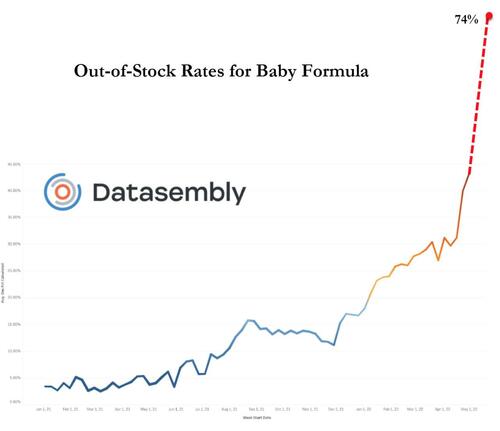

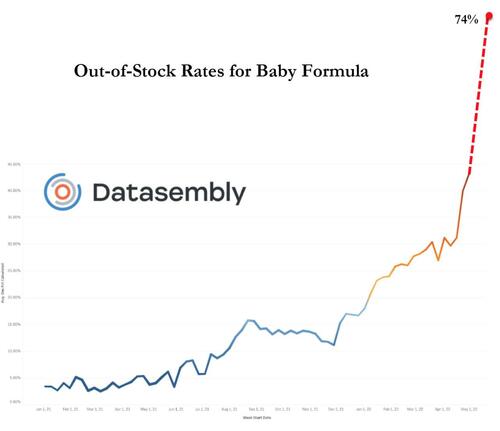

Despite all the bluster from The White House on its actions to relieve the crisis, the baby formula shortage continued to worsen last week.

Earlier this week, President Biden crowed on Twitter at the actions he has taken to 'fix' the problem:

Even more stunningly, ten states now have shortage rates at 90% or greater, with Georgia hardest hit at 94%.

So since the president was made aware of shortages, the crisis has only worsened, but then again, haven't we seen the same thing again and again (Afghanistan, gas prices...)

As Philip Wegmann detailed earlier via RealClear Politics, the Biden presidency was born from crisis. And that was by design.

The country was looking for stability during the chaos of COVID-19, and the former vice president offered a shaken electorate the promise of tested leadership and trusted experience. At the very least, Biden said he could offer an improvement over the reality television politics that had defined his opponent’s time in office. And that pitch worked. He won the White House, but more crises followed.

A land war in Europe, a persistent pandemic, an ugly end to the war in Afghanistan, and an unrelenting cycle of historic inflation: Each challenge came so quickly, compounding and cascading over the last, that White House staffers reportedly joked that a plague of locusts must be next. Instead, it was baby formula.

They didn’t expect a nationwide shortage, and neither did the president. “I don’t think anyone anticipated the impact of the shutdown of one facility – the Abbott facility,” Biden told reporters Wednesday, referring to the Abbott Laboratories Inc. plant in Michigan that went offline in February due to safety concerns and that has led to months-long scarcity.

But baby formula manufacturers did anticipate the impact three months ago, and moments before Biden started fielding questions from the press, they had just said as much in front of the cameras. Robert Cleveland, senior vice president for North American operations of the Reckitt Co., was the first of the manufacturers to speak, and he said he told Biden that “we knew from the very beginning this would be a very serious event.”

Tarun Malkani, president and CEO of Gerber, told Biden that his company might be a relatively small player in powdered formula but they were doing all they could out of a sense of “national duty.” He added that they were operating with the same level of urgency today that they did “when I got that first phone call informing me of the crisis situation.”

Murray Kessler, CEO of Perrigo Company, told Biden that as soon as his company heard about the recall “we could foresee that this was going to create a tremendous shortage.”

The other manufacturers present said the same, and yet the president admitted he wasn’t made aware of the gravity of the crisis until last month. Hadn’t those CEOs just told him they understood it would have a very big impact the moment the Abbott plant was shuttered, a reporter asked.

“They did,” Biden replied, “but I didn’t.”

That terse admission undercut the official administration line. The White House has insisted for weeks that they were quick to react and that they mounted a “whole-of-government approach” since the Food and Drug Administration issued the recall on February 17. Apparently, and at least according to Biden himself, this did not include the president until April.

Although late to comprehend the crisis, the months-long absence did not prevent Biden from telling families without baby food that he felt their pain. “There is nothing more stressful than the feeling like you can’t get what your child needs,” he said. “As a father and grandfather,” he added, “I understand how difficult this shortage has been.”

That empathy did not satisfy the press corps. Reporter after reporter pressed White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre with various iterations of the same question: What did the president know about the formula shortage and when did he know it? Jean-Pierre reiterated that the administration had taken a whole-of-government approach. “We’ve been working on this for months,” she insisted. “We’ve been taking this incredibly seriously.”

She said that the day after the Abbott plant went dark, the U.S. Department of Agriculture was cutting red tape to allow states more flexibility to purchase formula. And to get that plant back up and running safely, scientists at the FDA, she added, “have been working around the clock.”

It wasn’t until May though, three months after Abbott went dark and the industry began racing to meet demand, that Biden invoked the Defense Production Act. Store shelves were bare across the country by the time the president finally launched Operation Fly Formula to bring baby food into domestic markets from overseas.

But when did the White House get a call alerting the administration that perhaps the issue required presidential involvement? “I don’t have the timeline on that,” Jean-Pierre replied. “All I can tell you as a whole-of-government approach, we have been working on this since the recall in February.”

Another reporter asked a little later if the White House could detail the early steps that were taken: meetings or phone calls, for instance, or briefings back in February when the shortage first began. “I don't have that information,” the press secretary answered, promising to make that material public when it became available.

Was the White House spokeswoman calling into question the April date that Biden had just given, a third reporter asked. Had he misspoken? “No,” Jean-Pierre pushed back, “I am not questioning the president at all.” She hadn’t talked with the president on this topic, she said, before coming to brief the press.

Biden predicted earlier in the day that it would take “a couple more months” before supply returned to normal. Fully stocked shelves can’t come soon enough for families with newborns or for individuals with metabolic disorders who rely on special formulas that only Abbott manufactures. Nationwide, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis, 23% of powdered formula was out of stock last week. Another 11% was entirely out of stock, the paper reported, because of supply-chain shortages and inflation.

Other manufacturers besides Abbott, including those speaking at the White House Wednesday, have ramped up manufacturing to meet demand. Domestic production, Jean-Pierre told reporters, “has even increased from last year.” Eventually, the shortages will end. A larger question remains, though, one that gets to the central promise that Biden made during his campaign: How serious does an issue have to be before it is brought to the president's attention?

The press secretary ran through the timeline again as she had before, telling RealClearPolitics that “we did everything that we can to cut red tape, and now the Defense Production Act, flying in the formula from abroad. All of those things were actions we took to deal with this crisis.”

She did not answer the general question with any specificity other than to say, “There are always multiple crises happening that we are dealing with all at once.”

https://www.zerohedge.com/political/biden-admits-he-was-awol-until-april-baby-formula-crisis