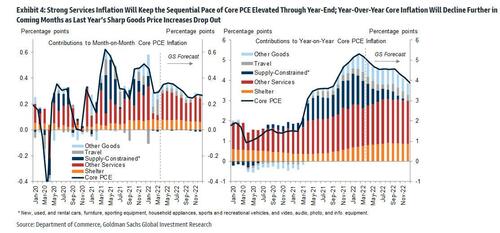

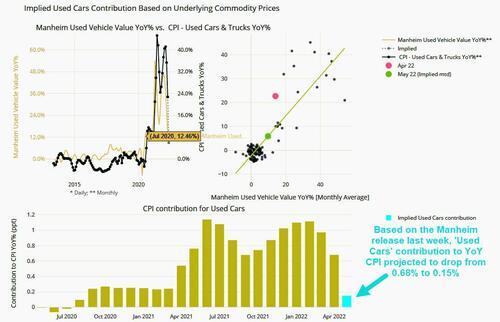

In recent days we have speculated that while food and energy prices are likely set to keep soaring for many months ahead, core prices especially among goods have likely peaked...

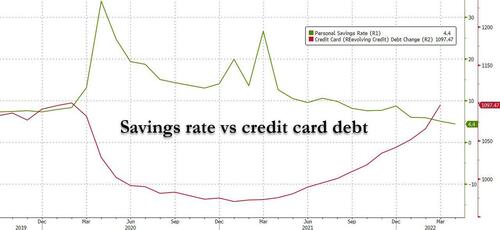

... and will trend lower over the next year, especially if our thesis that the US is about to experience a major downside shock to the labor market - one which crushes US consumer whose savings rate just hit a 14 year low as the amount of credit card debt goes vertical

... materializes. Finally, all of this takes place as markets have fallen sharply amid sharply higher inflation and as growth expectations slump, leading to further deceleration in the inflationary impulse.

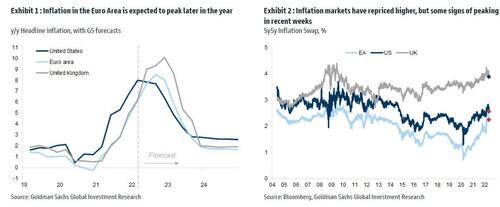

That said, it's not just us who thinks that core (if not headline, because as noted above both food and energy inflation will continue to rise for a long time) inflation has peaked: as Goldman economists write this weekend, "US inflation has probably already peaked and expect European inflation to peak in the next 2-3 months (see Exhibit 1). Even in the UK, where the inflation spike has been especially sharp, we think core inflation has peaked in April and headline will do so in October once the Energy price cap rises"

To be sure, the impact of the rate tightening cycle, growth slowing and the falling out of the Y/Y numbers of some sharp rises from 2021 (autos prices for example) should all help to bring down the pace of inflation.

In addition, the Y/Y growth of energy prices is moderating and semis supply is starting to ease. It is also notable that market implied inflation has started to moderate too.

Overall, Goldman thinks headline inflation is likely to be peaking, which also prompts the Vampire Squid to ask "could this be a catalyst to support a turn equities?" Their answer: "it is probably more a necessary than sufficient condition."

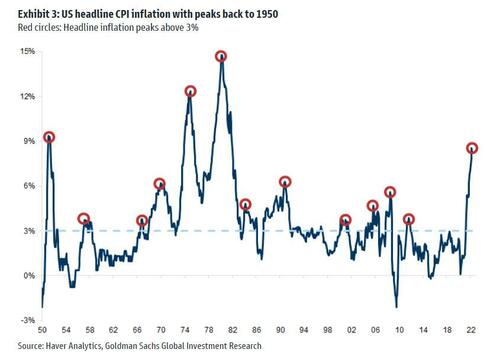

Looking at US history, Goldman identified the peaks in headline inflation going back to 1950 (the bank only took clear peaks above 3% yoy inflation and found 12 peaks above 3% prior to today.)

