As always, the Keynote Address is always a highly anticipated talk GU

ASCO, and this year Dr. David Penson from Vanderbilt University

provided an overview of financial toxicity and quality of among oncology

patients.

Dr. Penson started by highlighting the goals of any new treatment for

cancer, as quoted from Dr. Ian Tannock: We want the patient to live

longer and better, and in the end what matters to patients is overall

survival and quality of life. Defining quality of life is challenging as

there are numerous definitions available in the literature but none

that do a great job of capturing the concept. The National Cancer

Institute’s definition of quality of life is “the overall enjoyment of

life” – not exactly easy to measure. A relevant model to help define

health-related quality of life is provided by Dr. Penson in the

following figure:

The taxonomy of financial hardship in cancer is comprised of three arenas:

- Material conditions: for example, out-of-pocket expenses, missed work, reduced/lost income, and medical debt/bankruptcy

- Psychological response: for example, feeling of distress due to

costs of cancer care, and concern about wages/income meeting expenses

related to costs of cancer care

- Coping behaviors: for example, taking less of or skipping medication or delaying or missing a physician visit

Dr. Penson’s goals for his presentation are to (i) introduce the

concept of financial toxicity in cancer therapy and make people aware of

the negative impact this has on all patient-centered outcomes, and (ii)

to review the financial toxicity of common GU malignancies. He hopes

that we will be aware of the negative effects of financial toxicity of

our therapies on quality of life, and that this will generate a desire

to start a discussion with our patients around the cost of treatment and

a willingness to understand their non-clinical financial situation.

Furthermore, he hopes we think twice before ordering costly

interventions which may have little impact on clinical course but large

impact on the patient’s finances and quality of life.

The scope of the financial burden is that out-of-pocket costs are a

side effect of medical care. In a study of data from the 2011 National

Cancer for Health Statistics, Americans <65 years of age noted that

40-50% had financial burden from medical care, and was still 20-25% in

those ≥65 years of age.

1 Specific to financial toxicity of

cancer survivors, data from the 2013-2016 National Health Interview

Survey suggests that 16-27% of patients have problems paying their

medical bills, 44-52% are worried about paying medical bills, and 9-14%

delayed medical care secondary to financial worries. In Dr. Penson’s

opinion, these data are only going to get worse.

When looking further at the median monthly out of pocket expenses,

Dr. Penson highlighted a 2013 pilot study assessing the financial

toxicity of cancer treatment.

2 Among 254 participants, Zafar

et al. conducted baseline and follow-up surveys regarding the impact of

health care costs on well-being and treatment among cancer patients who

contacted a national copayment assistance foundation along with a

comparison sample of patients treated at an academic medical center.

There were 75% of patients that applied for drug copayment assistance.

Forty-two percent of participants reported a significant or catastrophic

subjective financial burden, 68% cut back on leisure activities, 46%

reduced spending on food and clothing, and 46% used savings to defray

out-of-pocket expenses. Shockingly, to save money, 20% took less than

the prescribed amount of medication, 19% partially filled prescriptions,

and 24% avoided filling prescriptions altogether. Annual out-of-pocket

costs do not fare much better. Among 1,409 Medicare beneficiaries

(median age, 73 years [IQR 69-79 years]; 46.4% female and 53.6% male)

diagnosed with cancer, the type of supplementary insurance was

significantly associated with mean annual out-of-pocket costs incurred

after cancer diagnosis:

3

- $2116 among those insured by Medicaid

- $2367 among those insured by the Veterans Health Administration

- $5976 among those insured by a Medicare health maintenance organization

- $5492 among those with employer-sponsored insurance

- $5670 among those with Medigap insurance coverage

- $8115 among those insured by traditional fee-for-service Medicare but without supplemental insurance coverage

For Medicare beneficiaries, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will close

the Part D coverage gap (doughnut hole), which will reduce cost sharing

from 100% in 2010 to 25% in 2020 for drug spending above $2,960 until

the beneficiary reaches $4,700 in out-of-pocket spending. To assess this

impact, Dusetzina and Keathing

4 used the Medicare July 2014

Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing

Information Files from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

for 1,114 stand-alone and 2,230 Medicare Advantage prescription drug

formularies. The average price per month for included medications was

$10,060 (range, $5,123 to $16,093). In 2010, median beneficiary annual

out-of-pocket costs for a typical treatment duration was $12,160 (IQR

$12,102 to $12,262) for sunitinib. With the assumption that prices

remain stable after the doughnut hole closes, beneficiaries will spend

approximately $2,550 less. As such, out-of-pocket costs for Medicare

beneficiaries taking orally administered anticancer medications are high

and will remain so after the doughnut hole closes.

