A few months ago, my work took me to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Chattanooga is a small city, population about 180,000, in the southeast of the state. Like the rest of the state, Chattanooga is by no means progressive. It didn’t have a "defund the police" movement or a progressive prosecutor. But even there (I learned, and some Manhattan Institute polling confirmed) there’s a widespread perception that crime is on the rise.

As I detail in a newly released MI report, though, the reality is more complicated. You can click through and read the whole thing, but the top line is that while Chattanooga—like many cities—had a violent crime problem, it’s mostly been brought under control. Facing a shrinking police staff, they focused their limited resources on bringing down violence using evidence-based strategies, and succeeded in doing so. But, I argue, they’ve done so at the expense of controlling disorder in the city—public homelessness, trash, drug-related violations, etc. This is what has prompted persistent unease even as crime has come down.

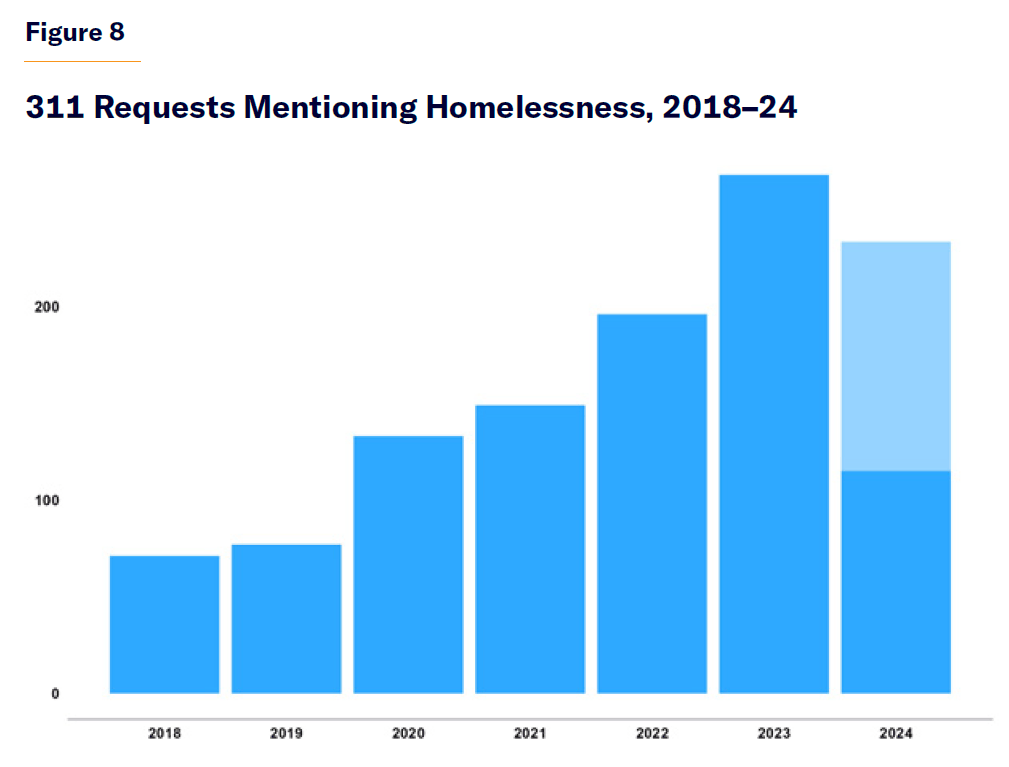

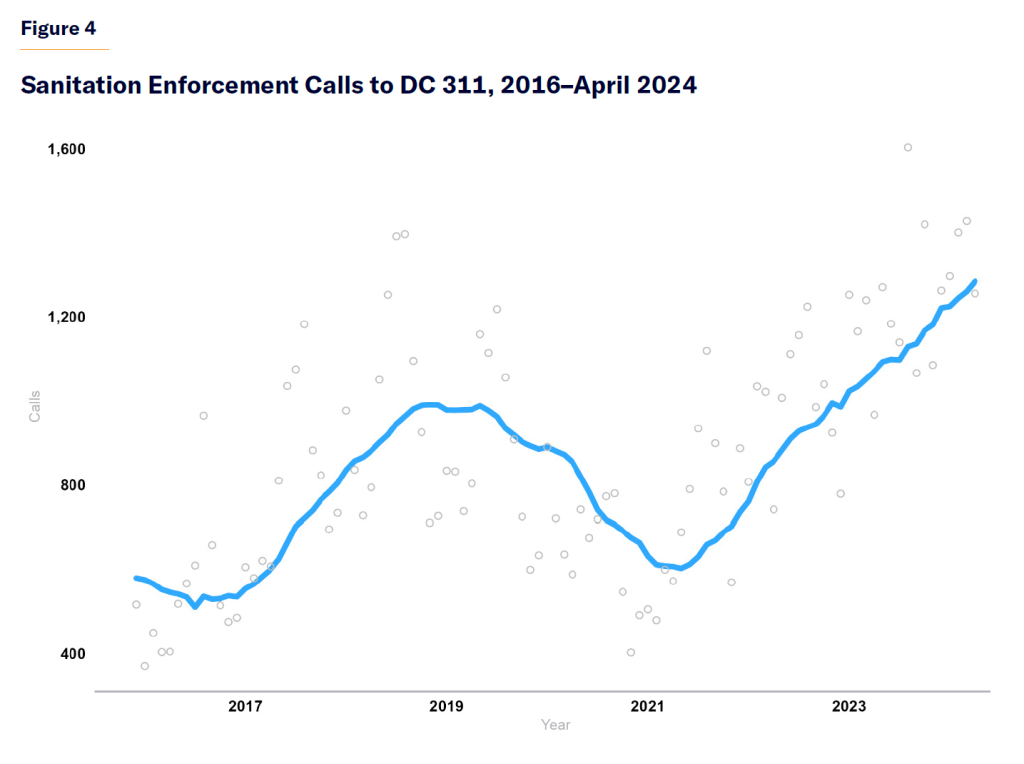

A similar pattern emerged in my recent report on crime in Washington, D.C. There, too, there are signs that disorder has risen, relative to both the pandemic and pre-pandemic, as the police have attended to it less. Unsheltered homelessness, unsanitary conditions, shoplifting, farebeating—all seem to have become more common in D.C. And those problems have come as a smaller police force has deprioritized order enforcement—if you look at table 2 of that report, you’ll see that arrests for minor crimes were down as much as 99% in 2023 relative to 2019.

I increasingly think this is a more general phenomenon. Disorder is not measured like crime—there is no system for aggregating measures of disorder across cities. But if you look for the signs, they are there. Retail theft, though hard to measure, has grown bad enough that major retailers now lock up their wares in many cities. The unsheltered homeless population has risen sharply. People seem to be controlling their dogs less. Road deaths have risen, even as vehicle miles driven declined, suggesting people are driving more irresponsibly. Public drug use in cities from San Francisco to Philadelphia has gotten bad enough to prompt crack-downs.

These are fuzzy signals, but they jibe with my personal experience (for whatever that is worth). In the half-dozen cities I’ve visited in the past year, visible disorder has been a common feature. Most conspicuous, in my experience, is the way that retailers have responded. It’s not just CVS; coffee shops seem to have gotten more hostile and less welcoming. This is, I suspect, because they are dealing with people who steal, cause a ruckus, or shoot up in the bathroom—disorderly behaviors that they have to deter before they cost them customers.

