One of the few silver linings of this miserable pandemic is that the medical IQ of the average citizen rose considerably with a viral illness dominating the news cycle for a couple years. Among the once-dark topics of real importance now entered into the parlance of the general population are three letters which strike dread into the heart of any pediatrician come autumn: RSV.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus is a genuine killer, especially among the least and most antiquated members of our population. In infants, RSV infections lead to more hospitalizations and deaths on an annual basis than influenza or Covid-19. We have no treatment options beyond the uninspiring concept of “supportive care.” In that context, the search for a vaccine against RSV has been afoot for decades, plagued by misadventures including the utilization of an unstable protein and the challenges of immunizing a cohort — brand new babies — with marginal immune systems.

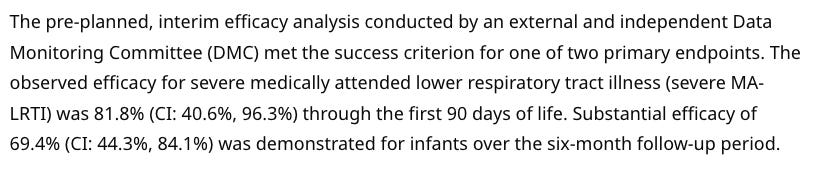

Now, at last, we have a genuine breakthrough in the form of a stable protein-based vaccine given to pregnant women in the third trimester, letting their immune systems create the antibodies and share them with their babies. According to Pfizer’s press release this week, the “RSVpreF” vaccine came through with an 82% reduction in severe RSV among infants in their first 3 months, dropping moderately to 70% when expanded to the first 6 months. No safety signals among the 3700 or so pregnant women and their children were reported amongst those receiving RSVpreF, and this aligns with peer-reviewed data from their much smaller Phase 1 study.

A viable vaccine candidate for a severe disease emerging unscathed from its Phase 3 trials brought out some understandably enthusiastic headlines like this one:

I am mostly enthusiastic myself. However, before we assume that every pregnant woman will be lining up for their Pfizer RSVpreF shot come 2023, it’s worth a harder look.

For one, we don’t have the data, just a press release. While the vaccine efficacy against severe disease looks very good, it’s impossible to pick it apart with so little information provided. Our “data” from the release:

Nice numbers, but this was an interim analysis, and the FDA has let them stop the study short. Perhaps some regression to the mean would have happened with more time; maybe they have failed to adequately account for seasonal variation between placebo and vaccine groups; possibly those big confidence intervals mean that the true efficacy would really land at 50% with more cases. We just don’t know enough to vet those appealing numbers. Pfizer also didn’t tell us how they define “severe” disease; and a year into their trial, they switched their secondary (critical!) endpoint of RSV hospitalizations to 360 days from 180 days… and then inspired my suspicion by not reporting any hospitalization data, interim or otherwise, in their breathless press release.

