A new breed of online health-care startups is testing the boundaries of medical marketing, advertising prescription drugs for unapproved uses to college students with stage fright and men seeking to improve their sexual performance.

Hims Inc. markets sertraline, a generic version of the antidepressant Zoloft, to treat premature ejaculation. “Ending the bedroom fun a little too soon? Sertraline can help treat premature ejaculation so sex can last longer for both you and your partner,” the company said in an Instagram post.

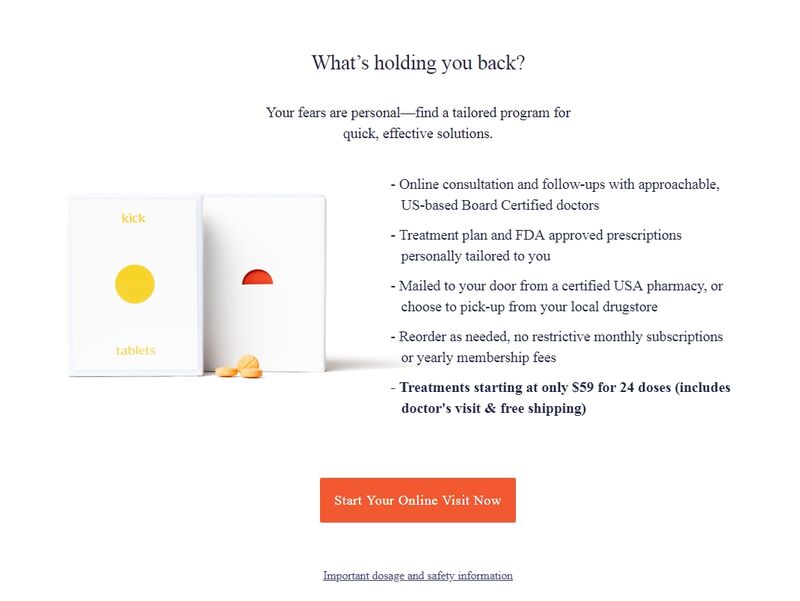

Kick Health, another startup, sells the blood-pressure drug propranolol to treat anxiety, an off-label use. Kick says on its website that the pill can help you “nail the interview,” “speak confidently,” or even “just say hi.”

While some doctors will prescribe the two drugs for those uses, and both drugs have clinical data showing they may help some patients with the conditions, sertraline and propranolol haven’t been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for those purposes. With some of their ads, marketing copy and social media posts, the startups are pushing the boundaries of how prescription drugs can be marketed, according to pharmaceutical and legal experts interviewed by Bloomberg.

The Forhims website.

Source: forhims.com

“It’s not clear to me that this is totally kosher,” said Patricia Zettler, a former FDA lawyer and a law professor at Georgia State University.

Under FDA rules, pharmaceutical companies and distributors can’t make claims that haven’t been approved by drug regulators. Known as off-label marketing, the practice has led to hundreds of millions of dollars in fines and legal settlements from companies. Doctors, however, can legally prescribe whatever they want off-label — including using a blood-pressure drug to treat nerves, or an antidepressant for premature ejaculation — even if the FDA hasn’t cleared those uses.

After a new fundraising round in January, San Francisco-based Hims was valued at about $1 billion, according to Pitchbook, a venture capital research firm. Kick, which is also based in San Francisco, declined to say how much it had raised. The companies said that their businesses are platforms, and that it’s up to the doctors they work with to make medical decisions about the drugs they sell.

A Gray Area

The rules for U.S. drug marketing were written at a time when online prescription drug startups didn’t exist. Hims and Kick don’t make drugs, but instead charge patients for a consultation with a doctor through an app or online. They then sell the drug, often a less-expensive generic, to the patient. Their marketing, with cheeky ads on social media and public transportation, touts a variety of pharmaceutical and wellness treatments for men and women, with the ease of never having to step into a medical office.

Whether Hims and Kick are breaking drug-promotion rules may depend on whether they’re selling the services of a physician who can prescribe a drug as they see fit, or whether the startups are directly advertising a prescription drug that comes with benefits and risks.

The Gokick website.

Source: gokick.com

“If you have this third party that has nothing to do with the manufacturer then they can say almost whatever they want,” said Nathan Cortez, a health law expert at Southern Methodist University. But the startups could still get in trouble for things like exaggerating the benefit of a drug, or downplaying the risk. “Legally, there is a gap here and the gap has always been a problem. The gap is between who can who can regulate the practice of medicine, and who can regulate products and manufacturers.”

Kick makes a familiar tech-industry argument: They don’t make the medicine; instead, they’re a platform to connect a service (doctors, who can prescribe what they want) to customers (patients).

“We never touch the drugs. We’re not a distributor,” Kick founder and Chief Executive Officer Justin Ip said in an interview. “I wish it was 100 percent crystal-clear. We’ll see how things go, but we think we’re on the right side of the law. If not, we’ll be happy to adjust.”

The FDA declined to comment on Hims’s and Kick’s marketing. “The FDA works to ensure that prescription drug information communicated by these entities is truthful, non-misleading and accurate. Generally, FDA monitors company promotion and communications regarding prescription drugs through its surveillance operations,” said Nathan Arnold, an agency spokesman.