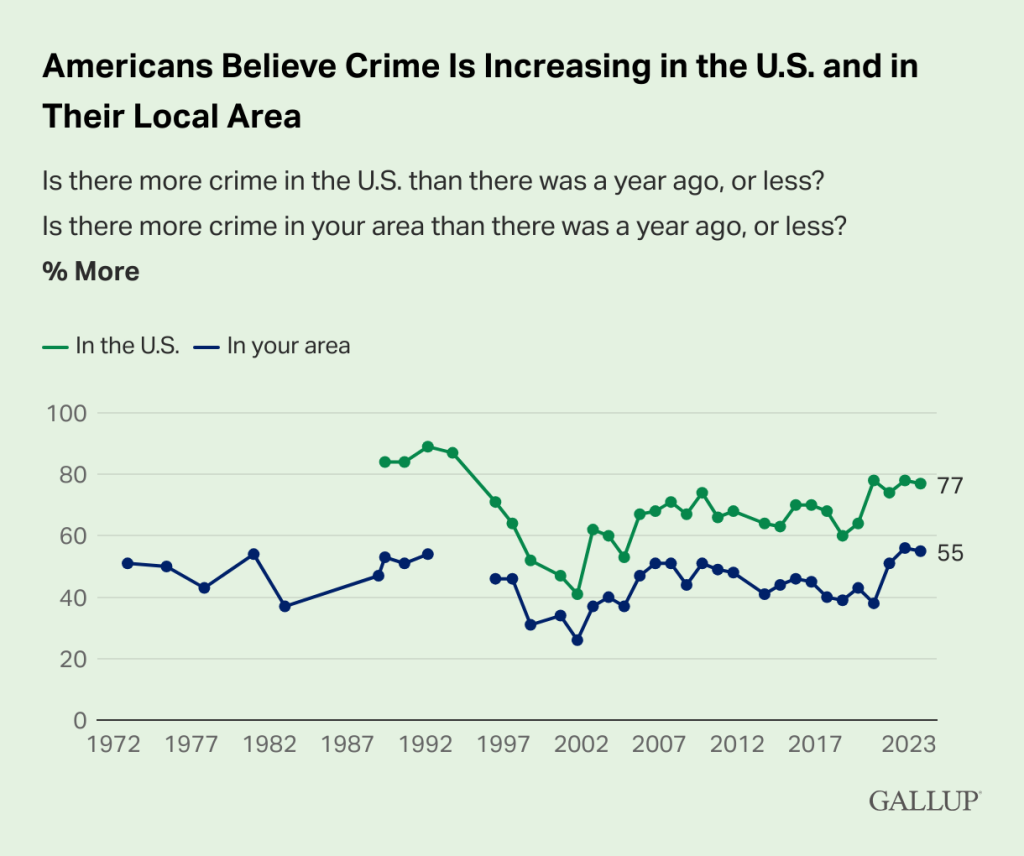

I was thinking about all of this in the context of the increasing mismatch between perception of crime and reality. Most kinds of crime are, by most measures, declining from their post-2020 peaks. That’s not true everywhere and across all crimes, but it appears to be true in the aggregate. But the result is some pundits engaging in what I labeled "crime-data trutherism"—insistence that the stats are fake, and that crime is actually surging. The public seems to agree, at least if Gallup is to be believed.

But what if something different is going on? We have evidence that perception of disorder drives perception of crime (after all, the former is much more common than the latter). What if violent, serious crime really is coming down, but disorder is rising—and causing people to continue to feel unsafe?

If that’s right, then the conversation needs to shift. Because while disorder is not murder, it is a real, substantial problem—one, I’ll argue, that should concern us far more than it currently does. Indeed, unless we start taking disorder seriously, we risk real and lasting social consequences.

What is Disorder, Anyway?

Part of the problem with talking about disorder is that it is hard to define. In Disorder and Crime, Northwestern political scientist researcher Wesley Skogan argues that disorder is in part distinguished from crime by the "untidiness" of its definition, and its dependence on often fuzzy normative values: "Unlike criminology, which avoids many complex conceptual issues simply by pointing to the statute books to classify behavior, the study of disorder necessarily examines conflicts over an uncodified set of norms." The concept joins together such distinct activities as building abandonment and public drinking. fIndeed, the challenge of defining disorder is part of what has made it a controversial topic, with critics contending that disorder is just another word that the powerful use for whatever it is the non-white, poor, and otherwise marginalized do.

Obviously, I think this last claim is not true. And I think most TCF readers can at least agree that descriptively, it is possible to identify certain phenomena as disorderly (even if normatively they may not be seen as bad). When we think of disorder, we might think of, for example:

- A man blasting loud music from his phone in a subway car;

- Teenagers spray-painting graffiti on a public park;

- A large homeless encampment taking over a city block;

- A man throwing his trash on the ground and walking away;

- A group of women selling sex on a street corner.

These are all disorderly behaviors (as distinguished from the physical disorder of an abandoned lot, e.g.). One feature that seems to join them is the way in which they affect public, as opposed to private, space. The guy playing loud music impinges on everyone else; the encampment and the litter both constrain use of the street corner. These behaviors, in other words, claim for the disorderly individual space which is nominally for everyone, and therefore which is meant to be shared by everyone.

From this little exercise, I want to take a first stab at a definition: Disorder is domination of public space for private purposes.