According to data from UNC Chapel Hill, financial toxicity is a

possible cause of poor compliance. In a study of 134 bladder cancer

patients, 33 (24%) endorsed financial toxicity (defined as “to pay more

for medical care than you can afford”). Participants who were younger (p

= 0.02), black (p = 0.01), reported less than a college degree (p =

0.01) and had noninvasive disease (p = 0.04) were more likely to

report financial toxicity.

5 Patients who

endorsed financial toxicity were more likely to report delaying care

(39% vs 23%, p = 0.07) due to the inability to take time off work or

afford general expenses. Furthermore, those

with financial toxicity reported worse physical and mental health (p =

0.03 and <0.01, respectively), and lower cancer specific health

related quality of life (p = 0.01), physical well-being (p = 0.01) and

functional well-being (p = 0.05). In a study looking at the impact of

cancer on a patient’s net worth and debt, Gilligan et al.

6

assessed 9.5 million estimated new diagnoses of cancer from 2000-2012.

At two years after diagnosis, 42.4% depleted their entire life’s assets,

with higher adjusted odds associated with worsening cancer, requirement

of continued treatment, demographic and socioeconomic factors (ie,

female, Medicaid, uninsured, retired, increasing age, income, and

household size), and clinical characteristics (ie, current smoker, worse

self-reported health, hypertension, diabetes, lung disease). The

average losses were $92,098. At four years past diagnosis, financial

insolvency extended to 38.2%, with several consistent socioeconomic,

cancer-related, and clinical characteristics remaining significant

predictors of complete asset depletion.

Financial toxicity also affects general quality of life. Data from

the 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey suggested that among 19.6

million cancer survivors (1,329 patients completed the survey), 28.7%

reported at least one financial problem.

7 Furthermore, 7.6%

borrowed money, 11.5% could not afford to cover the cost of medical care

visits, and 20.9% worried about paying their medical bills. Financial

toxicity is also associated with worse survival. Looking at data from

the Western Washington SEER registry (1995-2009) linked to federal

bankruptcy records, patients who filed for bankruptcy were more likely

to be younger, female, and nonwhite, to have local- or regional- (vs

distant-) stage disease at diagnosis, and have received treatment.

8

After propensity score matching, 3,841 patients remained in each group

(bankruptcy v no bankruptcy). The adjusted hazard ratio for mortality

among patients with cancer who filed for bankruptcy versus those who did

not was 1.79 (95% CI, 1.64-1.96). Hazard ratios varied by cancer type,

including colorectal, prostate, and thyroid cancers with the highest

hazard ratios. Importantly, excluding patients with distant-stage

disease from the models did not have an effect on results.