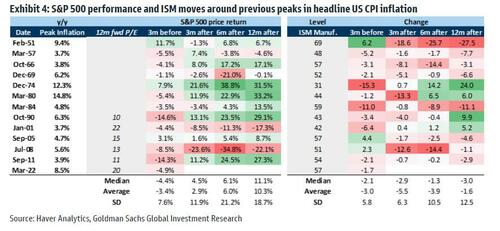

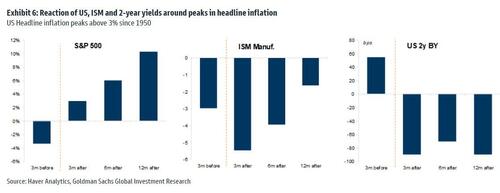

In terms of what to expect in markets as inflation peaks, Goldman shows in the next chart that the market usually falls in the run up to the peak in headline inflation, just as we have seen in recent months. But after the peaks, there is a little more variance and on average the market does recover.

Of course there are times when this didn’t happen. Goldman admits that the peak in inflation might be helpful but equities really need other supports, especially if investors fear a sharper downturn. Among these are:

The economy: Interestingly the peak in inflation is often followed by a continued weak economic outlook with the ISM continuing to fall as was the case in the 50s/60s after the peak in inflation and in the mid-1980s. But as Goldman's economists note, there are some exceptions – post the late 1974 peak in inflation, the market recovered sharply and the economy did too with the ISM up 24pts in the 12 months from December 1974 (from a low of 31). The early 1990s also saw a strong rise in the ISM post the peak in inflation. Dec-74, Mar-80 and Oct-90 peaks in inflation were all good times to buy the market but they were also at or around economic troughs. There were three times when it would have been a clear mistake to buy equities at the peak in inflation: Dec-69, Jan-01 and Jul-08. In two of these cases, it was because the economy was at or about to enter recession (1969 and 2008). And while a recession after the recent inflation peak is very much assured, the $64 trillion question is what will the Fed do to offset it?

Valuation: In January 2001, the market continued to fall even after the peak in inflation as the starting point for valuation was still high. In a different case, in September 2011, inflation peaked and again it was a good entry point, but this was not because the economy was about to turn, but more because valuations were low. The forward P/E on S&P 500 was 11x in late 2011.

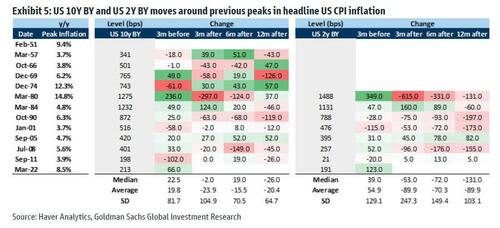

Rates: Another support for the market in the post-inflation-peak period has been falling rates – both long and short rates have typically declined – but especially at the shorter end of the curve: on average in the 12m after the peak in inflation the 2-year yield has been down 90-130bp (Exhibit 5).

October 1990 is a good example of all three supports - the market rose 30% in the subsequent 12-months post the peak in inflation with the ISM rising almost 10pt and the 2-year yield falling almost 200bp. Still, as Goldman again reminds readers, "the starting point for valuation was just 11x forward EPS. A very different set-up from the one we have today."

Looking across the Atlantic, the profile of European stocks is similar to the US around peaks in inflation: European markets are weak in the months preceding the peak in inflation but on average rise after inflation has peaked. Indeed, European equities typically outperform as US inflation peaks (as shown below). This may be a function of the higher beta of European equities, the UK with a lower beta tends not to outperform after inflation peaks. The fact that the UK has a large share of commodity stocks might also account for its relative resilience in the run up to inflation peaking as well.

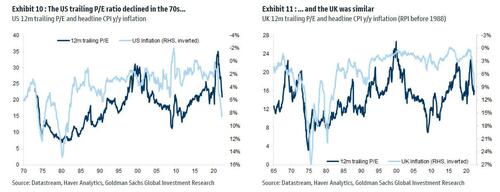

To be sure, periods of higher inflation are generally associated with lower equity valuations, which is why Goldman warns that even if inflation does come down from the peaks, assuming it stays sticky and high and is higher than last cycle then it's likely that valuations - especially in the US - won't rise to the levels we saw last cycle when inflation was lower and less volatile. This is a similar point BofA just made in an earlier post. Indeed in the 1970s the average PE in the US was 12.0 and in the UK 11.7 (based on trailing earnings). Of course, if we get a rapid reversal and inflation quickly mutates into deflation, then all bets are off.