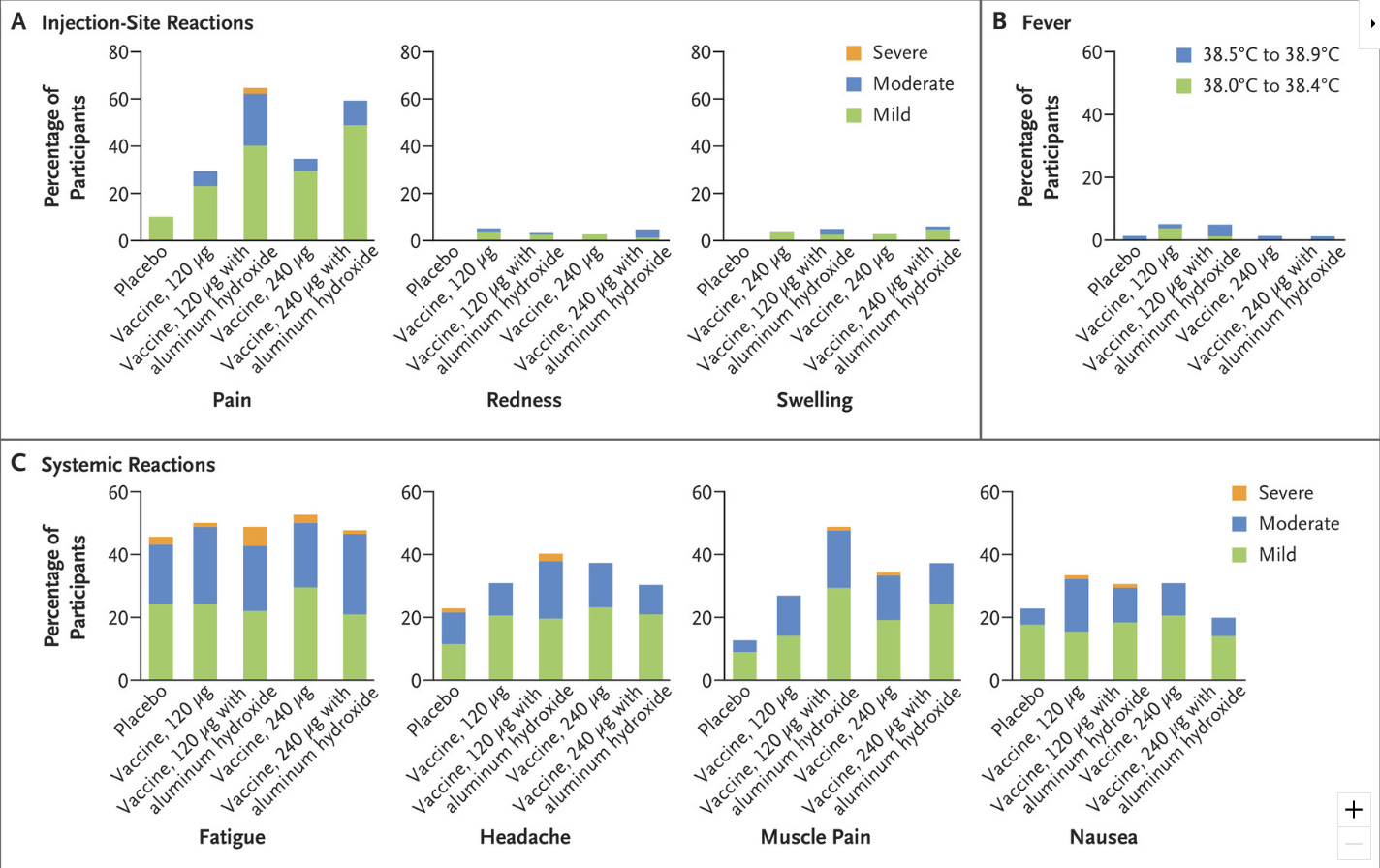

Then there’s safety. Again, we know that Pfizer is inclined to present their product in the best light, so peer-reviewed safety data is needed. Right now all we have in that regard is from the New England Journal of Medicine report on the 327 pregnant women in the phase 2b stage of the trial who received RSVPreF:

Again, it looks fine, although I quibble with studies finding >40% of placebo participants reporting systemic symptoms; when queried enticingly enough, half of us might recall a headache or some fatigue the day after our placebo shot, and that can bury a difference in real adverse reactions compared to the vaccine group. My primary concern, though, is that there is some biological plausibility around strong immune responses causing problems in a fetus given the complexity of our immune systems during pregnancy. While I suspect studies like this one from Norway, which found a 40% increase in autism among children of women who experienced a fever during their pregnancy, are undermined by confounding — fevers impairing fetuses strikes me as a big miss on the part of Evolution, and I don’t believe Charles Darwin made a lot of mistakes when he created humans — I take seriously any safety signal in interventions applied to pregnancy.