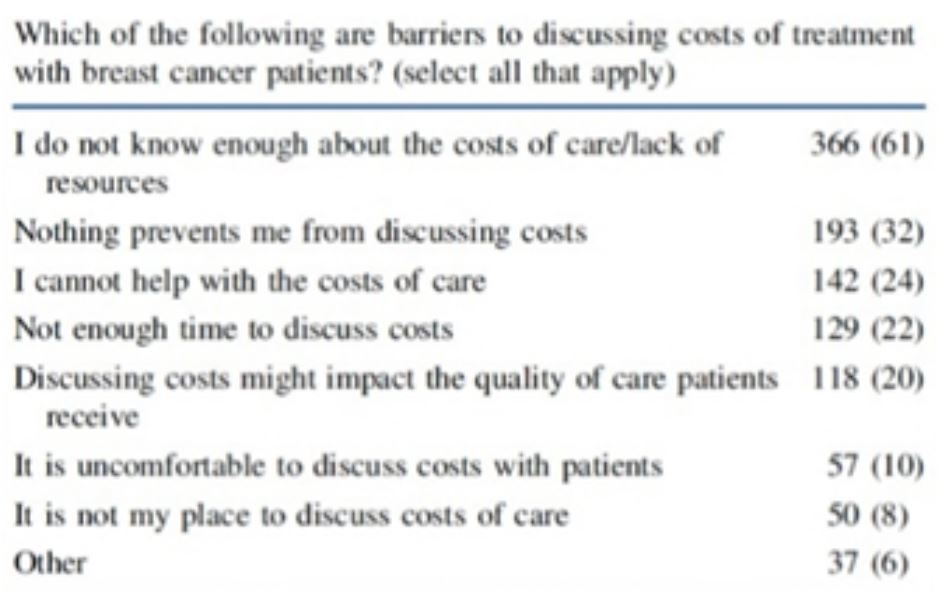

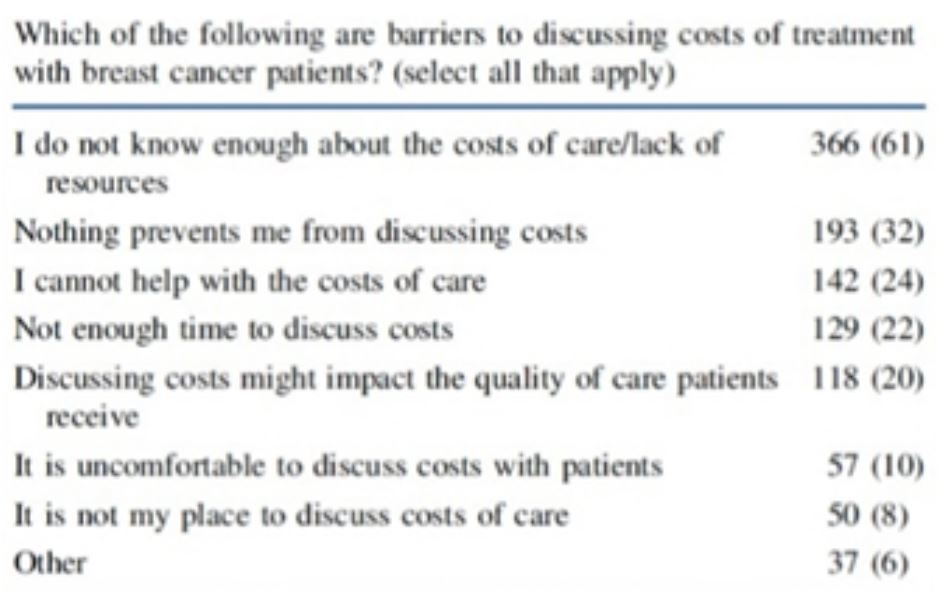

According to Dr. Penson, we have an opportunity to communicate costs

to our patients. Looking at the breast cancer literature, 2,293 members

of the American Society of Breast Surgeons were surveyed, with a 25%

response rate [9]. Shockingly, only 6% of providers included

out-of-pocket costs among the top three most influential factors in

clinical decision making. As follows is the reasons for why providers

were hesitant to discuss the impact of out-of-pocket cost:

Summarizing the financial toxicity among all cancer patients, Dr. Penson highlighted the following points:

- The scope of the problem is greater than many providers appreciate

- Patients cope by avoiding necessary care to save money, and/or going into debt

- Financial toxicity has a negative impact on other clinical outcomes

- Cost communication is not routinely part of the doctor-patient interaction

- We need to start by: acknowledging the problem, learning more about

costs so we can inform our patients, begin a discussion of financial

toxicity with patients, and include financial toxicity as a potential

adverse event in future studies and in shared decision-making

discussions.

Dr. Penson then discussed the highlighted each of prostate, bladder

and kidney cancer and the impact of financial toxicity, starting with

prostate cancer. A study from 2010 assessed out-of-pocket costs among

512 patients newly diagnosed with prostate cancer and undergoing either

radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy.

10 Participants

completed self-reported generic and prostate-specific HRQoL and

indirect-cost surveys at baseline and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months

follow-up. Total mean out-of-pocket costs varied between radical

prostatectomy and EBRT groups at 3-month ($5576 vs. $2010), 6-month

($1776 vs. $2133), 12-month ($757 vs. $774), and at 24-month follow-up

($458 vs. $871). Linear mixed models indicated that radical

prostatectomy was associated with lower medication costs (OR 0.61, CI

0.48-0.89) and total out-of-pocket costs (OR 0.71, CI 0.64-0.92).

Prostate-specific HRQoL items of urinary function (OR 0.72; adjusted-CI =

0.58-0.84), bowel function (OR 0.96; adjusted-CI = 0.78-0.98), sexual

function (OR 0.85; adjusted-CI = 0.72-0.92), urinary bother (OR 0.79;

adjusted-CI = 0.67-0.83), and sexual bother (OR 0.88; adjusted-CI =

0.76-0.93) were inversely related to out-of-pocket costs. Surgical

approach may be a way to temper cost, as robotic prostatectomy has been

associated with a $138 decreased out of pocket cost to the patient

compared to open radical prostatectomy. Importantly, this is not a

problem among prostate cancer patients unique to the United States: both

Australia and Canada have reported financial toxicity among prostate

cancer patients.

Indeed, bladder cancer is an expensive disease to treat, with an

annual cost of nearly $4 billion per year, however little is known about

the financial toxicity among bladder cancer patients. As mentioned

earlier in the talk, the UNC study

5 showed that 24% of

patients endorsed financial toxicity (defined as “to pay more for

medical care than you can afford”). Participants who were younger (p =

0.02), black (p = 0.01), reported less than a college degree (p = 0.01)

and had noninvasive disease (p = 0.04) were more likely to

report financial toxicity. Beyond this one study, Dr. Penson notes that

there are no other studies assessing financial toxicity in this

expensive, complex, morbid disease.

