The shooting that killed three people and injured another at a Greenwood, Indiana, mall on July 17 drew broad national attention because of how it ended – when 22-year-old Elisjsha Dicken, carrying a licensed handgun, fatally shot the attacker.

While Dicken was praised for his courage and skill – squeezing off his first shot 15 seconds after the attack began, from a distance of 40 yards – much of the news coverage drew from FBI-approved statistics to assert that armed citizens almost never stop such attackers: “Rare in US for an active shooter to be stopped by bystander” (Associated Press); “Rampage in Indiana a rare instance of armed civilian ending mass shooting” (Washington Post); and “After Indiana mall shooting, one hero but no lasting solution to gun violence” (New York Times).

Evidence compiled by the organization I run, the Crime Prevention Research Center, and others suggest that the FBI undercounts by an order of more than three the number of instances in which armed citizens have thwarted such attacks, saving untold numbers of lives. Although those many news stories about the Greenwood shooting also suggested that the defensive use of guns might endanger others, there is no evidence that these acts have harmed innocent victims.

“So much of our public understanding of this issue is malformed by this single agency,” notes Theo Wold, former acting assistant attorney general in the U.S. Department of Justice. "When the Bureau gets it so systematically – and persistently – wrong, the cascading effect is incredibly deleterious. The FBI exerts considerable influence over state and local law enforcement and policymakers at all levels of government.”

As many on the left seek more limits on gun ownership and use in response to mass shootings and the uptick in violent crime, and many on the right seek greater access to firearms for protection, the media’s reliance on incomplete statistics in covering incidents such as the one at the Greenwood Park Mall takes on new significance.

The FBI defines active shooter incidents as those in which an individual actively engages in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated, public area. But it does not include those it deems related to other criminal activity, such as a robbery or fighting over drug turf.

The Bureau reports that only 11 of the 252 active shooter incidents it identified for the period 2014-2021 were stopped by an armed citizen. An analysis by my organization identified a total of 281 active shooter incidents during that same period and found that 41 of them were stopped by an armed citizen.

That is, the FBI reported that 4.4% of active shooter incidents were thwarted by armed citizens, while the CPRC found 14.6%.

Two factors explain this discrepancy – one, misclassified shootings; and two, overlooked incidents. Regarding the former, the CPRC determined that the FBI reports had misclassified five shootings: In two incidents the Bureau notes in its detailed write-up that citizens possessing valid firearms permits confronted the shooters and caused them to flee the scene. However, these cases were not listed as being stopped by armed citizens because the attackers were later apprehended by police. In two other incidents the FBI misidentified armed civilians as armed security personnel. In one incident, the FBI simply failed to mention the citizen engagement at all.

For example, the Bureau’s report about the Dec. 29, 2019 attack on the West Freeway Church of Christ in White Settlement, Texas, that left two men dead does not list this as an incident of “civic engagement” because the perpetrator was fatally shot by a parishioner who had volunteered to provide security during worship. That man, Jack Wilson, told RealClearInvestigations he was not a security professional. He said that 19 to 20 members of the congregation were armed that day, and they didn’t even keep track of who was carrying a concealed weapon.

As for the second factor -- overlooked cases -- the FBI, more significantly, missed an additional 25 incidents identified by CPRC in which the active shooters were thwarted by armed civilians (see full list here). These include:

- An August 31, 2021, incident in Syracuse, New York, in which a property manager pulled out a legally possessed 9mm handgun and fatally wounded a man who opened fire on a crowd outside a building. The district attorney credited the property manager with saving the lives of several individuals.

- An August 11, 2021 incident in San Antonio, Texas, in which a woman who crashed into a parked car in San Antonio’s West Side neighborhood climbed out of her vehicle and began shooting indiscriminately at people who came out of their homes to rush to her aid. An armed resident fired back and shot the driver to death.

- A February 13, 2019 incident in Colonial Heights, Tennessee, in which a man, after killing his wife, turned his gun on others in dental office where she worked. A patient who had a concealed handgun permit holder shot the murderer as he was aiming at another person.

These omissions and discrepancies are not surprising given the limits of data collection and the judgment calls involved in categorizing such incidents. Law enforcement agencies around the country do not provide comprehensive reports of active shooter incidents, so local news coverage is a crucial source of information. The FBI contracts out this work to the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center at Texas State University and then reviews and refines its findings.

The CPRC discovered cases the Center missed, but even the CPRC’s approach almost certainly misses incidents. “[T]here’s no reason to think that the [CPRC’s] list is complete, since there may well have been such incidents that weren’t covered in the news in a way that would come up on the Center’s searches,” UCLA Law Professor Eugene Volokh wrote in June.

Asked about these discrepancies, the FBI declined to address them. A representative from the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center, M. Hunter Martindale, suggested that its numbers were not definitive:

We do appreciate you sending potential active shooter cases for the FBI team to review for inclusion in the active shooter dataset. As promised, I sent the email chain to the FBI team yesterday. As I’m sure you know, the FBI Active Shooter reports are released on an annual basis. My assumption is that any amendment retroactively adding cases would likely be included in a release with the annual report.

Although collecting such data is fraught with challenges, some see a pattern of distortion in the FBI numbers because the errors almost exclusively go one way, minimizing the life-saving actions of armed citizens.

“Whether deliberately through bias or just incompetence, the FBI database of active shooters cannot be trusted,” said Gary Mauser, an emeritus professor at Simon Fraser University in Canada who has extensively studied gun control and defensive gun uses. Mauser’s concern dovetails with those voiced by Rep. Jim Jordan in a July 27 letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray. Jordan alleged that whistleblowers have come forward claiming political biases in the FBI’s domestic terrorism data.

