Revenue of $42.7M (+5749.3% Y/Y) misses by $11.67M.

Search This Blog

Monday, August 5, 2019

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals EPS beats by $0.09, misses on revenue

Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ:ARWR): Q3 GAAP EPS of $0.21 beats by $0.09.

Whole body vibration shakes up microbiome, cuts inflammation in diabetes

In the face of diabetes, a common condition in which glucose and levels of destructive inflammation soar, whole body vibration appears to improve how well our body uses glucose as an energy source and adjust our microbiome and immune cells to deter inflammation, investigators report.

For the first time they have described how regular use of whole body vibration can create this healthier mix by yielding a greater percentage of macrophages — cells that can both promote or prevent inflammation — that suppress rather than promote.

In their mouse model, investigators at the Medical College of Georgia and Dental College of Georgia at Augusta University have also shown that whole body vibration alters the microbiome, a collection of microorganisms in and on our body, which help protect us from invaders and, in the gut, help us digest food.

Changes they saw included increasing levels of a bacterium that makes short chain fatty acids, which can help the body better utilize glucose, they report in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Glucose is used by the body for fuel but at high levels promotes inflammation, insulin insensitivity and ultimately can cause diabetes.

While there were other changes, the most dramatic they documented was the 17-fold increase in this bacterium called Alistipes, a gut bacterium not typically in high supply there but known to be proficient at making short chain fatty acids which, in turn, are “very good” at decreasing inflammation in the gut, says Dr. Jack Yu, chief of pediatric plastic surgery at MCG. Alistipes, which helps ferment our food without producing alcohol, generally improves the metabolic status of our gut and makes us more proficient at using the glucose we consume for energy.

When they saw this, co-corresponding authors Yu and Dr. Babak Baban, immunologist and interim associate dean for research at DCG, immediately thought that giving a dose of the bacterium, like you would a medication, with a smaller dose of whole body vibration — in this case 10 minutes versus 20 minutes five times weekly — might work just as well, and it did, they report.

It what appears to be this good chain reaction, when Alistipes went up, glucose use and the macrophage mix also improved, Baban says. “The sequencing is not yet completely clear,” Yu says, “But it appears to be a closed loop, feed forward, self-magnifying cycle.”

Our microbiome, like a casserole, is in layers and one way whole body vibration may work is by rearranging those layers, Baban says, but they reiterate that no one is certain just how whole body vibration works in this or other scenarios, like as an exercise mimic without all the proactive movement.

But it appears to help address a key concern in diabetes and many common diseases: inflammation. While acute inflammation helps us fight disease, chronic inflammation helps start and sustain a variety of diseases from cardiovascular problems to cancer as well as diabetes.

With rates of inflammation-producing obesity and related type 2 diabetes increasing — even in children — new therapies that can directly help avoid the health consequences are needed, they write. They add that while more work is needed, whole body vibration might be one widely applicable and generally safe approach to use.

Macrophages, which promote inflammation, called M1, and suppress inflammation, called M2, play an important role in regulation of the inflammatory response. The inflammatory status of macrophages also influences the gut microbiome and vice versa.

In Baban and Yu’s mouse model of type 2 diabetes, where circulating glucose levels are high, they wanted to know how whole-body vibration affected the inflammatory status of macrophages and the diversity of the microbiome. They theorized their diabetes model would have more M1s, and that whole body vibration would result in more M2s and yield changes in the microbiome as well.

They found both a significant increase in the number of M2s as well as increases in levels of other anti-inflammatory molecules like the cytokine IL-10, in both normal mice and their diabetes mouse model after vibration. In fact, whole body vibration restored M2 levels to that of normal controls.

In the microbiome, they saw numerous shifts but by far the most significant was the increase in Alistipes and a general decrease in the diversity of the microbiome.

They note that while more diversity is generally considered a good thing, in this case the shift likely resulted from an increase in species like Alistipes, which can produce short chain fatty acids like butyrate, which result from the fermentation of dietary fiber in our gut and which feed inhabitants of the microbiome, are highly anti-inflammatory and can help reverse ill effects of high-fat diets, they write.