That’s a bit wordy, so let me break it down. "Public space" mean spaces which are meant to be enjoyed by everyone, usually by the largesse of either the state or some private charity. Living, working, or commuting in such spaces—as most city dwellers must—entails some degree of cooperation, so that everyone can get some part of the thing which no user has specific legal right to. Public space, that is, has to be shared. "Private purposes" are those things, which by contrast, we do only for ourselves, or which others might want to be excluded from our doing—listening to music, sleeping, producing trash, having sex, etc.

Of course, some private purposes are fine in public spaces, because they do not exclude others from use thereof. If I have a picnic in the park, it does not foreclose other people from enjoying their picnics, or from using my spot once I am gone. But if I play my music loudly, other people cannot listen to theirs; if I take over the street corner, or cover it in trash, other people cannot walk there. This is what I mean by "domination"—disorder is using a public space as though it is yours, in such a way as to make it hard for the rest of the public to use.

Disorder is the Natural State of the World

An odd feature of (many parts of) American society is how little litter there is. Yes, you can go to some cities and see a lot of it. But there is far less, even there, than there ought to be, relative to how much litter rational actors ought by default to produce.

What do I mean by this last claim? Littering—putting trash somewhere other than a designated receptacle—unburdens the litterer at, by default, essentially no cost. It is easy and, if done correctly, fun. (If you don’t believe me, try chucking cans off an overpass.) In most cases, littering has a positive expected value—the benefits (no longer having to carry trash) almost certainly outweigh the risk-adjusted cost of being caught and punished for littering. What I am saying, more precisely, is that littering is rational behavior. At the margins, rational people would litter much more than most people in America appear to.

Importantly, I am not saying that you ought to litter. Rather, I am saying there is an interesting mismatch between purely rational behavior and observed behavior. This mismatch, I might further argue, obtains with most behavior previously identified as disorderly. If I listen to my music without headphones, I get the music without the discomfort of headphones. If I sleep on the street, I get accommodations without the inconvenience of paying rent. If I spray paint graffiti on a public wall, I get all the joy of painting without having to clean up afterwards. Generally, private domination of public space happens because sharing space with others leaves less for me, and a rational person should want as much as he can get, net of the costs of getting it.

Disorderly behavior, in other words, is rational behavior. By taking more than my fair share, I am getting more than my fair share—and it is always better to have more than less. What this suggests is that left to their own devices, we should expect rational actors to engage in far more disorderly behavior at the margins than they actually do—that the world is, by nature, much more disorderly than it appears (at least in some places) to be.

Why, then, is there not more disorder? Why do people mostly not litter, or play their music on the train, or run prostitution rings out of their ADUs? If you ask people this, the extremely unsatisfying answer they usually give is "norms" or "culture," which are just ways of saying "we don’t do it because we don’t do it." A slightly more satisfying answer (to me, anyway) is that we don’t litter because of a variety of motivations, which are themselves the products of a diversity of institutions. Most people don’t litter because they are motivated by guilt, which is itself carefully cultivated by family members, peers, and social messaging. In some places, people don’t litter because they will be identified and incur a formal cost—if the HOA finds out that I have been throwing trash everywhere, for example, they may try to fine me. And sometimes (more often in the case of more serious disorder), people are not disorderly because they recognize the threat of formal criminal justice sanction—arrest, jailing, prosecution, incarceration, etc.

The concept I am using here is what criminologists and sociologists call "social control"—the regulation of individual behavior by social institutions through informal and formal means. Criminologists interested in social control often ask not "why is there crime," but "why isn’t there crime," with social control as the answer. Similarly, I am asking not "why is there disorder" but "why isn’t there disorder," which social control as the answer. Disorder is the default state of the world; order is an alternative state which can be brought about only by great and careful effort.

To the extent that America does currently have a disorder problem, I suspect that it is downstream of a cascading failure of social control. This manifests, of course, in the systematic depolicing that took place in the wake of the murder of George Floyd/the defund the police movement. But it’s also downstream of COVID, which reduced social control in a variety of ways. COVID shuttered shelters, jails, and schools. It also reduced the number of "eyes on the street," both in the short-run but also (thanks to the remote work exodus) over the long run. These two phenomena may be part of a broader failure of social control, as individual causes turn into a general reduction in the power of the institutions that govern our day-to-day lives, and stop disorder from creeping in.

Cities Cannot Work Without Order

What was the point, you may be wondering, of the preceding argument? The answer is that I think it is important to convince you that disorder matters, and to say why it matters, and why we should take it as more than a minor inconvenience.

