Research funders from France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlandsand eight other European nations have unveiled a radical open-access initiative that could change the face of science publishing in two years — and which has instantly provoked protest from publishers.

The 11 agencies, who together spend €7.6 billion (US$8.8 billion) in research grants annually, say they will mandate that, from 2020, the scientists they fund must make resulting papers free to read immediately on publication (see ‘Plan S players’). The papers would have a liberal publishing licence that would allow anyone else to download, translate or otherwise reuse the work. “No science should be locked behind paywalls!” says a preamble document that accompanies the pledge, called Plan S, released on 4 September.

“It is a very powerful declaration. It will be contentious and stir up strong feelings,” says Stephen Curry, a structural biologist and open-access advocate at Imperial College London. The policy, he says, appears to mark a “significant shift” in the open-access publishing movement, which has seen slow progress in its bid to make scientific literature freely available online.

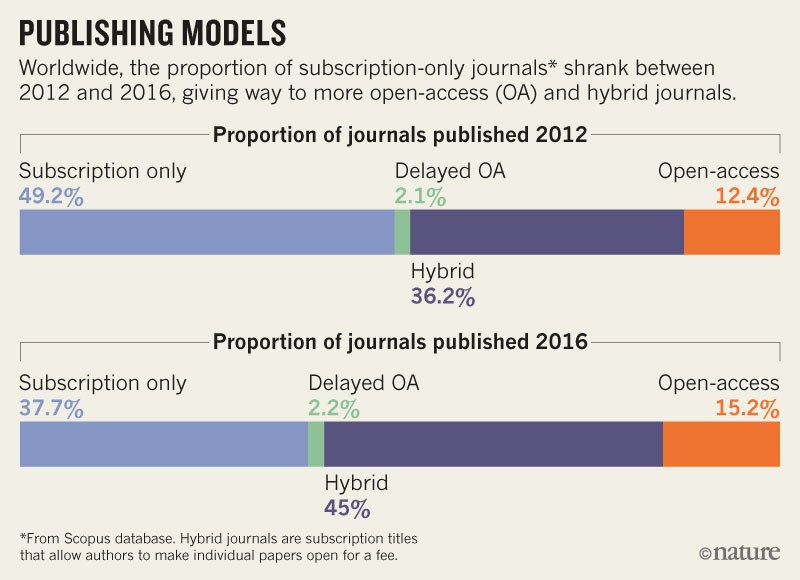

As written, Plan S would bar researchers from publishing in 85% of journals, including influential titles such as Nature and Science. According to a December 2017 analysis, only around 15% of journals publish work immediately as open access (see ‘Publishing models’) — financed by charging per-article fees to authors or their funders, negotiating general open-publishing contracts with funders, or through other means. More than one-third of journals still publish papers behind a paywall, and typically permit online release of free-to-read versions only after a delay of at least six months — in compliance with the policies of influential funders such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

And just less than half have adopted a ‘hybrid’ model of publishing, whereby they make papers immediately free to read for a fee if a scientist wishes, but keep most studies behind paywalls. Under Plan S, however, scientists wouldn’t be allowed to publish in these hybrid journals, except during a “transition period that should be as short as possible”, the preamble says.

Source: Universities UK

“Hybrid journals were always viewed as a step towards full open access. They haven’t succeeded as a transitionary measure,” says David Sweeney, who chairs Research England, one of the funding agencies subsumed under UKRI, the United Kingdom’s national research funder. The plan also states that funders will cap the amount they are willing to pay for open-access publishing fees, but doesn’t lay out what charge would be too much.

Putting the ‘s’ in Plan S

The initiative is spearheaded by Robert-Jan Smits, the European Commission’s special envoy on open access. (The ‘S’ in Plan S can stand for ‘science, speed, solution, shock’, he says). In addition to the French, British and Dutch funders, national agencies in Austria, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland and Slovenia have also signed, as have research councils in Italy and Sweden.

“Paywalls are not only hindering the scientific enterprise itself but also they are an obstacle [to] the uptake of research results by the wider public,” says Marc Schiltz, president of Science Europe, a Brussels-based advocacy group that represents European research agencies and which officially launched the policy.

Smits says he took inspiration from the open-access policy of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the global health charity based in Seattle, Washington, which also demands immediate open-access publishing. Because Plan S forbids hybrid publishing — and because it involves multiple funders — its impacts could be even more far-reaching than the Gates policy, which by itself has nudged several influential journals to change their publishing models.

Not quite all aboard

Despite Smits’ role, the European Commission hasn’t itself signed the plan. But Smits says that he expects the requirements to be integrated into the terms and conditions of future research grants from the commission. That hasn’t happened yet because policymakers are still debating the details of its next research and innovation programme, Horizon Europe, which begins in 2021 and will be worth €100 billion over 7 years. Smits says he expects more funding agencies to join, and that he will discuss the plan in the United States next month with White House officials, scientific academies and universities.

“The plan is roughly what one would want after about 15 years of funder experimentation with weaker policies,” says Peter Suber, director of the Harvard Open Access Project and the Harvard Office for Scholarly Communication in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We are very supportive of the ambition set out in Plan S,” adds Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a large private biomedical charity in London. He says the funder is finalizing a new open-access policy.