Theirs is the first study to document crosstalk between the microbiome and innate immunity by altering the macrophage mix with whole body vibration. Innate immunity is a sort of basic defense that immediately responds to invaders in the body and includes physical barriers like the skin as well as immune cells like macrophages, which are key to this response. In this scenario, macrophages, for example, release other cells called cytokines that help trigger inflammation. Adaptive immunity is when the body makes a specific cell, like an antibody, to target a specific invader.

They note that it’s still impossible to know whether the microbiome or macrophage shift comes first but theorize that making more glucose available to macrophages fosters inflammation and insulin resistance.

Another experiment they want to do to better define the order, is to delete the macrophages and see if they still see the other effects, Baban says.

But either way, the investigators say the clear interaction provides more evidence that whole body vibration can turn down inflammation.

The microbiome lives in the mouth, gut, vagina and skin — mostly in the gut– at points where our body comes in contact with foreign items to help protect us from invaders. In the gut it helps us digest and use our food.

Scientists have found more than 8 million genes represented in the bacteria, fungi and viruses that comprise a healthy human microbiome while the human himself has more like 20,000 to 25,000 genes. Obesity has been associated with a less-diverse microbiome, which is actually more efficient at digesting food.

In diabetes, whole body vibration is known to reduce ill effects like excessive urine production and excessive thirst, Yu reported in 2012 to the Third World Congress of Plastic Surgeons of Chinese Descent. That work was in a mouse model, which mimicked overeating adolescents. Vibration also reduced inflammation levels, including shifts in some immune cell levels. Vibration also was better than drugs at reducing A1C levels, which provide a better idea of your average blood sugar levels than a fasting glucose by showing what percentage of your oxygen-carrying hemoglobin is routinely coated with sugar. High glucose, or blood sugar levels, may result in sugar binding to cells and other places inside the body where it can alter function.

“Hyperglycemia is not good,” says Yu. “When it happens you perturb the normal.”

While Alistipes, which does not survive well outside the body, is not currently a part of probiotics or even yogurt cultures, for these studies the investigators used levels of other bacterium, like lactobacillus, found in yogurt to determine how much to give when they tried the Alistipes as a medicine adjunct to whole body vibration.

Alistipes is found in plants, and levels have been shown to be decreased in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn’s. Higher levels have been associated with depression, and high levels can be found in the gut of hibernating bears.

A 2017 study published in Endocrinology by Drs. Alexis Stranahan and Meghan E. McGee-Lawrence at MCG, see eurekalert.org/multimedia/pub/135777.php, provided evidence that in their animal model of obesity and diabetes, whole body vibration was essentially the same as walking on a treadmill at reducing body fat and improving muscle and bone tone, including reducing seriously unhealthy fat around the liver, where it produces damage similar to excessive drinking.

###

The Milford B. Hatcher Endowment helped support Baban and Yu’s research.

To see the full study visit https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/20/13/3125/htm.

Manipulating brain cells using smartphone

A team of scientists in Korea and the United States have invented a device that can control neural circuits using a tiny brain implant controlled by a smartphone.

Researchers, publishing in Nature Biomedical Engineering, believe the device can speed up efforts to uncover brain diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, addiction, depression, and pain.

The device, using Lego-like replaceable drug cartridges and powerful bluetooth low-energy, can target specific neurons of interest using drug and light for prolonged periods.

“The wireless neural device enables chronic chemical and optical neuromodulation that has never been achieved before,” said lead author Raza Qazi, a researcher with the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and University of Colorado Boulder.

Qazi said this technology significantly overshadows conventional methods used by neuroscientists, which usually involve rigid metal tubes and optical fibers to deliver drugs and light. Apart from limiting the subject’s movement due to the physical connections with bulky equipment, their relatively rigid structure causes lesion in soft brain tissue over time, therefore making them not suitable for long-term implantation. Though some efforts have been put to partly mitigate adverse tissue response by incorporating soft probes and wireless platforms, the previous solutions were limited by their inability to deliver drugs for long periods of time as well as their bulky and complex control setups.

To achieve chronic wireless drug delivery, scientists had to solve the critical challenge of exhaustion and evaporation of drugs. Researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology and the University of Washington in Seattle collaborated to invent a neural device with a replaceable drug cartridge, which could allow neuroscientists to study the same brain circuits for several months without worrying about running out of drugs.

