods of nutrient restriction do good things,” says Peter Attia, whose medical practice focuses on the science of longevity. “The subjective benefits are evident pretty quickly, and once people do it, they realize—if this is going to give me any benefit in my performance, then it’s worth it.”

As part of a diabetes-prevention program, PlateJoy, a meal-plan subscription app, encourages users to fast to shed pounds and lessen their risk of developing the disease. The company wouldn’t say how many customers it has, but about 20 million people are eligible to get the $230-a-year coaching and progress-tracking program for free through their health insurer. (Insurers pay PlateJoy when their customers lose weight.) Co-founder Christina Bognet, a former health-care consultant and MIT-trained neuroscientist, says the plan encourages time-restricted feeding, in which practitioners eat only during a window of a few hours each day. Maintaining those restrictions, she says, has helped her keep off the 50 pounds she’s lost in recent years.

“We instruct our patients to jump right into it,” Bognet says. “We’re hearing from people who’ve said, ‘I have not been able to get my weight to budge, but now I’m down 7 pounds in two weeks.’ This is life-changing.” Five-year-old PlateJoy is profitable and looking to raise venture capital to supplement a smidgen of early funding from Y Combinator, 500 Startups, and other incubators.

Hvmn (pronounced “human”) pitches customers mostly on productivity and performance. Its chewable coffee cubes and other dietary supplements are supposed to enhance focus and cognitive function. One product contains synthetic versions of ketones, compounds your body creates when it’s fasting long enough to burn fat. Hvmn markets the drink to athletes ($99 for three small vials) as a way to boost performance and accelerate recovery. “It’s more efficient fuel for the brain and body,” says co-founder Geoffrey Woo, though he says they aren’t meant to replace the benefits of fasting.

Formerly known as Nootrobox, Hvmn has attracted more than $5 million in venture backing from the likes of former Yahoo! Chief Executive Officer Marissa Mayer and Zynga Inc. founder Mark Pincus. The technology behind its ketone drink lies in more than a decade of research into supplements for combat troops, work financed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Oxford.

Woo, who still fasts for 36 hours once a week, also helped start WeFast, a set of Facebook and Slack forums with thousands of members that began as a weekly breakfast for Hvmn employees. Members post advice and encouragement, track their progress, and link to the latest scientific research on fasting. “This will be considered just like exercise,” Woo says, adding that he expects fasting to become a multibillion-dollar industry. “Our problem is overconsumption, and that means reinstalling a new culture around eating.”

Valter Longo, a professor at the University of Southern California, has studied food restriction and longevity for decades. His research has shown that mice on fasting diets live longer and perform tasks better; that fasting in mice starves cancer cells and aids chemotherapy drugs; and that a very-low-calorie diet can slow multiple sclerosis by killing off bad cells and generating new ones. He advocates multiday fasting and sells a five-day, $250 diet package that he says mimics the effects of a fast. The box, called ProLon, includes soups, drink mixes, breakfast bars, vitamin supplements, and even desserts, but the portions are small enough that the customer will take in only about 1,100 calories on the first day and about 750 on each of the next four.

Since its introduction in 2016, more than 52,000 people have tried ProLon. Longo’s company, L-Nutra, is targeting about $12 million in revenue this year and estimates that sales will more than double next year. L-Nutra and the research behind it have received close to $60 million in grants and investment capital, including from the NIH, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and the U.S. Department of Defense. CEO Joseph Antoun says he’s aiming for reimbursement deals similar to PlateJoy’s with insurers and corporate wellness programs; he plans to take the company public within three years.

Even if you don’t remember the Valley’s last few health fads—Soylent, anyone?—there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of just how much these products are worth. Female rats on fasting diets have shown hormonal imbalances and ovary shrinkage. As for humans, there isn’t enough data on the long-term effects for doctors to reach a consensus. What is clear is that restricted-eating plans can make people more susceptible to anorexia nervosa and other disorders, says Lauren Smolar, director of programs at the National Eating Disorders Association.

“We consistently see cases where people have tried to control their intake of food, and it’s led to an eating disorder,” she says. “There ends up being this kind of reward feeling they’re going through, which triggers them to continue on this diet. And slowly this feeling of losing control, and not being able to know when to stop, can occur.”

Venture capitalist Libin, who lost 60 pounds fasting, acknowledges it isn’t for everyone. “It’s just something that works super well for me,” he says. “I have more energy, more stamina, more mental clarity. My mood is better—all of this stuff. And I’ve measured all of it.”

BOTTOM LINE – Startups focused on time-restricted feeding and low-calorie meal regimens plan to expand aggressively, but they may be a bit too far ahead of the science.

Private Colleges Dole Out Scholarships to Boost Enrollment, but It Isn’t Working

Private colleges have been aggressively discounting tuition in an effort to boost enrollment, a risky strategy that now may be backfiring as students aren’t signing up in droves, even at sale prices.

Tuition discount rates, or the share of gross tuition and fee revenue that schools shell out as grants and scholarships, increased to a record 49.9% for full-time freshmen at private colleges this academic year, according to a preliminary report by the National Association of College and University Business Officers. That is up from a then-record 48.2% in the 2016-17 school year.

Put simply, these schools bring in only about half of their published sticker price.

Overall tuition discount rates for undergraduates hit a record 44.8%, up from 43.2% last year, based on survey responses from 404 private schools. That figure is generally lower than it is for freshmen, as some schools front-load scholarship offers and others set flat per-year awards even as sticker prices increase.

Discount rates for schools with fewer than 4,000 students — institutions that are generally reliant on tuition dollars and for whom a small enrollment shift can hit hard — reached 51.7% this year for freshmen, and 46.1% overall.

Schools often use tuition discounts with the aim of boosting their academic profiles or luring more families to enroll. Even at a lower per-student price, if enrollment increases enough, the school’s net tuition revenue can grow.

That has been the case at Albion College in Albion, Mich. The school has a discount rate of around 70% — and slightly higher for freshmen — and just “a handful” of students pay full sticker price, says President Mauri Ditzler.

But with enrollment growing by 24% since 2014, to 1,568 total this year, the school is increasing its net tuition revenue. Dr. Ditzler also noted that even when students pay relatively little for tuition, the school still makes money on dorm rooms.

Albion may be an outlier, as enrollments at private, nonprofit schools nationwide have fallen for each of the last three years.

The financial impact of declining enrollment is being compounded now by the fact that schools are earning less from each student who does come to campus. On a per-student basis, net tuition revenue for freshmen fell by 0.1% this year at schools surveyed by NACUBO, the first decline since the 2011-12 academic year. Small schools reported a decline of 1.1%.

While there is no single number that indicates a tipping point to becoming unsustainable, said Ken Redd, senior director of research and policy analysis at NACUBO, “It’s becoming more and more of a strain on schools.”

Since private, nonprofit schools get more than a third of their total funding from net tuition revenue, the NACUBO report warned, continued declines in that pool of money “may limit institutions’ ability to fulfill their educational and public service missions.” The authors added, “The situation for small institutions appears even more precarious.”

The source of financial aid dollars is another cause for concern. Schools in the study reported that, on average, 10.7% of total undergraduate institutional aid was funded by endowments; there is no dedicated revenue source covering the rest.

At Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa., 17% of financial aid expenditures come from endowment funds.

“We have a long way to go,” said President John Bravman, explaining that he wants to fund more financial aid with endowment money, rather than from less predictable operating budgets. At the same time, the school is looking to increase its discount rate to around 37% from 31%, to compete with peers dangling discounts of their own.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)