The flashing red “PROCEED WITH CAUTION” light you see is not under the Pfizer banner, however; it’s from their competitor’s maternal RSV vaccine. GlaxoSmithKline has trialed their own attempt at a protein subunit vaccine to trigger antibodies against the stable form of the RSV fusion (“F”) protein needed to enter our host cells; it has succeeded in its trials in adults >60 with an adjuvant to boost immune response, but the trial for the unadjuvented version for pregnant patients was stopped cold in February 2022 due to undisclosed safety concerns. Ouch:

GSK’s “GRACE” trial was about triple the size of Pfizer’s “MATISSE” maternal trial (yes, they really called it “MATISSE,” and their trial for older adults is “RENOIR” — ahem, I only report the news). What happened? If MATISSE had been larger, would a similar signal have been picked up? I don’t know enough about the differences between these two candidate vaccines — or vaccinology in general — to draw any conclusions, but since both vaccines aim to trigger an antibody response to the same F protein, it seems plausible they could share adverse effects. I’d rather they hadn’t stopped trial enrollment early in MATISSE; bigger is better when it comes to trial size at finding safety signals. At the least, some public discussion of why Pfizer’s RSVpreF is fine in pregnant women, while GSK’s RSVPreF3 is untouchable, would go a long way to reassure me. As far as I can tell, there has been none.

To be clear, though, I would be surprised if untoward maternal or fetal outcomes so problematic as to sink Pfizer’s new vaccine would go unnoticed in a study with over 3500 vaccine recipients. Professional skeptics will point out that no new vaccine has ever been licensed for use during pregnancy as just cause to demand mountains of safety evidence. While that claim might be true, we have been recommending influenza and Tdap immunizations during third trimester pregnancy for years, with the same concept Pfizer is now harnessing. Newborn infants don’t have a mature immune system in their first months; they rely on maternal antibodies crossing the placenta as well as in breast milk. (This is why our practice makes house calls for the first two months of our newest patients; physician waiting rooms are not an ideal milieu for the youngest lungs.) Sneaking maternal antibodies to influenza and pertussis, two truly threatening diseases to infants, into newborns via maternal vaccination has substantially reduced the incidence of both those diseases among infants, especially in the first two months. A huge observational Kaiser study reviewing over 400,000 live births looked at whether any infant all-cause hospitalization or death signal correlated with these vaccines; there was none:

However, we’re not just looking for absence of harm. We want to see compelling benefit. That Kaiser study? Somewhat surprisingly, buried in the happy news of the lack of a safety signal, only a 3% (not statistically significant) reduction in hospitalizations for respiratory viruses was seen among infants born of maternal recipients of flu and Tdap vaccines. That’s why it is so important to run big randomized controlled trials when the opportunity presents itself (they were never, to my knowledge, done for Tdap in pregnancy, and I found only 3 small studies on maternal influenza vaccination from Nepal, Mali, and South Africa, which showed only a modest effect). Sometimes real life surprises us.

Hence, I wish the MATISSE study had been beefier, bigger and longer, instead of allowing Pfizer to hasten their application after an interim analysis. I do get the counterargument: every RSV season without a vaccine, we sit back and watch 1-2% of our infants in the U.S. get hospitalized with RSV. Yes, you read that right: whether based on large epidemiologic studies or a recent randomized controlled trial, 1-2% of newborns end up in the hospital with RSV in their first year of life! (I am grateful for my early-career ignorance that I did not know that as a new parent.)

Does that make a RSV a vaccine-worthy threat? I will put it this way: the world was paralyzed by Covid-19 and yet it took over 18 months before 2% of U.S. senior citizens had been hospitalized with Covid.

So, RSV is a problem worth solving. Since at least three-quarters of infant RSV hospitalizations occur in the first 6 months, that 70% reduction in severe disease provided by RSVpreF over 6 months is a meaningful improvement to the suffering of infants, and their parents, if it holds up to scrutiny. We don’t have overall numbers yet from Pfizer, so we cannot calculate useful things like absolute risk reduction; but if this vaccine drops RSV hospitalization rates from, say, 1.5% to 0.5% in the first 6 months of life, that’s 100 vaccinations to prevent a hospitalization. Most reasonable people would agree that’s a vaccine worthy of a sore arm or headache, and even the risk of yet-unknown rare adverse events.