These ‘plug-n-play’ drug cartridges were assembled into a brain implant for mice with a soft and ultrathin probe (thickness of a human hair), which consisted of microfluidic channels and tiny LEDs (smaller than a grain of salt), for unlimited drug doses and light delivery.

Controlled with an elegant and simple user interface on a smartphone, neuroscientists can easily trigger any specific combination or precise sequencing of light and drug deliveries in any implanted target animal without need to be physically inside the laboratory. Using these wireless neural devices, researchers could also easily setup fully automated animal studies where behaviour of one animal could positively or negatively affect behaviour in other animals by conditional triggering of light and/or drug delivery.

“This revolutionary device is the fruit of advanced electronics design and powerful micro and nanoscale engineering,” said Jae-Woong Jeong, a professor of electrical engineering at KAIST. “We are interested in further developing this technology to make a brain implant for clinical applications.”

Michael Bruchas, a professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine and pharmacology at the University of Washington School of Medicine, said this technology will help researchers in many ways.

“It allows us to better dissect the neural circuit basis of behaviour, and how specific neuromodulators in the brain tune behaviour in various ways,” he said. “We are also eager to use the device for complex pharmacological studies, which could help us develop new therapeutics for pain, addiction, and emotional disorders.”

The researchers at the Jeong group at KAIST develop soft electronics for wearable and implantable devices, and the neuroscientists at the Bruchas lab at the University of Washington study brain circuits that control stress, depression, addiction, pain and other neuropsychiatric disorders. This global collaborative effort among engineers and neuroscientists over a period of three consecutive years and tens of design iterations led to the successful validation of this powerful brain implant in freely moving mice, which researchers believe can truly speed up the uncovering of brain and its diseases.

###

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea, U.S. National Institute of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Mallinckrodt Professorship.

Humana picks up Louisiana Medicaid contract

Humana’s (HUM -3.1%) Health Benefit Plan of Louisiana is one of four managed care providers selected by the Louisiana Department of Health to provide services and benefits to the state’s Medicaid-eligible adults and children beginning in January 2020.

The other three providers are AmeriHealth Caritas Louisiana, Community Care Health Plan of Louisiana and United Healthcare Community Plan (UNH-2.4%).

CMS prescribes payment fix to resuscitate US antibiotic industry

As the UK experiments with a subscription-style payment system to resuscitate the fledgling antibiotic industry — in the United States, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is working on restructuring the payment apparatus for new antibiotics to revitalize antimicrobial development and rescue existing manufacturers.

For one of the biggest threats to global health, the lion’s share of antibiotic development is taking place in a handful of labs of small biopharma companies as a majority of their larger counterparts focus on more lucrative endeavors. In recent months, a handful of antibiotic developers — including Achaogen and Tetraphase — have seen their value go up in smoke as feeble sales frustrate growth.

It is no secret that the industry players contributing to the arsenal of antimicrobials are fast dwindling. Drugmakers are enticed by greener pastures, compared to the long, arduous and expensive path to antibiotic approval that offers little financial gain as treatments must be priced cheaply, and often lose potency over time as microbes grow resistant to them. Consequently, there have been no new class of antibiotics approved since the 1980s — and today, roughly 700,000 deaths annually are attributed to drug-resistant bacteria, according to the WHO.

Medicare beneficiaries account for the majority of both new antimicrobial resistance (AMR) cases and fatalities in the United States, CMS administrator Seema Verma noted in the journal Health Affairs on Friday.

Medicare beneficiaries account for the majority of both new antimicrobial resistance (AMR) cases and fatalities in the United States, CMS administrator Seema Verma noted in the journal Health Affairs on Friday.

In the United States, incentives are already in place to push drugmakers to develop antibiotics, such as funding support through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and regulatory reforms such as the Limited Population Pathway for Antibacterial and Antifungal Drugs (LPAD) — but the industry is clamoring for the passage of “pull incentives,” or policy measures to increase the value of a marketed antibiotic by rewarding drugmakers only after their antibiotic is approved.

Existing incentives, “while well-intentioned…appear to have been insufficient, as they focused exclusively on bolstering the development pipeline without removing the blockage created by issues with payment,” Verma conceded.

To remedy the existing set of “misaligned incentives,” the CMS has finalized new rules to reform antibiotic payments from 2020.

