Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly portion of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson.

This week , another nail in the carbohydrate coffin as a small but rigorous study appearing in JCI Insight suggests that a low-carb, high-fat diet improves the metabolic syndromeeven when weight doesn’t change.[1]

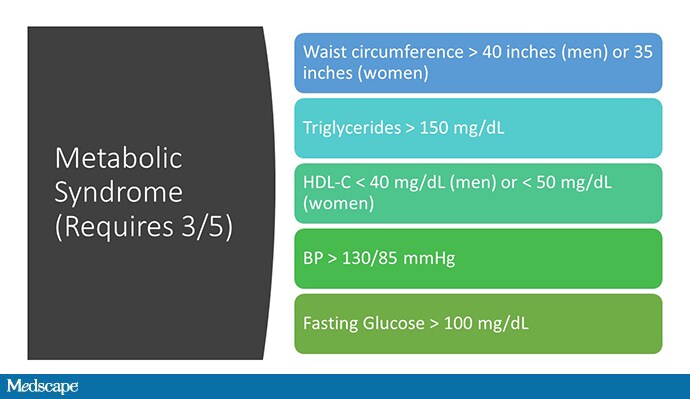

A quick reminder: Metabolic syndrome is defined as having at least three of the five factors on this list.

These factors seem to be tied to insulin resistance, so avoiding insulinsecretion (by limiting carb intake) has always made sense. Indeed, prior studies of low-carb diets have shown improvements in metabolic syndrome parameters, but those diets were also associated with weight loss, which led to a big question: Are low-carb diets beneficial because they help people lose weight or because there is something intrinsically bad about carbs themselves?

The JCI Insight paper finally gives us the answer, and the carb producers of the world aren’t going to like it.

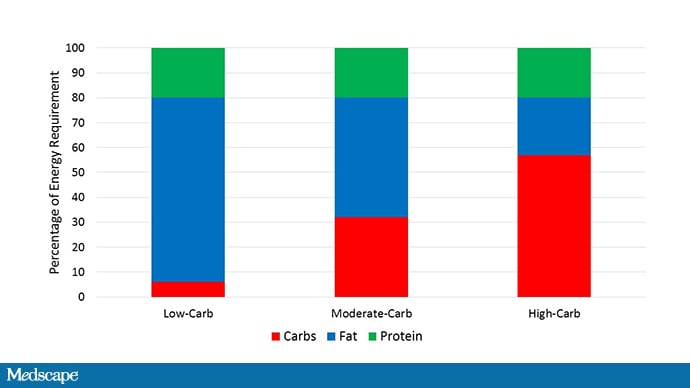

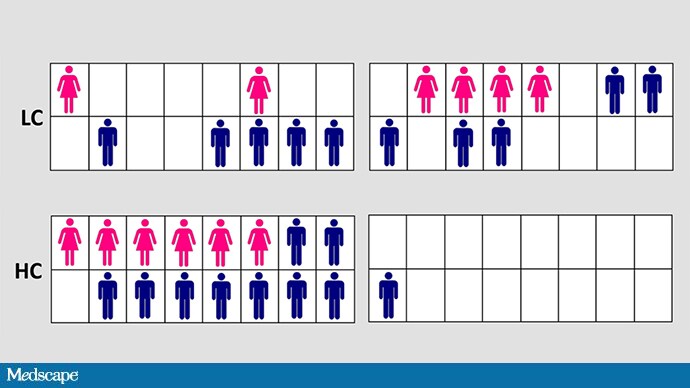

This was a physiologic study; 16 individuals were randomized to three different diets for 4-week periods.

Each individual randomly received either a low-carb diet, a moderate-carb diet, or a high-carb diet. Protein levels were fixed, so think of low-carb and high-fat as synonymous here. Each participant received each diet with 2-week washouts in between. They thus served as their own control—a smart design choice in a small study like this. Critically, the diets were designed to have a total caloric content that would not lead to weight changes. This was not a weight-loss intervention; it was a pure dietary change intervention.

After each 4-week diet, researchers measured a slew of biochemical parameters, and the tale of the tape was quite telling.

Looking at those metabolic syndrome parameters, there was no significant change in waist circumference or blood pressure, but fasting glucose levels and triglycerides were significantly lower in the low-carb diet group, while HDLwas higher.

In fact, of the 16 individuals in the trial, nine no longer met criteria for metabolic syndrome after 4 weeks of the low-carb diet. By comparison, only one individual no longer met the definition of metabolic syndrome after 4 weeks of the high-carb diet.

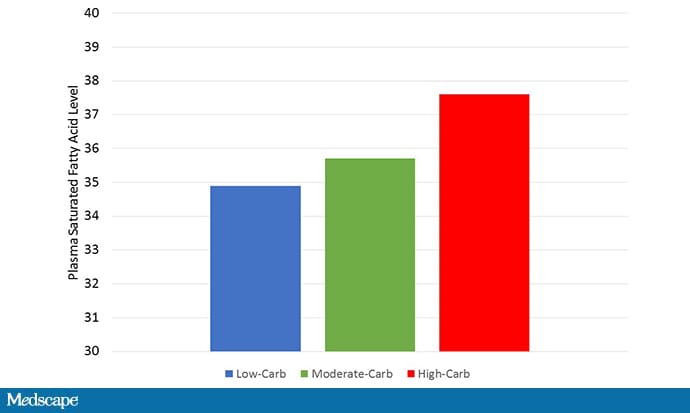

Other surprising findings: Blood levels of saturated fats were actually lower in the low-carb group, which had a substantially higher saturated fat intake (mostly in the form of cheese). This argues that the old canard “You are what you eat” doesn’t quite jibe with modern metabolic science.

Over the past five decades, carbohydrate consumption among Americans has skyrocketed, and rates of metabolic syndrome along with it. This study is the best so far to suggest that this relationship is not just driven by increases in weight but by the carbs themselves. The long-running war on fat may turn out to be a case of friendly fire.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.