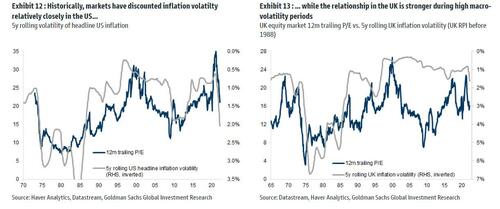

It's not just the level of inflation but the volatility of inflation too - when inflation is more volatile (spikes followed by sharp falls as growth slows) this can be even worse for equities. The uncertainty both in terms of monetary policy and margin setting make high inflation volatility generally difficult for equities to digest. The tightness of both energy and labor markets makes not just high inflation more likely but also more volatility and bigger spikes (as we have seen in gas prices for example).

With all these caveats in mind, Goldman asks, rhetorically, If inflation peaks who has most to gain?

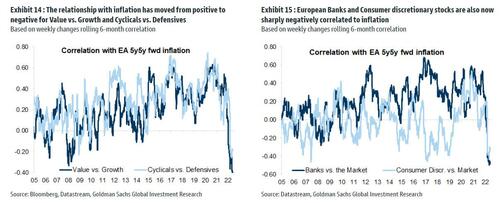

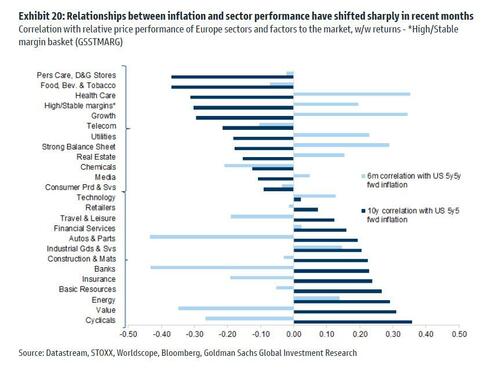

It answers by pointing out that relationships with inflation are not stable over time: in the last decade, higher inflation was associated with cyclicals and value outperforming, and low inflation - which was main concern in Europe until relatively recently - was associated with underperformance. But now relationships have reversed and higher inflation has been damaging to cyclicals and value stocks (outside of commodities). This is because it has been seen as increasingly supply-side rather than demand driven and because ultimately it provides a speed-limit to growth and prevents CBs from loosening even in the event that growth is slowing. In that sense, inflation peaking should be good for cyclicals. Banks and Consumer discretionary stocks are also now sharply negatively correlated to inflation.

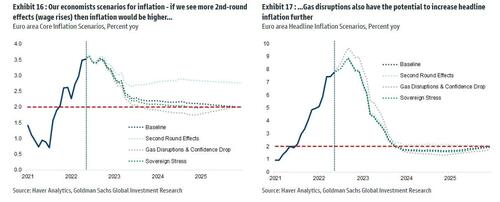

Much depends on whether the inflation peak is seen as marking an end to the sharply rising rate expectations we have seen in recent months and ultimately providing room for CBs to loosen policy should they need to. The uncertainty around the potential paths for inflation and the likelihood of it remaining sticky and high probably mitigate against equities rallying sharply. As Goldman shows below, the bank's economists model various scenarios for inflation and in most cases - unlike just a few months ago - inflation remains sticky and high, which is precisely why we are confident in our view that the not too distant future, inflation will be replaced with deflation.

Here Goldman also notes that another consideration is how much of the higher inflation we are seeing now is discounted, and cautions that consumer discretionary names remain vulnerable even as inflation moderates. While stock valuations have fallen, demand is likely to be hit by the persistent and sticky inflation and its impact on real wage growth.

As the bank shows in the charts below, considering the pace of inflation and the consequent sharply negative real wage growth, the hit to consumer areas that Goldman has been looking at have seen so far still looks relatively modest. While we think that is rapidly changing in the US, where we just saw a historical plunge in new home sales and the abovementioned record jump in credit card debt coupled with tumbling savings...

... other places are looking somewhat better: consider the UK, where the available cash flow for households to spend on non-essentials (food/energy/rent) is set to decline in 4Q22/1Q23, yhet the high level of savings and still capped energy costs is cushioning consumers now the cap is set to rise further in October, higher rates will slowly feed through to higher mortgage payments and finally households will have used more of their savings by late this year/early next.

With all that in mind, Goldman continues to recommend four areas in Europe: strong balance sheets, High & Stable margins and companies with exposure to a structural rise in Capex and/or government investment. Nonetheless, the bank is cautious on Consumer areas of the market and while falling inflation will be helpful, it remains of the view that "discretionary spend will take a sharp dip."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.