Under the current system, hospitals bundle together the costs of all the services for a given diagnosis into what is called a diagnosis-related group (DRG). Congress implemented the DRG system in 1983 to control hospital reimbursements by replacing retrospective payments with prospective payments for hospital charges. The CMS assigns each DRG a weight, which in conjunction with hospital-specific data, is used to determine reimbursement.

This system tends to incentivize hospitals to prescribe cheaper, generic antibiotics that are not engineered to tackle drug-resistant infections. “This, coupled with the comparatively lower revenue ceiling for antibiotics due to their low prescription volumes, has caused new antibiotics to become endangered innovations,” she wrote.

CMS is, therefore, changing the severity level designation from non-CC to CC for codes specifying AMR — the “CC” designation indicates the presence of a complication or comorbidity in a given inpatient case that requires the hospital to dedicate more resources for the care of that patient than typically required for the specific diagnosis. Classifying drug resistance in this way will compel higher payments to hospitals treating patients with AMR, crafting a pathway for doctors to prescribe appropriate new antibiotics without disrupting hospital budgets. CMS will also continue to “explore whether additional reforms are needed to recalibrate DRGs to better account for the clinical complexity of drug resistance,” Verma said.

Another measure being taken by the CMS is to amend the New Technology Add-On Payments (NTAPs) system as it relates to AMR, which is “uniquely diminished for antibiotics.” NTAP was created in 2000 as a “time-limited enhanced payment for new drugs or devices” to smooth the entry for fresh products while providing time for the relevant DRG to recalibrate to accommodate payment for new products. “However, stakeholder feedback nearly two decades later suggests that implementation of the NTAP through rulemaking by CMS — both in terms of eligibility criteria and payment — is insufficient to support innovation for antibiotics,” Verma acknowledged.

This is partly due to the fact that antibiotic developers struggle to meet the agency’s “substantial clinical improvement” criteria as they are traditionally given the green light by the FDA on the basis of trials that show their products are non-inferior to existing antibiotics. “(H)alf of previous antibiotic applications for NTAPs have been rejected because of a failure to satisfy this specific criterion,” Verma said.

Another issue is that the payment level for the NTAP is set at 50% of either the cost of the new product or the difference between the DRG payment and the total covered cost of the particular case. However, this threshold is insufficient to incentivize hospitals to file for an NTAP payment due to the low antibiotic prescription volumes for resistant infections.

To remedy these structural challenges, the CMS — the United States’ largest payer — has finalized an alternative NTAP pathway that does not include the SCI criteria and increases the NTAP from 75% from 50% for new antibiotics that have been granted as Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) status.

Last year, former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb suggested a “licensing model” in which acute care institutions that prescribe antimicrobial medicines would pay a fixed licensing fee for access to these drugs, granting them the right to use a certain number of annual doses.

Alzheimer’s Tied to Altered Liver Function

Study Authors: Kwangsik Nho, Alexandra Kueider-Paisley, et al.

Target Audience and Goal Statement:

Gastroenterologists, neurologists, geriatricians, hepatologists, internists, primary care physicians, family physicians

The goal was to examine potential associations between liver dysfunction and the development of Alzheimer’s disease, measures of cognition, and results using neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers.

Questions Addressed:

- What is the role of metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with special attention to liver function?

- What liver function markers are associated with cognitive dysfunction and the amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration (A/T/N) biomarkers for AD?

- What might be the reason/s underlying the associations found between serum liver function markers, imaging results, and cognitive dysfunction (including AD)?

Study Synopsis and Perspective:

Altered liver enzymes were consistently associated with cognitive changes and AD in a large observational study of older adults.

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratios were significantly increased in people who had cognitive impairment and AD biomarkers for A/T/N compared with cognitively normal people, reported Andrew Saykin, PsyD, of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, and Rima Kaddurah-Daouk, PhD, of Duke University, and co-authors in JAMA Network Open.

Lower levels of ALT also were associated with poor cognitive performance and some markers of AD, and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels also were significantly associated with poor cognition.

The study “is the most comprehensive analysis to date linking blood biomarkers — in this case, clinical lab tests of liver function — with cognition, MRI measures of brain structure, and molecular tests of Alzheimer’s associated amyloid and tau proteins,” Saykin told MedPage Today.

