He’d endured a sore throat and general malaise for a few days, believing it would get better, but that morning in August 2017, he knew that he had to do something about it.

“I was quite out of it,” said 27-year old Latuske, who was also due to go on vacation with his wife in just three days.

Short on time, he dreaded the idea of calling his local general practitioner only to wait days or even a week for an appointment, or to wait in a queue for an emergency appointment.

“I just needed to be seen without messing around with queues,” he said. “When you’re that ill, that’s the last thing you want to do.”

These days, this solution is somewhat easier, thanks to the internet.

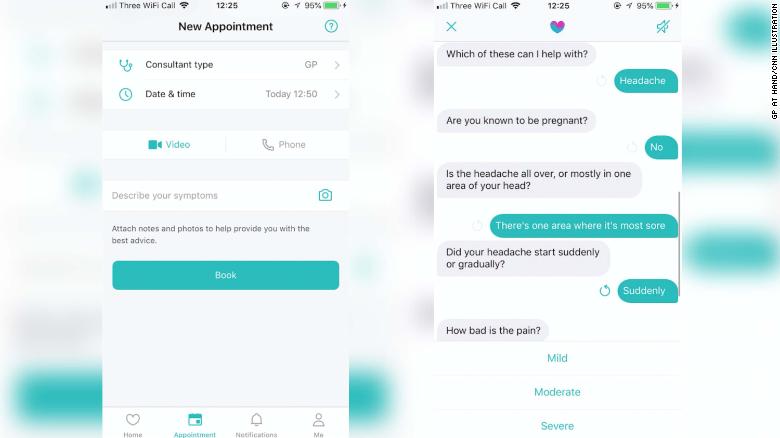

Latuske’s wife showed him a private medical app with which he could see a doctor within the hour — virtually. For a fee of £30 ($38), he could sign up, share his symptoms and video-call a doctor in the UK using the digital health provider

Push Doctor

“I was highly skeptical,” he said, adding that his instincts were to not trust such a service and question the credentials of doctors available through it. “But I was desperate.”

Within 20 minutes, he was speaking with a doctor, who soon diagnosed him with tonsillitis.

Within the hour, he was his nearest pharmacy, collecting prescriptions for antibiotics and pain relievers. And three days later, he was on vacation, as planned.

“I was impressed by the efficiency of the whole thing,” he said.

The service treated more than 1,000 different conditions last year, it says, with the majority of people getting the help they needed first time. “Patients have come to expect the same level of responsiveness from their health care services that they receive from online shops, TV providers and social network,” said Wais Shaifta, CEO of Push Doctor.

The app is one of many now available in the UK and worldwide to help people in need of medical attention who are unable to get to a doctor for various reasons, such as an overburdened practice, being too ill to move or being too remote to access one.

Some programs are even exploring the use of artificial intelligence to speed the process, quickly analyzing your symptoms to send you to the right expert. Experts in the field hope AI will also enhance the accuracy of diagnoses — more so than a real-life doctor.

The true test of AI

A recent study led by another online health service provider,

Babylon Health, found that when answering diagnostic questions typically found on a doctor’s exam in the UK, its AI technology diagnosed patients better than the doctors taking the test, with 81% accuracy compared with an average of 72% over the past five years among real-life doctors.

A subsequent test of the technology on clinical scenarios provided by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK looked at 100 independent symptom sets in need of diagnosis. Again, the AI achieved 80% accuracy, with the seven experts tested scoring between 64% and 94%.

The point of it all is efficiency, says Dr. Mobasher Butt, medical director at Babylon Health. The private app provides health care consultations for a small initial fee, but the company also powers the online service

GP at hand, which is provided for free in London through the country’s National Health Service.

“We have to find ways of helping our NHS service to be more efficient,” Butt said, adding that this use of AI can help patients get to the right services and help them manage long-term conditions, improve compliance with medication, give reminders and help with follow-ups and repeat prescriptions.

“When we start working smarter and using technology, you can see the great advantages that offers and frees up the time of doctors and nurses to do what they do best: to provide that human care to patients.”

A team at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London partnered with the Google company DeepMind came to a similar conclusion in a recent study in

Nature Medicine.

Their AI technology, designed to read eye scans and identify signs of disease, correctly identified over 50 eye diseases with 94% accuracy — matching the abilities of the world’s leading eye experts.

“The number of eye scans we’re performing is growing at a pace much faster than human experts are able to interpret them,” Dr. Pearse Keane, a consultant ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust who led the research, said

in a statement. “The AI technology we’re developing is designed to prioritize patients who need to be seen and treated urgently by a doctor or eye care professional. If we can diagnose and treat eye conditions early, it gives us the best chance of saving people’s sight.”

Next, this research will undergo clinical trials to see how the technology might improve patient care in practice.

But professional organizations like the Royal College of Physicians want to ensure that the value of a real-life physician is not lost as technology continues to evolve.

“AI to support patient care is being developed in a variety of ways and has huge potential to support doctors and enable them to spend more time with patients,” Jane Dacre, the group’s president and a professor of medical education at University College London, said in a statement. “Although this technology is exciting, the physician still holds the crucial role of the oversight of the vital human and caring side of medicine — an aspect of care that cannot be underestimated.”

She stressed that despite the positive results of recent studies, AI cannot yet replace a fully trained doctor.

“We need much more robust trials and evidence to work out how it can best be used. We need studies in real patients, in real time, in the real NHS,” she said.

The value of relationships

Among all these changes and improvements in time, accuracy and efficiency, experts are concerned that another crucial aspect of health care is being forgotten: continuity of care, an ongoing relationship with a particular doctor or health care provider who knows your history and knows you.