Why, then, do I speak of tapping the brakes, over a few theoretical concerns for the reliability of Pfizer’s efficacy data, and possible missed safety signals? Because we are about to have an alternative to the RSVPreF: AstraZeneca and Sanofi’s joint long-acting monoclonal antibody against RSV, nirsevimab.

Nirsevimab is to RSV what Evusheld is to Covid-19. For those whose immune systems were unfit to make antibodies to Covid vaccines, we offered Evusheld, sketchy data or not. For wee babies, trying to vaccinate them directly with an RSV vaccine has been a struggle, from disaster in the 1960s, to failure with an adenovirus vector candidate in 2022.

Enter nirsevimab: a one-time monoclonal antibody infusion injected — not infused by IV, thankfully — into an infant before their first RSV season. (Note: if we keep having RSV seasons starting in mid-summer, this we will be made more difficult, but let’s presume order will be restored to the universe and RSV will again predictably strike the Northern Hemisphere as the autumn leaves begin to cover the ground.) No wonderful T-cells, just antibodies — but, of course, that’s the bulk of what mom can pass to fetus after a vaccine like RSVpreF, as well. For decades, we have been using the short acting RSV monoclonal antibody, palivizumab/Synergis, for pre-term infants, via monthly injections, with over 50% effectiveness at preventing RSV hospitalizations. Now, nirsevimab has come through its Phase 3 trial, applied to healthy and term infants, offering a reduction in RSV hospitalizations from 1.6% in the placebo group of about 500 infants to 0.6% of those 1000 or so given nirsevimab, a reduction of 62%. That’s actual hospitalizations, not Pfizer’s undisclosed definition of “severe disease”. Safety looked fine, with 1 in the 1000 vaccinated infants suffering an “adverse event of special interest,” presumably auto-immune in nature, although it was not deemed serious.

Hence, we will have a conundrum for the 2023-24 RSV season, if all goes as expected and both products get their FDA approvals. Vaccinate mothers with RSVpreF? Or prophylax their babies via nirsevimab? If you just go by the current data, or what we know of it, at least, it’s tempting to declare nirsevimab the winner by a nose. It also touts the advantage, for physicians who are squeamish about universally recommending new medical interventions, to limit their guidance to higher risk infants based on social context, health, or pre-term status.

I’m not so sure. One last thought on this comes from a piece I read this week, entitled, “There’s No Such Thing as a Free Med.” I agreed with most all of it, especially the concept that the author, Dr. Paul Fenyves, refers to as a “risk tax:” given that we rarely know the hidden harms in a medical intervention, especially a novel one, it’s wise to build into our risk-benefit calculus some unknown cost. For instance, we didn’t know for a long time that ciprofloxacin could cause you to blow out your achilles tendon, or that ibuprofen increases the risk of heart attacks. Physicians tend to only account for what we think we know when we dispense advice.

However, in the case of an RSV vaccine, there might be some “risk subsidies” — unknown aspects of giving this vaccine that promise more benefit than risk. While not studied specifically in the trials, there is a benefit to a mom in reducing her risk of a nasty respiratory virus late in pregnancy; and since prenatal visits swell to a weekly basis deep in the third trimester, that’s fewer other pregnant women (and possibly their offspring, too) in the waiting room and OB/GYN’s with whom to share RSV particles. Likewise other family members, especially meaningful if grandparents are in the house to help with baby. The evolutionist in me also appreciates that female humans have been getting exposed to antigens, forming antibodies to them and passing them along to their offspring since time immemorial; our system, presumably, is built for this. Pouring monoclonal antibodies into a baby? Not so much — I suspect the unknown costs will outweigh the unknown benefits there.

These are the sorts of questions we ought be asking ourselves as we approach our next RSV season, one in which we seem likely to be blessed with two useful options against the scourge of this virus. I lean towards the vaccine. I wish the FDA had made my counsel easier by insisting Pfizer complete their study. We should have all learned by now that even the appearance of cutting corners in the vaccine approval process will carry its own unknown costs.

https://doctorbuzz.substack.com/p/pfizers-rsv-vaccine-for-pregnant

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.