What started with a few dozen dead pigs in northeastern China is sending shock waves through the global food chain.

Last August, a farm with fewer than 400 hogs on the outskirts of Shenyang was found to harbor African swine fever, the first ever occurrence of the contagious viral disease in the country with half the world’s pigs. Forty-seven head had died, triggering emergency measures including mass culling and a blockade to stop the transportation of livestock. Within days, a government notice proclaimed the outbreak “effectively controlled.”

It was too late. By then, the disease had literally gone viral, dispersed across hundreds of miles in sickened animals, contaminated food, and in dirt and dust on truck tires and clothing. Nine months later, the contagion has spread nationwide, crossed borders to Mongolia, Vietnam and Cambodia, and bolstered meat markets globally.

While official estimates count 1 million culled hogs, slaughter data suggest 100 times more will be removed from China’s 440 million-strong swine herd in 2019, the Chinese zodiac’s “year of the pig.” The U.S. Department of Agriculture forecast in April a decline of 134 million head — equivalent to the entire annual output of American pigs — and the worst slump since the department began counting China’s pigs in the mid 1970s.

Pig Out

China’s hog output is predicted to slide 20% in 2019 to a 17-year low.

“This is an unprecedented situation,” said Arlan Suderman, chief economist for INTL FCStone Inc., who has been analyzing commodity markets for almost four decades. “This will impact food prices globally.”

Like Ebola

The strain of African swine fever spreading in Asia is undeniably nasty, killing virtually every pig it infects by a hemorrhagic illness reminiscent of Ebola in humans. It’s not known to sicken people, however.

The harm to pigs is especially critical for China, with a $128 billion pork industry and the world’s third-highest per-capita consumption.

Pork Lovers

China’s 2017 per-capita pork consumption was almost triple the global average.

China’s hog herd may decline as much as 30 percent, said Juan R. Luciano, chief executive officer of Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., one of the biggest agricultural commodity traders.

“China will clearly need to import substantial amounts of pork and likely other meat and poultry to satisfy demand,” Luciano told analysts on an April 26 conference call. Chinese meat purchases may also boost sales of soybean meal, a source of livestock feed, in North America, Brazil, and Europe, he said.

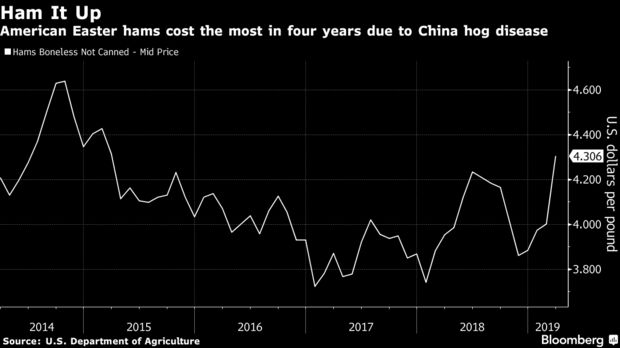

Wholesale pork prices in China are already 19 percent higher than a year ago, and have risen in the U.S. and EU after processors sent more of their product to China. The price of bacon in Spain jumped about 20 percent during March, while pork shoulders climbed 17 percent in Germany, according to Interporc, a Madrid-based industry group.

Needing Meat

China will boost its imports to plug a domestic pork shortage.

“The potential quantum of this is huge,” said Angus Gidley-Baird, a commodities analyst with Rabobank in Sydney. “It’s the biggest thing to affect the animal-protein market this year, and will probably have a lasting effect for a number of years. It will move markets and possibly influence geopolitical situations.”

The rally has spread to other meats. Australia’s beef exports to China surged 67 percent in the first quarter. In Brazil, shares in meatpackers such as JBS SA and Minerva SA have soared amid optimism of stronger sales to China.

Contagion Effect

Increased Chinese meat imports will result in higher food costs that impact on economies across the globe. The extent of those ripple effects depends on how quickly the epidemic can be stopped. Official data show a slowdown in the number of pigs affected since late 2018, supporting the government’s assessment that the disease is “under effective control.”

Analysts from Morgan Stanley to Citigroup Inc. to the U.S. Department of Agriculture aren’t convinced that the disease isn’t still spreading.

Pork is the largest component of China’s consumer price basket, and its influence on other meat prices means that a doubling of pork prices in China would boost the country’s inflation by 5.4 percent, all other things being equal, according to Citigroup, which is forecasting a 2.6 percent inflation rate for the country in 2019.

The Chinese government will likely treat any pork-related inflation as an extraordinary event separate from general cost increases, said Liu Ligang, chief China economist at Citigroup. in Hong Kong. Still, if rising pork prices elevate inflation beyond a ceiling rate of 3 percent, it could constrain the People’s Bank of China from taking aggressive measures to boost the economy.

Supply Shock

“The more field studies people tend to do, the more fear they tend to have,” Liu said. “This is a supply shock, not a demand shock, and as a result this could be transitory. But this could be a prolonged supply shock given the severity of the disease.”

The epidemic could have political repercussions as well. Xi Jinping may want to finalize trade negotiations with U.S. President Donald Trump to both ease the importation of much-needed pork, poultry and beef supplies, and to enable Chinese lawmakers to focus solely on quelling outbreaks, said INTL FCStone’s Suderman.

Officers inspect pork products intercepted from high risk areas of African swine fever.

Photographer: Costfoto/Barcroft Images via Getty Images

The contagion is also highlighting the urgent need for government investment in outbreak preparedness, said Amanda Glassman, chief operating officer at the Center for Global Development.

African swine fever in China shows that “animal and human disease surveillance systems are not working as well as they should,” she said. “This should concern everyone given that the potential economic impact of large-scale outbreaks is huge.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.