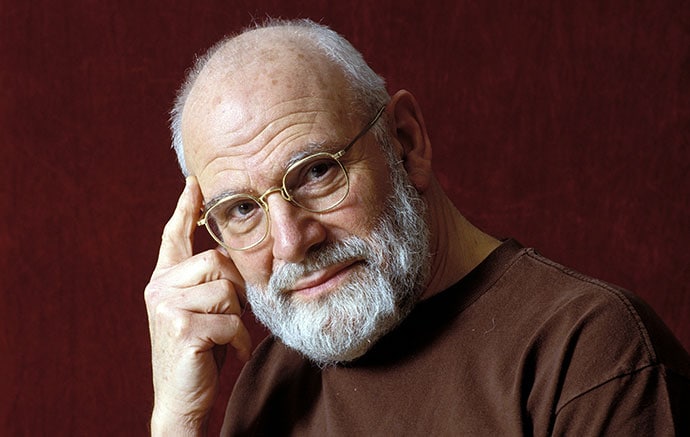

Oliver Sacks, neurologist and writer, died in 2015 at 82 years of age due to metastatic melanoma. The New York Times called him “one of the great clinical writers of the 20th century” and anointed him “poet laureate of contemporary medicine.”

Ten years later, a shocking article by New Yorker staff writer Rachel Aviv calls into question his many accolades. Her deep dive into Sacks’ letters and journals revealed that he sometimes embellished or invented his famous medical case studies.

In light of these revelations, how are we to reimagine his legacy?

Artistic License

There is a built-in tension in writing “creative nonfiction.” Writers may employ techniques such as allegory or metaphor while adhering to the facts, the “nonfiction.”

In practice, there may be some wiggle room with the facts: A case may be combined with another to anonymize the patient or clarify the symptoms. But when we read a medical case study, the reader trusts that the facts were not fabricated.

According to Masterclass, the first golden rule of creative nonfiction is to “Make sure everything is factually accurate…Obviously, if this complicates things or proves too hard for you, you can always consider writing a piece of fiction.”

A Prodigious Writer of Narrative Medicine

Sacks was a prolific writer. His erudite essays were published in respected magazines and journals, including The New Yorker, New York Times, and Nature. He normalized esoteric neurologic syndromes and made them palatable to the layperson.

Sacks’ publications dovetailed with the evolving practice of narrative medicine. In 2004, Dr Rita Charon, a literary scholar and professor at Columbia University, New York, wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine, “Narrative studies, many physicians are beginning to believe, can provide the ‘basic science’ of a story-based medicine that can honor the patients who endure illness and nourish the physicians who care for them.”

Most US medical schools, including my own, now include narrative medicine in their curricula.

Oliver Sacks’ detailed and compassionate case reports perfectly fit the paradigm of narrative medicine. Sacks became the archetype of the empathetic physician who listened to his patients and told their stories. Medical students identified him as the epitome of the physician/writer.

Neurology for Everyone

Sacks’ writing also achieved popular praise. His 1985 bestselling anthology of clinical cases The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, received international acclaim. His book Awakenings, which depicted the transformation of patients with encephalitis lethargica after L-dopa treatment, became a popular movie starring Robert DeNiro as a patient and Robin Williams as the inimitable Sacks.

My Hero

I had just completed my neurology residency when I read Sacks’ first book, Migraine. Like approximately 50% of neurologists, I also suffer from migraine. The book’s lyrical prose and graphic illustrations informed and reassured me about my own strange migraine auras. I immediately felt a kinship with this introspective and literary neurologist.

As a young physician, I would tell people that I liked to write and had published some creative nonfiction. They would often respond, “Oh, like Oliver Sacks!”

What a disturbing piece of news from The New Yorker that some, (it’s not clear how much), of Oliver Sacks’ medical reporting turns out to be fiction. In fact, doubts about the verity of his case histories date back more than 20 years, suspicions now confirmed by his own testimony.

In Sacks’ private papers, archived by the Oliver Sacks Foundation, he confesses to “lies,” “falsifications,” and “guilt.” He admits that stories in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat are:

“[T]hese odd narratives — half-report, half-imagined, half-science, half-fable, but with a fidelity of their own — are what I do, basically to keep MY demons of boredom and loneliness and despair away…I write out symbolic versions of myself.”

One of Sacks’ oldest friends, the director and writer Jonathan Miller, said of him, “Oliver has aspects of a Borgesian fantasist. He remembers things that have never happened…”

Why Gild the Lily?

In my early years as a physician, I published several works of narrative medicine about my patients. Their stories were so striking, so poignant, that they swirled inside my head until I wrote them down.

One young patient had daily drop attacks. It was one thing to listen to her mother describe these sudden falls, another to witness her crashing to the floor from my examining table during a routine office visit.

Another woman had lost her vision due to retinal degeneration. She knew she couldn’t see but cried when told that she was “blind.”

These stories did not require invention or embellishment. Their blunt truth made them troubling, unforgettable.

As my neurology career continued, I was keen to discover more strange cases like those reported by the renowned Dr Sacks, but I was chronically disappointed. I had cared for countless people with head injuries, but I never saw a patient with cerebral achromatopsia like the artist he described who could no longer see color after a concussion. I never saw autistic twins with a gift for prime numbers. I never saw a man mistake his wife for a hat. Was I not observant enough?

Yet I never suspected that Sacks’ patients might have been fabrications or their stories exaggerated. Why didn’t he stick with the facts? Weren’t the actual stories sufficiently compelling? As the de facto standard bearer for narrative medicine, why betray the genre?

Addicted to Patients

In a 1989 interview with Joanne Simon on The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, Sacks explained that he was not merely a clinical observer, “I’m addicted to patients. I can’t do without them. I need to have the feeling of these other lives, which become a part of my own. Empathy isn’t enough. I wish I could be in their shoes and know more exactly what it’s like.”

Apparently, Sacks conflated writing about his patients and writing about his favorite subject, himself. Sacks was a complex, introspective person (he participated in nearly 50 years of twice-weekly psychoanalysis). He wrote obsessively, including two memoirs and mountains of letters. A closeted homosexual for decades, he felt marginalized to the fringes of society, similar in some ways to his unusual patients.

Not Nonfiction

Rachel Aviv’s exposé forces us to reconsider the classification of Sacks’ work. His medical case studies cannot survive the scrutiny of fact-checking. Even one “half-fable” dismantles the premise that these stories constitute scientific observation. Sacks’ oeuvre can no longer be labeled “nonfiction.”

However, it’s not true that “Oliver Sacks made up everything,” as Jonathan Poletti would have his readers believe. For example, we know from Sacks’ home movies that the Awakenings patients really existed. We know that his chapter in An Anthropologist on Mars about Temple Grandin, famed autism advocate and animal behaviorist, was based on fact. (I interviewed Temple Grandin, and she confirmed this.)

Conclusion

We can honestly and enthusiastically acknowledge Oliver Sacks as a beloved neurologist and marvelous writer. But perhaps librarians and booksellers should transfer his books to the fiction shelves, where they may be appreciated without caveat.

Sacks would likely agree with Camus that, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.”

Andrew Wilner, MD, is a professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and a seasoned neurologist and epilepsy expert who has mastered the less conventional locum career path. He is the author of four books, including Bullets and Brains, and hosts the podcast “The Art of Medicine with Dr. Andrew Wilner.”

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/oliver-sacks-writer-fact-or-fiction-2026a100011f

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.