A pre-print from Wales largely unnoticed by the mainstream media shook up my Twitter circles this week, making the bold claim that despite being an observational study, its clever design showed causality between receiving a shingles vaccine and reducing the risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease. Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease is somewhere on my top 3 list of “things I wish modern science would accomplish,” so I consider this a big deal! So did others:

The question, of course, is whether such a bold claim actually holds up to scrutiny. Could vaccinating against the varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox for its initial infection, and shingles upon reactivation later in life, truly reduce the rate of Alzheimer’s Dementia by over 20%? I’ve been curious about this area of research for some years since stumbling across the work of Dr. Ruth Itzhaki, who has been banging the drum for the critical role of a different herpesvirus, herpes simplex, in causing dementia. The concept seems rather plausible; herpes simplex (like zoster) hides in peripheral nerves but can cross into the brain, especially as we age and immune defenses weaken. A chronic viral infection could indeed trigger the sort of “neuroinflammation” which is now commonly cited as a potential cause of all sorts of neurologic and psychiatric problems. Some of Itzhaki’s work even reveals indirect evidence of an association between the presence of herpes simplex and the tau proteins and amyloid tangles which mar the neurons of advanced Alzheimer’s patients.

If we can blame herpes simplex, why not its cousin, varicella zoster? Stem cell culture work by Itzhaki’s team found that zoster exposure did not directly trigger Alzheimer’s-type changes, but appeared to induce them in cells already infected by herpes simplex.

Do I like to lean heavily on phenomena only seen under the lens of a microscope? No.

Do I get nervous when one maverick scientist drives almost all the positive research in a field? Yes.

However, I will allow that we have biological plausibility for the premise of this striking pre-print: vaccinate against shingles and reduce the risk of dementia. Biological plausibility is one thing, though. A convincing study is another!

I do think almost anyone can appreciate the elegance of this study. The authors capitalized on the decision on the part of the Welsh health authorities that, as of September 1, 2013, 79 year olds were eligible to receive the shingles vaccine available at the time (branded in the U.S. as “Zostavax”), but anyone over 80 would never be eligible, a public health technique rarely seen in the U.S., known as “saving money.” Folks 79 years and 51 weeks old had a 47% chance of ultimately getting the vaccine; 80 years and 1 week old, practically zero. By rolling the 53% who opted out together with the 47% who opted in, we are left with a “test” cohort who should be essentially identical in every way to the “control” cohort with the exception of nearly half being vaccinated. (And, yes, for their headline finding, everyone in the eligible cohort was included, not just those who were vaccinated, to avoid the usual confounding which pollutes all observational studies.) By nearly mimicking the conditions of a randomized controlled trial, the authors bravely trumpet that they have shown causality and not mere association: getting the shingles vaccine directly led to a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s!

