The median age of new cases is dropping in some areas, but what does that mean? I see three possible explanations, and not all are good. Here is what we can look for in the numbers to figure out what is happening.

More Testing

As we do more testing in the community, we are able to capture more mild or even asymptomatic infections. In the early days of the epidemic, testing was reserved only for the sickest individuals. As older adults are more likely to have severe disease, the median age of cases skewed older. Since then, testing has become more accessible. Some workplaces even implement routine testing of employees. This means that we are detecting more infections in younger adults that we previously would have missed. As we uncover more mild infections with more testing, the median age can decline even with no change in the underlying epidemic.

If median age of new cases drops only because of more testing, we expect a few things:

- An increase in the number of cases detected across all age groups

- Test positivity to drop in all age groups

- With an increase in workplace testing, test positivity will drop the most in working-age adults, as many of those tested will be negative

- No change in hospitalizations because the underlying epidemic has not grown

Older People Are Better Protected

If the elderly are able to better protect themselves from infection, median age of new cases could drop with no change in testing. For example, COVID-19 has disproportionately affected nursing homes. Where efforts to protect nursing home residents are successful at preventing new outbreaks, the median age of cases could decline.

If the drop in median age of new cases is driven only by better protection of the elderly, we expect:

- A drop in the number of new cases in the elderly

- A drop in test positivity that is greatest among the elderly

- A drop in hospitalizations, observed after a lag

Young People Are Being Infected More

The first two scenarios are good outcomes, as more testing and better protection of the elderly are desirable. This last explanation is the not-good one. It means that young people are being infected even more than before. This could occur if there are many bar, nightclub, or workplace outbreaks. As economies reopen, many young people are going back to jobs where they cannot socially distance.

If median age drops only because young people are being infected more, we expect:

- Numbers of new cases in young people to rise

- Test positivity to increase in young people

- More young people being hospitalized, observed after a lag

Besides the fact that young people can face unknown long-term outcomes of infection, they can also inadvertently spread the virus to their communities. So the median age could start to creep back up if the virus spreads from young people out to their coworkers, family members, and neighbors. The more virus circulating in the community, the harder it will be for people to stay protected.

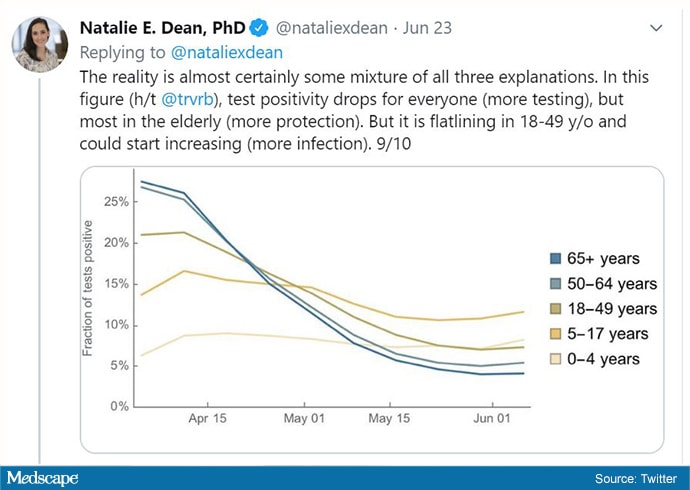

The reality is almost certainly some mixture of all three explanations and will vary from location to location. We can examine this graph using CDC’s COVIDView data on overall US trends in test positivity over time, broken out by age group. With the exception of children 0-4 years, test positivity drops for everyone (explanation 1: more testing). This drop is most substantial in the elderly (explanation 2: elderly are more cautious). But test positivity is flatlining in 18- to 49-year-olds and could start increasing as we see more outbreaks across the country (explanation 3: more infections in young people).

Test positivity in varying age groups from April 1, 2020, to June 1, 2020. (Source: Trevor Bedford, PhD, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington)

These data represent the United States, but we are better served by looking state by state or even at smaller geographic scales. Different areas may be experiencing different changes. We can use high-quality, age-stratified data on testing, cases, and hospitalizations to distinguish between these potential scenarios.

Natalie Dean, PhD, is an assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Florida in Gainesville. She specializes in emerging infectious diseases and vaccine study design.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.