“The significance of these associations is that they underscore the importance of connecting peripheral and central biological processes,” he said. “Now that we know they are related, new questions emerge: How do central and peripheral processes evolve over time? How do longitudinal changes in these blood analytes relate to clinical, cognitive, and neural changes? What are the causal directions and pathways? Most importantly, are there medications or lifestyle interventions that influence liver function that might reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias?”

The study was conducted for the Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium(ADMC), part of the National Institute on Aging’s Accelerated Medicine Partnership for Alzheimer’s Disease. ADMC researchers are “trying to map global metabolic changes across the trajectory of the disease,” said Kaddurah-Daouk, who heads the consortium. “They are measuring thousands of chemicals in the blood to define when changes in metabolism happen and the mechanisms that lead to metabolic failures.”

In their analysis, the researchers looked at five serum-based liver function markers that had been measured from 2005 to 2013 in 1,581 Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants: total bilirubin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, ALT, and AST.

Primary outcomes included a diagnosis of AD, composite scores for executive functioning and memory, CSF levels of amyloid-β and tau, brain atrophy measured by MRI, brain glucose metabolism measured by fludeoxyglucose F 18 (18F) PET, and amyloid-β accumulation measured by [18F] florbetapir PET.

Participants were an average age of 73, and 56% were men. The study population included 407 cognitively normal older adults, 20 with significant memory concern, 298 with early mild cognitive impairment, 544 with late mild cognitive impairment, and 312 with AD.

The researchers found that individuals with elevated AST:ALT ratios were more likely to have an AD diagnosis (OR 7.932, 95% CI 1.673-37.617; P=0.03) than cognitively normal adults were. Increased AST:ALT ratio was also linked to poor cognition, lower CSF levels of the 42-residue form of amyloid-β, increased amyloid-β deposition, higher CSF levels of phosphorylated tau and total tau, and reduced brain glucose metabolism.

In addition, levels of ALT were significantly decreased in AD patients compared with cognitively normal individuals (OR 0.133, 95% CI 0.042-0.422; P=0.004). Lower levels of ALT also were associated with increased amyloid-β deposition, reduced brain glucose metabolism, greater brain atrophy, and poor cognition.

In addition to changes in ALT levels and AST:ALT ratios, elevated alkaline phosphatase levels also were significantly associated with poor cognition.

“While we have focused for too long on studying the brain in isolation, we now have to study the brain as an organ that is communicating with, and connected to, many other organs that support its function and that can contribute to its dysfunction,” Kaddurah-Daouk told MedPage Today. “Hence, the emerging concept that Alzheimer’s might be a systemic disease that affects several organs, including the liver, and that these changes in the body can lead to metabolic problems in the brain needs to be more fully explored.”

Diet, gut bacteria, lifestyle and environmental factors, and genes “all can contribute to failures in our metabolism,” she pointed out. “These failures can affect peripheral organs and also the brain.”

Study limitations, the researchers noted, included the observational design of ADNI, which limited the ability to make assumptions about causality, and the relationship between liver enzymes and AD still needs to be studied prospectively. In addition, the investigators did not adjust for alcohol consumption and used γ-glutamyltransferase as a surrogate, but that marker generally indicates long-term, not episodic, heavy drinking.

Key findings remained significant after adjusting for γ-glutamyltransferase and statin use, the team said. “However, given the associations with liver function measures and A/T/N biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease, it appears that liver function may play a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, but limitations should be taken into account before further extrapolating our findings … Liver enzyme involvement in AD opens avenues for novel diagnostics and therapeutics.”

Source reference: JAMA Network Open 2019: 2(7): e197978

Study Highlights: Explanation of Findings

The researchers explained that they conducted the study in the context of increasing evidence pointing to the role of liver function in the pathophysiology of AD. “The liver is a major metabolic hub; therefore investigating the association of liver function with AD, cognition, neuroimaging, and CSF biomarkers would improve the understanding of the role of metabolic dysfunction in AD,” the team wrote.

The cohort study, which tracked liver function in 1,581 older adults, found that elevated AST:ALT ratios were associated with AD diagnosis, poor cognition, lower CSF levels of amyloid-β 1-42, increased deposition of amyloid-β, higher CSF levels of phosphorylated tau and total tau, lower brain glucose metabolism, and greater brain atrophy.