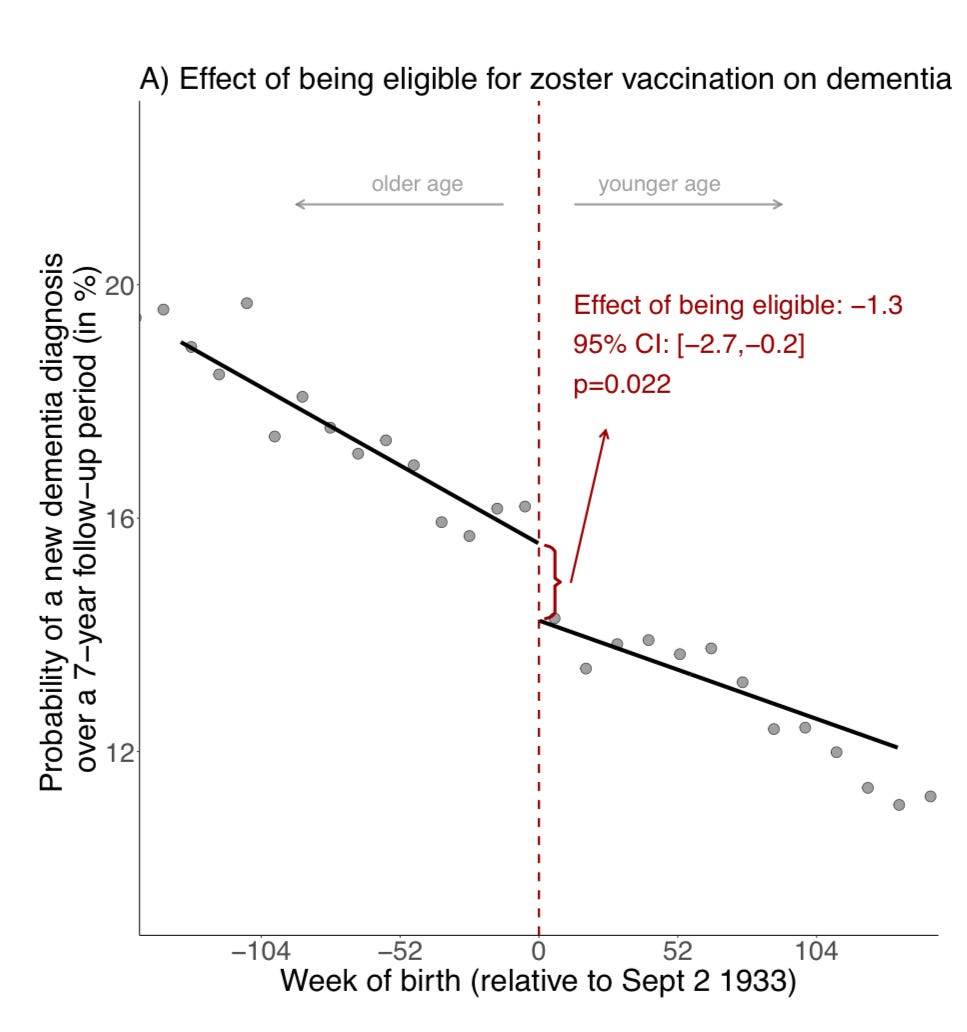

For people who prefer pictures, here is the money shot of their “regression discontinuity” approach:

That step-off right where the eligibility age fell is the “discontinuity.” Now, regression discontinuity designs are not exactly in my wheelhouse, but I can say that they are a fairly — perhaps dangerously — intuitive design, and that the authors did reach statistical significance with their findings.

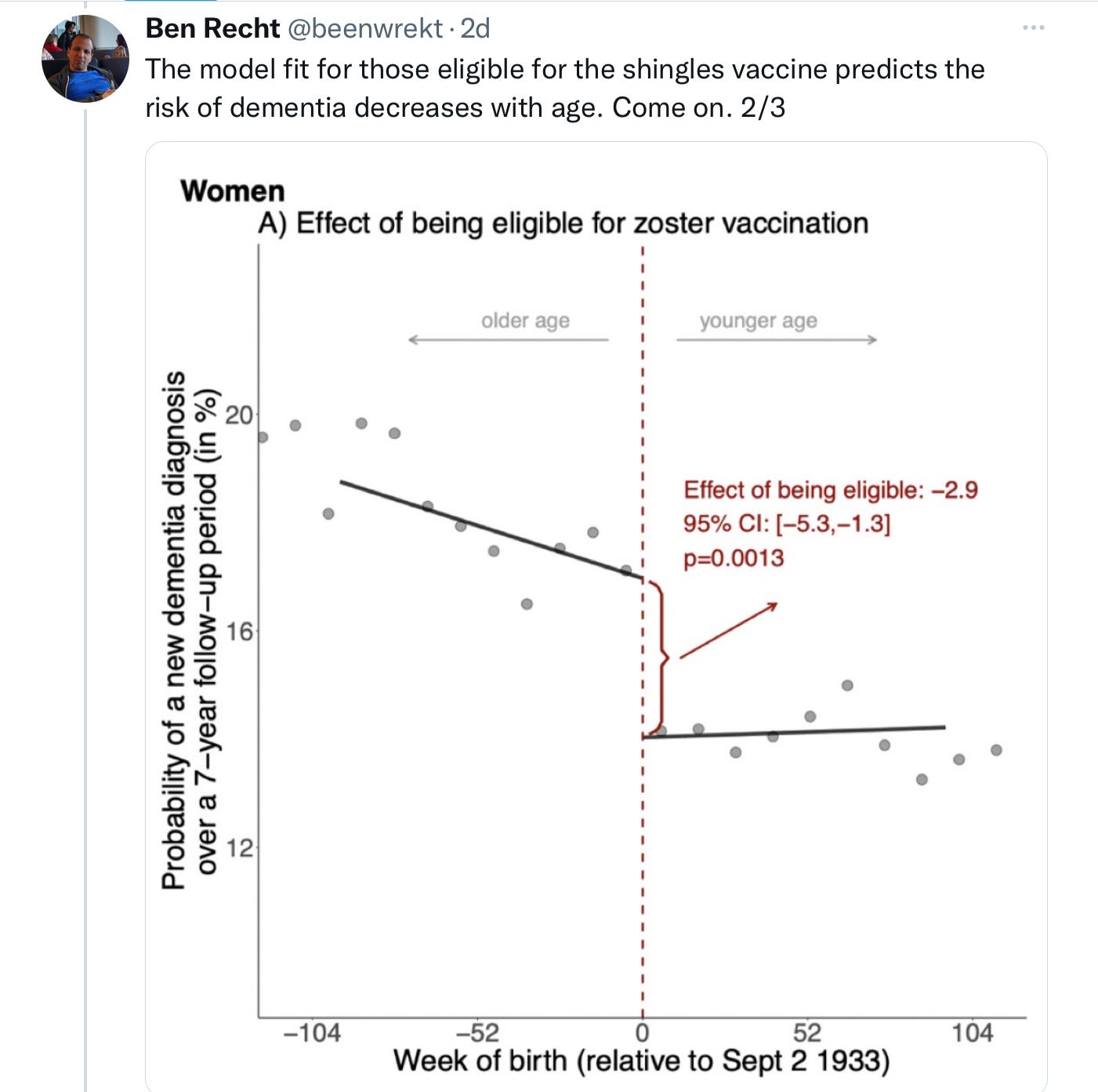

However, a lot of fine studies report findings with statistical significance and still don’t ultimately hold up. Rumblings over this study began promptly on my favorite science platform:

