Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

It’s just about the easiest, safest medical advice you can give: “Drink more water.” You have a headache? Drink more water. Tired? Drink more water. Cold coming on? Drink more water. Tom Brady famously attributed his QB longevity to water drinking, among some other less ordinary practices.

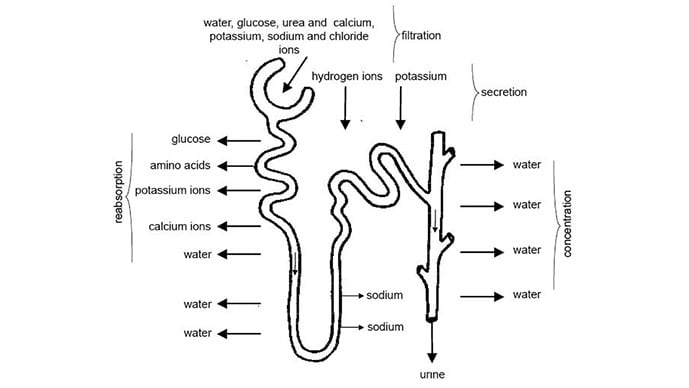

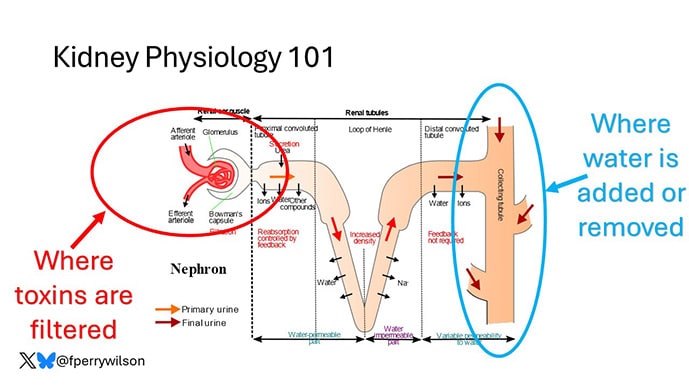

I’m a nephrologist — a kidney doctor. I think about water all the time. I can tell you how your brain senses how much water is in your body and exactly how it communicates that information to your kidneys to control how dilute your urine is. I can explain the miraculous ability of the kidney to concentrate urine across a range from 50 mOsm/L to 1200 mOsm/L and the physiology that makes it all work.

But I can’t really tell you how much water you’re supposed to drink. And believe me, I get asked all the time.

I’m sure of a couple of things when it comes to water: You need to drink some. Though some animals, such as kangaroo rats, can get virtually all the water they need from the food they eat, we are not such animals. Without water, we die. I’m also sure that you can die from drinking too much water. Drinking excessive amounts of water dilutes the sodium in your blood, which messes with the electrical system in your brain and heart. I actually had a patient who went on a “water cleanse” and gave herself a seizure.

But, to be fair, assuming your kidneys are working reasonably well and you’re otherwise healthy, you’d need to drink around 20 liters of water a day to get into mortal trouble. The dose is the poison, as they say.

So, somewhere between zero and 20 liters of water is the amount you should be drinking in a day. That much I’m sure of.

But the evidence on where in that range you should target is actually pretty skimpy. You wouldn’t think so if you look at the online wellness influencers, with their Stanleys and their strict water intake regimens. You’d think the evidence for the benefits of drinking extra water is overwhelming.

The venerated National Academy of Medicine suggests that men drink thirteen 8 oz cups a day (that’s about 3 liters) and women drink nine 8 oz cups a day (a bit more than 2 liters). From what I can tell, this recommendation — like the old “8 cups of water per day” recommendation — is pulled out of thin air.

I’m not arguing that we shouldn’t drink water. Of course, water is important. I’m just wondering what data there are to really prove that drinking more water is better.

Fortunately, a team from UCSF has finally done the legwork for us. They break down the actual evidence in this paper, appearing in JAMA Network Open.

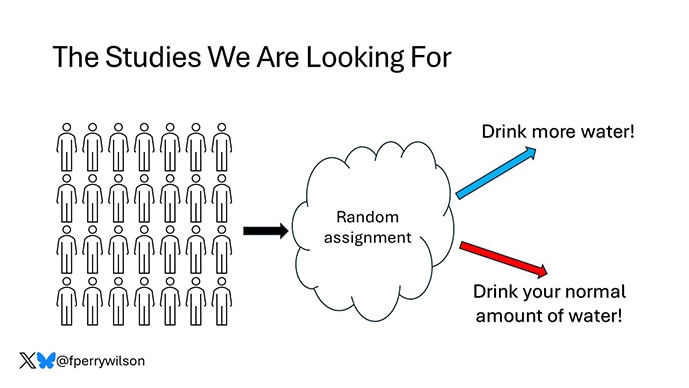

The team scoured the medical literature for randomized controlled trials of water intake. This is critical; we don’t want anecdotes about how clear someone’s skin became after they increased their water intake. We want icy cold, clear data. Randomized trials take a group of people and, at random, assign some to the intervention — in this case, drinking more water — and others to keep doing what they would normally do.