“Consistent associations of serum-based liver function markers with Alzheimer disease biomarkers highlight the involvement of metabolic disturbances in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer disease,” the investigators said.

They explained that due to the study’s prospective cohort design, it is not possible to draw any conclusions regarding causation and liver dysfunction. ALT and AST levels, among other biomarkers, are also used to determine general liver injury, and are associated with cardiovascular as well as metabolic diseases, which are themselves risk factors for AD and cognitive decline. However, until this study, there have been only a few studies linking peripheral biomarkers of liver function to central biomarkers related to AD and structural brain atrophy, the team noted.

Specifically, some of their novel findings included the following:

- Higher ALT levels were significantly associated with reduced amyloid-β deposition in the bilateral parietal lobes

- Increased AST:ALT ratios were significantly associated with increased amyloid-β deposition in the bilateral parietal lobes and right temporal lobe

- Higher AST:ALT ratios were associated with higher CSF p-tau values, which showed consistent patterns in the associations of CSF amyloid-β 1-42 or p-tau levels and brain glucose metabolism

- Higher ALT levels were associated with increased glucose metabolism in a widespread pattern, especially in the bilateral frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes

- Higher AST:ALT ratios were significantly associated with reduced glucose metabolism in the bilateral frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes

- Higher ALT levels were significantly associated with larger cortical thickness in the bilateral temporal lobes, which showed consistent patterns in the associations of brain glucose metabolism

Discussing potential mechanisms whereby liver function enzymes affect cognition, the authors noted: “Disturbed energy metabolism is one of the processes that may explain the observed lower levels of ALT and increased enzyme ratio in individuals with AD and impaired cognition. This finding is concordant with our observation that increased AST to ALT ratio values and lower levels of ALT showed a significant association with reduced brain glucose metabolism, particularly in the orbitofrontal cortex and temporal lobes.”

Brain glucose hypometabolism is an early signal of AD and cognitive impairment; ALT and AST are key enzymes in the liver’s gluconeogenesis and production of neurotransmitters, including glutamate, needed in maintaining synapses, added Saykin, Kaddurah-Daouk, and colleagues. “The liver-brain biochemical axis of communication should be further evaluated in model systems and longitudinal studies to gain deeper knowledge of causal pathways.”

Reviewed by Dori F. Zaleznik, MD Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine (Retired), Harvard Medical School, Boston

Primary Source

JAMA Network Open

Many diabetics don’t know you can buy inexpensive, OTC insulin in U.S.

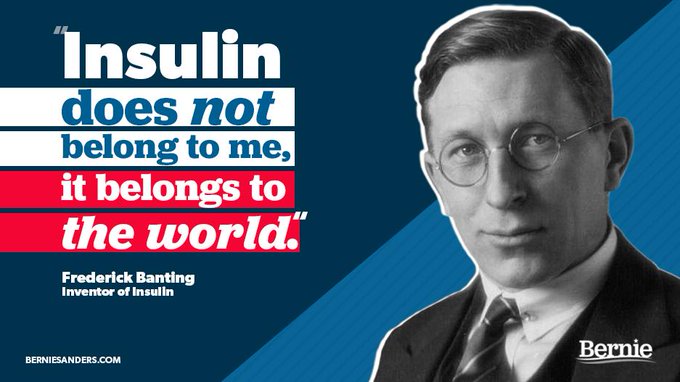

A trip to Canada [to buy cheaper insulin] celebrates the achievement of Dr. Banting and his colleagues who discovered insulin nearly a hundred years ago. But for most patients with diabetes, a trip to Walmart is a better way to save money.Dr. Robert Misbin, retired FDA scientist, to SharylAttkisson.com

Important information about insulin cost and availability comes from a retired FDA scientist who reviewed several modern insulin treatments for diabetes.

Inexpensive, safe and effective insulin is available for purchase in the U.S. over the counter without a prescription.

Insulin prices have been skyrocketing, and diabetic patients are said to sometimes ration their prescription insulin as a result.

A recent tweet from presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vermont) raised concerns about the health impact of high cost insulin. “Americans are dying because drugmakers like Eli Lilly charge $300 for a vial of insulin,” wrote Sanders. The following day, Sanders traveled to Canada to purchase insulin at a lower cost to try to demonstrate the need for price reforms in the U.S.