After all, "disorder" is a freighted concept. To do some potted history: over the course of the latter half of the 20th century, disorder and decay became, alongside major crime, a serious problem in America’s major cities. In the 1990s, fed up citizens installed a wave of mayors (Giuliani, Daley, Riordan, Rendell, etc.) that focused on cleaning up the streets. A lot of this was backstopped by Broken Windows Theory, the idea (first articulated by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling) that disorder can create a doom loop that leads to major crime. But the aggressiveness and racial unevenness with which these strategies were prosecuted (e.g. in New York) bred an inevitable backlash against not just those particular strategies, but the whole idea of controlling disorder. Today, a certain strain of academic-cum-commentariat continues to maintain that even caring about things like how noisy your block is is backwards, racist, and just uncool, a sign that you cannot deal with living in the big city.

This last phenomenon is a textbook example of defining deviancy down. As police forces have shrunk and the criminal justice system decayed since the Great Recession, our capacity to do something about disorder has eroded. That erosion has of course been helped along by political efforts to hamstring disorder enforcement. But the erosion has also engendered the attempt to define away disorder as a problem per se—if we can’t make our cities less disorderly, pretend disorder is not a problem.

Yet, disorder is a problem. It is a problem instrumentally: the rise of remote work, among other trends, has made it easier than ever for Americans to leave the cities for the suburbs. I fear the end of the brief renaissance that, in the 2000s, reversed urban population decline. As I argue in my report on Chattanooga, many small American cities are currently competing over human capital that has fled out of high cost-of-living areas like San Francisco and New York. Those people will not want to live in your small city if it is disorderly, no matter how much you may wish it were otherwise.

But disorder is also a problem intrinsically. Cities (or towns, or communities of any kind) depend upon shared public space. This is true in a touchy-feely kind of way—it’s nice to have parks and sidewalks and so forth. But it’s also true in a cold, hard logical way. Cities’ comparative advantage is agglomeration and network effects: concentrating people in one place can create innovation that yields ore than linear returns. But that only is possible if people have shared public spaces in which to interact. Community life, of the sort that makes cities worth living in, is harder to live in the presence of disorder.

How to Combat Disorder

If disorder matters (epistemic status: pretty certain), and if American cities have a disorder problem (epistemic status: I think so, but want more systematic evidence), the policymakers should do something about it. But what? That would take a lot of words to answer, but I want to argue that the core to combating disorder is restoring public control of public space.

Public control of public space, recall, is not a natural phenomenon. It is something that is facilitated by formal and informal institutions. In the context of disorder, social control is about the sense of whether or not everyone has the right to use some public space or utility, or whether some private individual has excluded everyone else from its use unfairly.

Under normal conditions—when there’s not a big disorder problem—social control is maintained mostly by informal means. This is Jane Jacobs’s famous "eyes on the street"—if enough people are watching, most people will not feel they can engage in disorderly behavior. Why don’t people throw litter on the ground or urinate in public? Because they feel bad when other people notice them doing it.

But when the informal systems have lost their sway—as they perhaps have—then you need formal systems to step in. That doesn’t always mean the criminal justice system, to be clear. One reason for increasing public disorder, for example, is the explosion of chronic absenteeism since 2020. (Kids out of school cause trouble!) That’s a schools problem as much as, if not more than, a criminal-justice-system problem.