According to Dr. Penson, kidney cancer financial toxicity is all

about the drugs. Over the past two decades, there has been an explosion

of new therapies for renal cell carcinoma. These drugs have inherently

changed the way we approach the disease and have resulted in benefit in

terms of prolonging survival. These agents, however, are quite costly

with annual wholesale costs of these agents ranging from $75,000 to

$200,000 per year. The risk of financial toxicity in this setting is

considerable and often not considered in medical decision making. While

other components in healthcare will contribute to financial toxicity,

Dr. Penson believes that the drugs are the key drivers here. A study

from 2015 assessed the associated costs for mRCC in the US using the

LifeLink Health Plan Claims Database.

11 A total of 1,527 mRCC

patients were analyzed; in 2010, nine unique treatment regimens were

used for first-line treatment, 8 for second-line treatment, and 8 for

third-line treatment. For 767 patients receiving modern therapy who were

< 65 years old, and stratifying by whether the first-line treatment

was oral or intravenous, drug cost per patient with ancillary services

was $59,664 versus $86,518, respectively (p = 0.001). Total costs and

drug out-of-pocket costs per patient during the first year increased by

the number of medication switches: $111,680 to $2355 for no switches,

$149,994 to $2538 for 1 switch, and $196,706 to $3524 for 2 or more

switches. Impressively, in 2004 the median drug cost was $11,458, while

by 2010 it rose to $68,660.

Dr. Penson concluded this talk on financial toxicity with the following summary points:

- Financial toxicity should be considered an adverse event of therapy, similar to other side effects of treatment

- This patient-centered endpoint can have a profound effect on our patient’s quality of life and daily existence

- While perhaps not completely avoidable, financial toxicity and its effect on our patients must be minimized

How can we help minimize financial toxicity?

- Discuss it upfront with our patients, creating an environment where

it is acceptable to talk about it. If you don’t know the specifics,

identify someone in your institution that dose

- Treat financial toxicity as another possible side effect when undertaking shared-decision making

- Think about the financial impact on the patient before you – do not

order discretionary testing or follow-ups that may not change

management, and do not initiate therapies that may have little or no

proven clinical benefit to the patient

- Consider the cost to the patient when choosing medical therapy for GU cancers

Presented by: David Penson, MD, MPH, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee

Written By: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Assistant Professor of

Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of

Georgia @zklaassen_md

at the 2020 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, ASCO GU #GU20, February 13-15, 2020, San Francisco, California

References:

1. Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket

costs as side effects. N Engl J Med 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1484-1486.

2. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of

cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the

insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist 2013;18(4):381-390.

3. Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket Spending and Financial Burden

Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017 Jun

1;3(6):757-765.

4. Dusetzina SB, Keating NL. Mind the Gap: Why closing the Doughnut Hole

is Insufficient for Increasing Medicare Beneficiary Access to Oral

Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2016 Feb 1;34(4):375-380.

5. Casilla-Lennon MM, Choi SK, Deal AM, et al. Financial toxicity among

patients with bladder cancer: Reasons for Delay in Care and Effect on

Quality of Life. J Urol 2018 May;199(5):1166-1173.

6. Gilligan AM, Alberts DS, Roe DJ, et al. Death or Debt? National

Estimates of Financial Toxicity in Persons with Newly-Diagnosed Cancer.

Am J Med 2018 Oct;131(10):1187-1199.

7. Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care

and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life

among US cancer survivors. Cancer 2016 Apr 15;122(8):283-289.

8.

Ramsey

SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk

Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016

Mar 20;34(9): 980-986.

9. Greenup RA, Rushing CN, Fish LJ, et al. Perspectives on the costs of

cancer care: A Survey of the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann

Surg Oncol 2019 Oct;26(10):3141-3151.

10. Jayadevappa R, Schwartz JS, Chhatre S, et al. The burden of

out-of-pocket and indirect costs of prostate cancer. Prostate 2010

Aug;70(11):1255-1264.

11.

Geynisman

DM, Hu JC, Liu L, et al. Treatment patterns and costs for metastatic

renal cell carcinoma patients with private insurance. Clin Genitourin

Cancer 2015 Apr;13(2):e93-100.

https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-gu-2020/asco-gu-2020-bladder-cancer/119188-asco-gu-2020-financial-toxicity-and-quality-of-life-understanding-and-improving-patient-centered-outcomes-in-genitourinary-malignancies.html