Despite these problems, the FBI’s numbers are routinely cited as authoritative by the news media. In its coverage of the Greenwood mall attack, the Washington Post linked to a Bureau report while informing readers, “In recent studies of more than 430 ‘active shooter incidents’ dating back to 2000, the FBI found that civilians killed gunmen in just 10 cases.”

In its Greenwood article, the Associated Press reported, “From 2000 to 2021, fewer than 3% of 433 active attacks in the U.S. ended with a civilian firing back, according to the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center at Texas State University.”

When my organization emailed Ed White, the AP reporter who wrote that article, about omissions in the Texas State numbers, he responded: “Our reporting, citing the specific research by Texas State U. over a 20-year period, was accurate. No correction was necessary.”

News outlets often raise concerns that allowing concealed handgun carry will result in innocent bystanders being shot or in police accidentally shooting permit holders. White’s AP dispatch on the Greenwood shooting quoted Adam Lankford, identified as “a criminal justice expert at the University of Alabama,” who stated: "While it’s certainly a good thing in this mall shooting that someone was able to stop it before it went any further, let’s not think we can substitute that outcome in all past and future incidents. If everyone’s carrying a firearm, the risk that something bad happens just gets much larger."

Carl Moody, a professor at William & Mary who studies mass public shootings, told RCI that such warnings are misleading:

The media and gun control advocates always seem concerned with the worst possible outcomes when firearms are involved. We know that armed citizens do, in fact, stop active shooters. And while there’s a possibility of a bystander getting hurt, the data show that an armed citizen has yet to accidentally shoot an innocent bystander. We also know that the police have accidentally shot the hero citizen just once. That was in Colorado on June 21, 2021. That’s not something that would normally happen, because the police usually arrive long after the incident is resolved.

Experts interviewed by the Washington Post and New York Times argue that stopping these attacks should be left to the police. “I think you might get more individuals carrying, sort of primed for something to happen, which is particularly dangerous … in reality that’s the job of the police,” Indiana University Bloomington law professor Jody Madeira told the Washington Post.

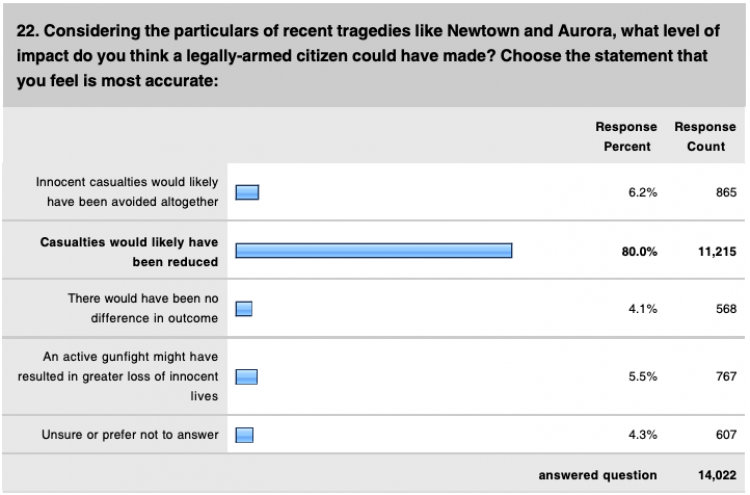

But many in law enforcement disagree. In March 2013, PoliceOne surveyed its 380,000 active-duty and 70,000 retired law enforcement officer members. Eighty-six percent of members believed that casualties from mass public school shootings could be reduced or “avoided altogether” if citizens had carried permitted concealed handguns in those places. Seventy-seven percent supported “arming teachers and/or school administrators who volunteer to carry at their school.” No other policy to protect children and school staff had such widespread support.

“A deputy in uniform has an extremely difficult job in stopping these attacks,” Sarasota County, Florida, Sheriff Kurt Hoffman told RCI. “These terrorists have huge strategic advantages in determining the time and place of attacks. They can wait for a deputy to leave the area, or pick an undefended location. Even when police or deputies are in the right place at the right time, those in uniform who can be readily identified as guards may as well be holding up neon signs saying, ‘Shoot me first.’ My deputies know that we cannot be everywhere.”

Similarly, Massad Ayoob, a self-defense advocate who has taught police techniques to law enforcement since 1974, noted: “When a life-threatening crisis strikes and seconds count, the real first responders are the citizens present.”

The FBI’s active shooting reports do not mention whether the attacks occur in gun-free zones. “The issue is that when places are posted as gun-free zones, law-abiding citizens obey those rules and would be unable to stop the attacks in those areas,” notes Professor Moody.

Surveys show that criminologists and economists had the same top four preferred policies for stopping mass public shootings. On a 1 to 10 scale where 1 was the least effective policy and 10 the most, American criminologists rated the following policies most highly: Allow K-12 teachers to carry concealed handguns (6.0), allow military personnel to carry on military bases (5.6), encourage the elimination of gun-free zones (5.3) and relax federal regulations that pressure companies to create gun-free zones (5.0). The top four policies for economists were the same, but in a different order: encourage the elimination of gun-free zones (7.9), relax federal regulations that pressure companies to create gun-free zones (7.8), allow K-12 teachers to carry concealed handguns (7.7), and allow military personnel to carry on military bases (7.7).

The general public seems to agree. An early July survey by the Trafalgar Group showed that a plurality of American general election voters believe that armed citizens are the most effective element in protecting you and your family in the case of a mass shooting. First on the list was “armed citizens” at 42%, followed by “local police” (25%) and “federal agents” (10%). [“None of the above” was the answer chosen by 23% of respondents.] A survey by YouGov in May – before the Uvalde, Texas, attack – found that by a margin of 51% to 37% American adults supported letting schoolteachers and administrations carry concealed handguns.