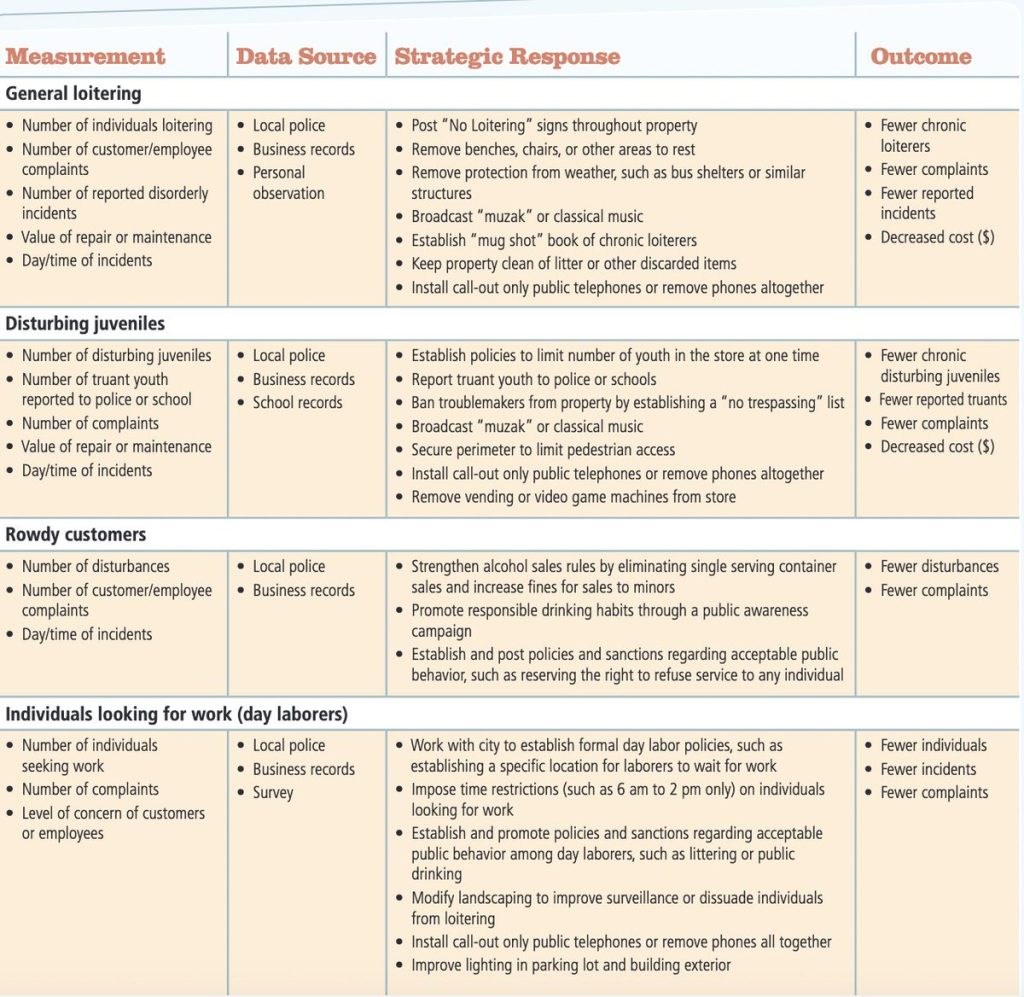

There are also lots of built environment interventions that can cheaply and easily reduce public disorder. Clearing vacant lots and greening public spaces are very hip interventions for reducing violent crime, but they probably also reduce disorder. Properties that generate disorder can be targeted for remediation by pressuring landlords into cleaning them up. Business owners can also try to harden spaces against disorder, e.g. by removing installations that attract disorderly behavior or broadcasting deterrent music.

That said, the criminal justice system, and particularly the police, are an integral part of disorder enforcement. The police are what I have called "the community’s credible threat"—the reason that social control works is that the individual engaged in deviant behavior knows that if he doesn’t comply with community standards, there will be a formal response. The grandma who tells rowdy kids to quiet down can do it in part because they won’t assault her, and they don’t assault her because they are afraid of the law.

Police can deter disorder simply by being a visible presence in communities. But they also can strategically target sources of disorder, helping to bring it to levels where the community can keep it under control. A recently updated meta-analysis of 56 studies of disorder policing found that such policing consistently reduces crime. But some approaches work better than others. The authors note that "aggressive order maintenance strategies"—arresting people indiscriminately—did not significantly reduce crime. But problem-oriented strategies, which tried to identify and redress specific sources of disorder, had often sizable effects without spill-overs.

This last insight is an important one for thinking about disorder (and crime more generally). A large share of disorder is generated by a small number of people and places—one drunk or one vacant lot, one uncontrolled bar or one guy shouting on the street, can ruin the whole experience for everyone else. Identifying these problem places and people, and remediating them—not exclusively through the criminal justice system—can bring disorder under control.

For a long time, disorder has been a taboo topic in our public discourse. If "crime is not the problem," then disorder certainly is considered not the problem. But I think the reality of public life in 2024 America is that disorder is the problem. And if we don’t act like that’s true, then people will flee the public spaces disorder prevents from flourishing. For that, we will be far poorer than if we just tried to address the issue head on.

This piece first appeared in Charles Lehman's Substack, The Casual Fallacy.