But national research agencies in some of Europe’s leading scientific nations, such as Switzerland, Sweden and Germany, have not yet signed. In Sweden’s case, this is because it has doubts over the tight timetable, says Sven Stafström, head of the country’s research council. He says the council agrees with the aims of Plan S and will review its position on the document at a board meeting later this month. Peter Strohschneider, president of Germany’s national research council, the DFG, says his council hadn’t signed because of the way the plan mandates recipients of public funding to specific forms of open access. “We request our researchers to publish their findings from DFG grants open access but we do not mandate them,” he said. He also cautioned that if researchers were all told to publish in open-access journals, costs of publishing could increase.

Sweeney says that, in the United Kingdom, it isn’t possible to calculate how much funders will need to pay under open-access publishing without a fuller picture of how publishers will respond. “What it costs depends on the reaction of the industry. This is a statement about principles, it is not a statement about [publishing] models,” he says.

And for Stan Gielen, president of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), Plan S goes beyond the economics of publishing. “This is part of a bigger transition towards open science and a re-evaluation of how we measure science and the quality of scientists,” he says.

Publisher concerns

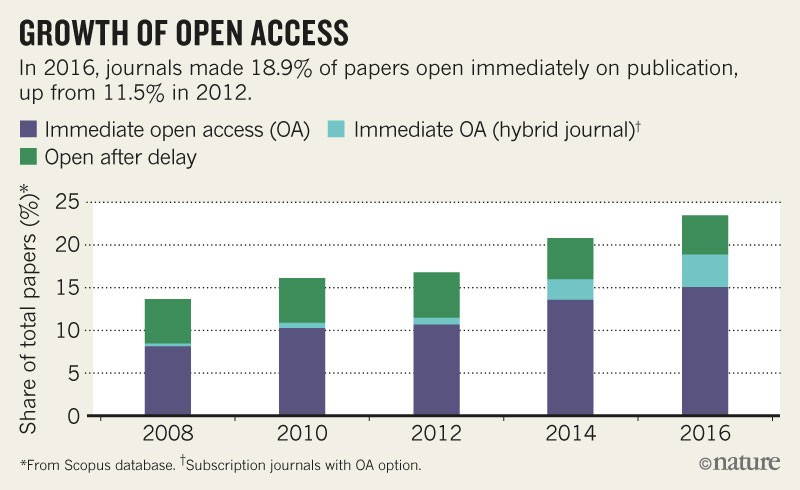

Asked for comments ahead of the plan’s launch, publishers said they had serious concerns — particularly around the banning of hybrid journals. A spokesperson for the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers (STM), based in Oxford, UK, which represents 145 publishers, told Nature’s news team that although it welcomed funders’ efforts to expand access to peer-reviewed scientific works, some sections of Plan S “require further careful consideration to avoid any unintended limitations on academic freedoms”. In particular, the STM spokesperson said, banning hybrid journals — which have delivered a lot of growth in open-access articles (see ‘Growth in open access’) — could “severely slow down the transition”. The publishing giant Elsevier said it supported the STM’s comments.

Source: UUK (2017)/BMC Med. 10, 124 (2012).

In another statement, a spokesperson for Springer Nature said: “Research, and the communication of it, is global. We urge research funding agencies to align rather than act in small groups in ways that are incompatible with each other, and for policymakers to also take this global view into account.” Removing publishing options from researchers “fails to take this into account and potentially undermines the whole research publishing system”, the statement added. (Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its publisher).

Meanwhile, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a non-profit organization that publishes the journal Science, said that the model outlined in Plan S “will not support high-quality peer-review, research publication and dissemination”. Implementing the plan would “be a disservice to researchers” and “would also be unsustainable for the Science family of journals”, the AAAS says.

Smits, however, says that it is essential that high-quality peer review remains part of the science publishing system under Plan S. “Publishers are not the enemy. I want them to be part of the change,” he says.

S for sanction?

Only a few funding agencies currently punish researchers who decide not to follow their open-access policies — including the Wellcome Trust and the NIH. But under Plan S, funders promise to “sanction non-compliance”, the initiative states. Smits suggests that a possible sanction for researchers who don’t comply could be withholding the final instalment of a grant, which is usually paid once a project is completed. But this, and other details such as the amount that funders are willing to pay to publish each article, will be worked out by the coalition in the run-up to 2020, he says.

Many European funders have been trying to make research free to read by brokering new ‘read-and-publish’ contracts with publishers, in which a single fee is paid to cover both the costs of reading paywalled research and of authors publishing under open-access terms. But some of the funders who have signed Plan S — including those in the Netherlands and Norway — now say they don’t intend to pay any more subscription fees beyond a transitionary period.

If other funders follow the Plan S idea, it could spell the end of scientific publishing’s dominant subscription business model, says John-Arne Røttingen, the head of Norway’s research council. “Subscription journals will see the opportunity to flip their business models into a system where what is paid for is the solid peer review, editorial reviewing and electronic dissemination of research results,” he says.

But Curry cautions that shifting from a subscription to an open-access business model around the world, as Plan S signers advocate, could bring a new challenge — how scientists in poorer nations will be able to afford to publish open-access work. “That has to be part of the conversation,” he says.