For patients, the distinction between advertising medical care from a doctor and marketing a drug may not be quite so clear. Hims’s website features a black button urging men to “Buy Propranolol.” Its sister company, which markets to women under the brand Hers, also promotes the drug, and has faced some blowback.

“Nervous about your big date? Propranolol can help stop your shaky voice, sweating and racing heart beat,” Hers said in one social media post. In a March 12 follow-up post, the company said it had pulled the message. “We’ve permanently removed that ad and are working with our medical team to ensure that all copy is safe and accurate for the consumer moving forward.”

Hims said that it’s a platform for doctors, who make the judgment about when it’s medically appropriate to prescribe, not the company.

“Only a licensed physician is in the position to know the risks and benefits of a certain medication and whether it’s the best option for a patient,” Hims said in a emailed statement. “We created the hims and hers platform to help make that conversation possible without judgement or stigmatization.”

Beta-blockers impede the effects of adrenaline, making the heart beat more slowly and reducing blood pressure. That also has the effect of stemming the physical symptoms of anxiety, making the drugs a popular prescription for some people with high-pressure jobs, like concert musicians.

But without conducting clinical trials and gaining FDA approval for the drug to treat anxiety as well, drugmakers aren’t allowed to tout its ability to treat that condition. Side effects of propranolol can include dizziness, weight gain, an irregular heart beat and difficulty breathing, according to the FDA’s label for the medicine.

Zoloft and its generic equivalents belong to a class of drugs known as serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. They’ve been approved to treat depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and other mood disorders. While there’s clinical data showing they can help with premature ejaculation, the FDA hasn’t approved the use. Zoloft also comes with a warning on its label, saying that in younger patients it can bring on suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Digital Doctor’s Office

Outside health care, other startups have pushed legal or regulatory boundaries while creating new industries — and won. When Airbnb Inc. and Uber Technologies Inc. began offering lodging and transportation, respectively, both faced efforts by regulators to curtail their businesses even as their popularity grew with consumers. Both are expected to IPO at multibillion-dollar valuations this year.

Unlike Kick, which for now only sells propranolol, Hims and another well-funded startup, Roman Health Medical LLC, offer a variety of treatments for many conditions, and have framed themselves as digital doctors’ offices where multiple treatments are available. Roman in its marketing copy advertises treating specific conditions, while Hims more often advertises specific drugs, sometimes noting that the usages are “off-label.”

Sildenafil from Roman

Source: Roman

“If they were saying, ‘We’ll connect you to the best doctors to treat social anxiety, that’s one thing,” said Zettler, the law professor, referring to Kick. “It’s another to say, ‘We’ll connect you to a doctor to prescribe a specific drug, and ship you that drug.’”

In a statement, Roman said that it doesn’t charge patients for a drug before a physician consultation.

Selling a Disease

Nicolas Terry, the director of the Hall Center for Law and Health at Indiana University’s law school, said brands like Kick, with their sleek approach to selling medication, run the risk of “disease mongering,” especially for conditions as common as being nervous about a date or giving a presentation in college.

Kick’s website pitches propranolol as the “insider’s edge to performing anxiety,” and “prescription-strength confidence.” On Hims’ website for propranolol, an image of a bearded, tattooed man reclining in a chair holding an apple appears alongside text saying the drug can help get your mind “in game time mode” when “your body is somewhere else completely.” Hers’s website for propranolol suggests women could take it for help “manifesting your badassery.”

“There is cause for concern here,” Terry said. “What they do is suggest a normal pathology is a sickness.” Terry said he is worried such an approach doesn’t make customers aware of all the risks associated with a prescription.

“Propranolol is old and dirt cheap, but this is an exaggeration of benefits and failure to disclose risk,” he said.

Robert Attaran, a professor of cardiology at the Yale School of Medicine, is listed as an adviser to Kick on the company’s website and consulted with the company before it launched. He said beta blockers are generally safe, low-risk drugs, especially at the doses given for anxiety. But Attaran stressed the need for any online patient to get a full evaluation before receiving a prescription to make sure it’s safe.

“Various technologies are emerging to cut out the middlemen in medicine. It’s a trend that’s coming right or wrong,” Attaran said. “But it can be a slippery slope.”

The easier it becomes for patients to get drugs, he said, the greater the chance something like an underlying medical condition is missed. He said his concerns are greater for a drug like Zoloft than beta blockers.

As antidepressants like Zoloft have become popular as a way to treat premature ejaculation, some doctors have raised concerns that the potential side effects aren’t worth the risk. One 2015 study of other related drugs used for the condition found that 70 percent of men stopped using one medicine, dapoxetine, citing side effects and limited efficacy.

Zettler, the former FDA attorney, said other aspects of these companies’ marketing may also be problematic.

“Is that Instagram ad truthful and non-misleading? If it’s talking about benefits of the drug, it should also should be talking about risks,” she said. “It’s not exactly clear whether in these quasi-direct-to-consumer models if their very beautiful marketing is complying with all of the rules around prescription drugs.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.