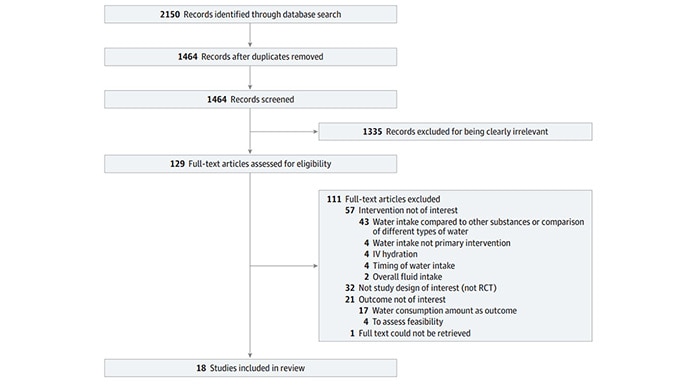

The team reviewed nearly 1500 papers but only 18 (!) met the rigorous criteria to be included in the analysis, as you can see from this flow chart.

This is the first important finding; not many high-quality studies have investigated how much water we should drink. Of course, water isn’t a prescription product, so funding is likely hard to come by. Can we do a trial of Dasani?

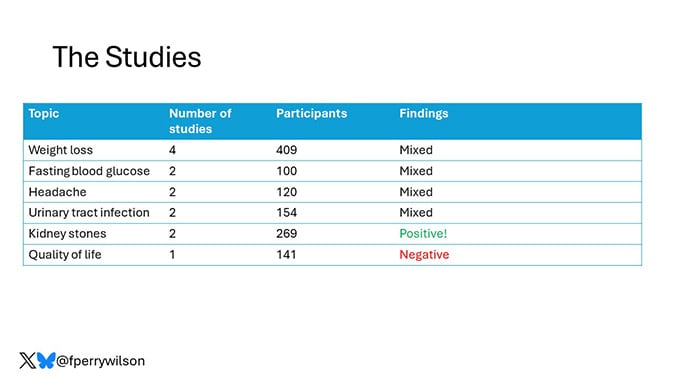

In any case, these 18 trials all looked at different outcomes of interest. Four studies looked at the impact of drinking more water on weight loss, two on fasting blood glucose, two on headache, two on urinary tract infection, two on kidney stones, and six studies on various other outcomes. None of the studies looked at energy, skin tone, or overall wellness, though one did measure a quality-of-life score.

And if I could sum up all these studies in a word, that word would be “meh.”

One of four weight loss studies showed that increasing water intake had no effect on weight loss. Two studies showed an effect, but drinking extra water was combined with a low-calorie diet, so that feels a bit like cheating to me. One study randomized participants to drink half a liter of water before meals, and that group did lose more weight than the control group — about a kilogram more over 12 weeks. That’s not exactly Ozempic.

For fasting blood glucose, although one trial suggested that higher premeal water intake lowered glucose levels, the other study (which looked just at increasing water overall) didn’t.

For headache — and, cards on the table here, I’m a big believer in water for headaches — one study showed nothing. The other showed that increasing water intake by 1.5 liters per day improved migraine-related quality of life but didn’t change the number of headache days per month.

For urinary tract infections, one positive trial and one negative one.

The best evidence comes from the kidney stone trials. Increasing water intake to achieve more than two liters of urine a day was associated with a significant reduction in kidney stone recurrence. I consider this a positive finding, more or less. You would be hard-pressed to find a kidney doctor who doesn’t think that people with a history of kidney stones should drink more water.

What about that quality-of-life study? They randomized participants to either drink 1.5 liters of extra water per day (intervention group) or not (control group). Six months later, the scores on the quality-of-life survey were no different between those two groups.

Thirsty yet?

So, what’s going on here? There are a few possibilities.

First, I need to point out that clinical trials are really hard. All the studies in this review were relatively small, with most enrolling fewer than 100 people. The effect of extra water would need to be pretty potent to detect it with those small samples.

I can’t help but point out that our bodies are actually exquisitely tuned to manage how much water we carry. As we lose water throughout the day from sweat and exhalation, our blood becomes a tiny bit more concentrated — the sodium level goes up. Our brains detect that and create a sensation we call thirst. Thirst is one of the most powerful drives we have. Animals, including humans, when thirsty, will choose water over food, over drugs, and over sex. It is incredibly hard to resist, and assuming that we have ready access to water, there is no need to resist it. We drink when we are thirsty. And that may be enough.

Of course, pushing beyond thirst is possible. We are sapient beings who can drink more than we want to. But what we can’t do, assuming our kidneys work, is hold onto that water. It passes right through us. In the case of preventing kidney stones, this is a good thing. Putting more water into your body leads to more water coming out — more dilute urine — which means it’s harder for stones to form.

But for all that other stuff? The wellness, the skin tone, and so on? It just doesn’t make much sense. If you drink an extra liter of water, you pee an extra liter of water. Net net? Zero.

Some folks will argue that the extra pee gets rid of extra toxins or something like that, but — sorry, kidney doctor Perry here again — that’s not how pee works. The clearance of toxins from the blood happens way upstream of where your urine is diluted or concentrated.

If you drink more, the same toxins come out, just with more water around them. In fact, one of the largest studies in this JAMA Network Open review assessed whether increasing water consumption in people with chronic kidney disease would improve kidney function. It didn’t.

I am left, then, with only a bit more confidence than when I began. I remain certain that you should drink more than zero liters and less than 20 liters every day (assuming you’re not losing a lot of water in some other way, like working in the heat). Beyond that, it seems reasonable to trust the millions of years of evolution that have made water homeostasis central to life itself. Give yourself access to water. Drink when you’re thirsty. Drink a bit more if you’d like. But no need to push it. Your kidneys won’t let you anyway.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He posts at @fperrywilsonand his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/how-much-water-should-we-drink-day-2024a1000lgp

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.