On that front, “the trend is going in the wrong way,” said Dr. Denis Pereira Gray, a former family physician and professor emeritus at the University of Exeter in the UK.

This is down to the fact that the UK, compared with other European countries, is seriously short on doctors, and continuity is not valued by policymakers, he said.

But in

a recent study, Pereira Gray found that seeing the same doctor can in fact save lives, with those seeing the same physician over time having lower death rates based on a review of 22 studies across nine countries. Eighteen of the studies, 82%, found that repeated contact with the same doctor meant fewer deaths.

In some studies, the effect doubled, he added.

The review also found that this benefit applies beyond family physicians, extending to specialists in general medicine, surgery and psychiatry, according to Pereira Gray, who noted this outcome across countries, cultures, languages and health systems. “This is much more likely to indicate a serious human effect,” he said.

“Patients have long known that it matters which doctor they see and how well they can communicate with them,” Pereira Gray said. “Until now, arranging for patients to see the doctor of their choice has been considered a matter of convenience or courtesy; now, it is clear it is about the quality of medical practice and is literally ‘a matter of life and death.’ “

Research has also shown that continuity of care results in patients being more satisfied, significantly more likely to follow medical advice and much more likely to take up personal protective care, like immunizations or cancer screening, Pereira Gray said. They also show more efficient use of hospitals and a reduced likelihood of using emergency departments.

“All of those are advantages, as well as [avoiding] death,” he said.

And it’s not just long-term relationships. Short-term ones are just as beneficial, according to Pereira Gray. For example, in one study in the United States, mortality was greater among people who were readmitted to the same hospital after colorectal surgery but saw a different medical team, he said.

“Sheer familiarity with a doctor reduces anxiety,” he added. “And patients are more likely to disclose important information that can sometimes be sensitive and embarrassing.”

Alongside that, the more doctors get to know patients, they become more responsive to them as individuals. “Trust goes up in the patient, and the doctors become more sensitive to the patient,” Pereira Gray said.

“People talk more freely to people they trust and know.”

Is seeing the same doctor ‘outdated’?

Is familiarity or technological efficiency better for our health in the long run? Butt believes that the idea of seeing the same general practitioner for life “is now outdated” but argues that good care needn’t be an either-or situation.

“We’re not trying to replace doctors,” Butt said. It’s not “man vs. machine.”

Instead, he says the future is about humans working with machines, adding that with his health care app, users can request to speak to the same doctor they have previously.

“Continuity of care is important, and where it’s needed, we offer that,” Butt said, giving the example of mental health care. But he also highlighted that many practices today do not enable patients to see the same doctor, due to limited staff and the use of temporary or substitute doctors. “It’s just not the reality in most cases.”

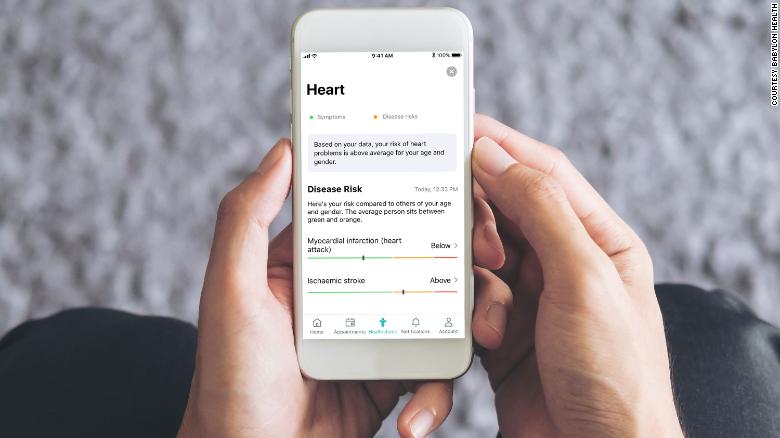

More than 200 doctors provide their services to Babylon Health, Butt said, and he hopes to make the technology more sophisticated and interactive, for example by using a phone’s microphone to help doctors listen to a patient’s chest remotely. A physical health check service is also now available, with people inputting information about their current health and diet to see how they’re doing in general and what lifestyle factors they could improve to “prevent some diseases from happening,” he said.

Eighty-five percent of issues can be dealt with via a video call, Butt added, with more serious issues or blood tests needing an in-person appointment, which is then obtained through the patient’s NHS practice or a private physician.

“What’s important is continuity of the medical record, so any clinician involved in that person’s care can pick it up,” Butt said.

Pereira Gray agrees that it needn’t be a tradeoff. “I don’t think technology and personal care are in opposition. They should complement each other,” he said, but he feels that with remote consultations, social determinants of health are less accounted for, such as a person’s environment, poverty level, family or work.

“All of that feeds into the sort of illnesses that people get,” he said. “If you’re talking about a doctor doing a quick-fix consultation, it’s very much less likely that will be unraveled or understood.”

But he admits that certain conditions are quick and simple and that any doctor anywhere can handle those quickly and simply, to Butt’s point.

The current selling point for the use of technology is access, Butt believes, either where in-person appointments are limited or where mobility is an issue — both among the frail and elderly or in low-income countries where communities can be miles from the nearest health care center with no means of transport.

The Babylon team is providing mobile health services in Rwanda as well as the UK, with plans to extend to other countries on the African continent, as well as North America and the Middle East.

According to Push Doctor, the need for remote access is in high demand among middle-age and older people in countries like the UK. “It’s not just millennials who are embracing [these] platforms,” Shaifta said. “Research shows that digital health has universal appeal, with high demand from over-45s citing an increased need for remote services and the convenience they bring.”

For now, which option is ultimately better for your health? The results just aren’t in yet.