The inventors of insulin sold the patent for just $1 so it would be available to all.97 years later, Americans are dying because drugmakers like Eli Lilly charge $300 for a vial of insulin. Tomorrow I will be joining diabetics to buy insulin in Canada for one-tenth the price.

5,957 people are talking about this

However, Dr. Robert Misbin says it’s not necessary to go to Canada, as Sanders suggests. Inexpensive options are available to any patient “over the counter” without a prescription in the U.S.

Dr. Misbin is a retired FDA scientist who conducted the original FDA medical review of the newer, synthetic “analog” insulins Humalog in 1996-97 and Lantus (glargine HOE 901) in 2000. He says they can be more convenient for patients than older, over the counter “human” insulin such as Humulin, but are also more expensive.

I do not accept the idea that people are dying for lack of expensive insulin analogs. Many patients get better control with the analogs but the older preparations work quite well. Humulin and Novolin are human insulin, identical to what comes from the pancreas. Before 1997, there were no analogs. According to Walmart’s website, it sells a vial of Novolin for $25 without a prescription.Dr. Robert Misbin, retired FDA scientist, to SharylAttkisson.com

The big escalation in price of insulin came after the introduction of synthetic or “analog” forms of insulin beginning in 1997. According to Dr. Misbin, the analogs are much more expensive and not that much better except for convenience.

Convenience factors in because some of the new analogs can be injected immediately before a meal, in contrast to regular human insulin that should be injected 15 minutes in advance of a meal for best effect.

Also, long acting analogs can be given once a day. The older version of insulin is administered twice a day. Some patients and doctors also believe analogs are more predictable.

“Some patients claim the new insulins are better, but if one looks at the data–and I did that– there was really no difference in effectiveness between the old and the new,” says Dr. Misbin. “Of course, randomized trials do not allow for individual preferences.”

And that’s the important part amid the concern over cost: the “old” insulin is widely available over the counter for a fraction of the cost of the “newer” insulin.

Some patients already know this inside secret. Human insulin is available over the counter in every state except Indiana, according to Medscape.

Medscape notes Walmart sells its own brand of over the counter insulin, ReliOn (made by Novo Nordisk) for approximately $25 for a 10 mL vial.

Other over the counter human insulins, says Medscape, sold at other pharmacy chains, run approximately $152-$163 for a 10-mL vials [Novolin (Novo Nordisk) or Humulin (Eli Lilly).

That’s considerably less expensive than newer, prescription insulin analogs such as lispro (Humalog, Eli Lilly), aspart (Novolog, Novo Nordisk), and glargine (Lantus, Sanofi), according to Medscape. The medical publication conducted a survey and estimates Walmart sells 18,000 vials of over the counter insulin daily.

Dr. Misbin says the FDA knew that approval of synthetic analogs of insulin would eventually lead to higher prices for patients. “We knew this would increase the cost of this form of treatment,” he remarked. The FDA did not have the authority to take cost into account when determining whether a drug should be approved as safe and effective.

“I think there could be a lot of change if more people were aware” of the availability of the over the counter insulin,” says Dr. Misbin.

Dr. Misbin says it is true that the inventors of insulin sold the patent to the University of Toronto for just $1 so that insulin would be available to all. He points to additional background as reported in “The history of Insulin” by Michael Bliss:

Indeed, Fred Banting refused to be on the original [insulin] patent feeling it was contrary to the Hippocratic oath he swore as a physician. The original Canadian patent was taken out by the chemist James Collip and Charles Best (who was still only a medical student). The patent was taken on by the University of Toronto, which later entered into arrangements with Eli Lilly to manufacture and market insulin in the USA.

Other findings from Medscape’s Miraim Tucker:

- Findings from surveys of nearly 600 US pharmacy chains in 2018 were published online February 18 in JAMA Internal Medicine by Jennifer N. Goldstein, MD, assistant program director of Internal Medicine at Christiana Care Health System, Newark, Delaware, and colleagues.

- The results showed that OTC insulin is sold more commonly at Walmart than at other pharmacy chains and that inability to afford co-pays for prescription insulin was noted as a common reason for purchase, particularly at Walmart pharmacies.

In Medscape’s article, experts caution use of over the counter insulin without medical supervision is “never recommended and could be very dangerous.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)