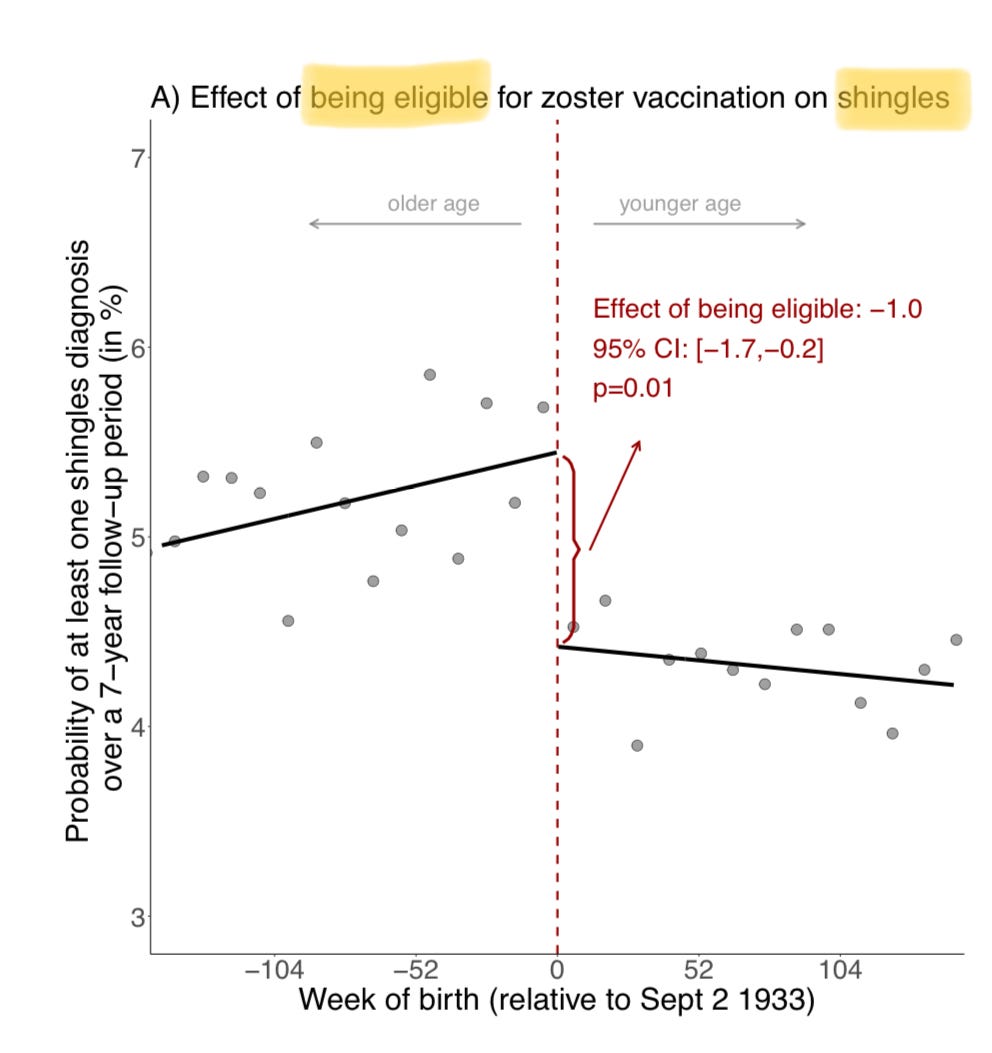

Fair points, both! I, too, had been struck by how modest the effect of the vaccine appeared to be on actual shingles diagnoses, from a little over 5% of the ineligible cohort over 7 years to a little over 4% for the vaccine-eligible cohort:

True, this includes the half of the vaccine-eligible group who opted against shingles vaccination, but still: a 20% reduction in shingles cases is pretty meager, if not shocking — Zostavax was a crappy vaccine, that waned to almost no protection within eight years. This troubles me in terms of the study’s rather striking findings: why would a vaccine so limited at what it’s supposed to do, be so useful at an off-target effect on the same virus it barely inhibits? Also worrisome is what Dr. Prasad noted; the absolute percent reduction on Alzheimer’s diagnosis over those 7 years exceeded the absolute percent reduction in shingles cases. Odd.

Odder still was the difference in effect between men and women. Women had a robust reduction in Alzheimer’s diagnoses if in the vaccine-eligible cohort; men, not so much. Well, actually — not at all. As in, zero. No reduction in dementia.

The authors are aware this is not a good look, and make two attempts to explain it away: 1) they broach the hypothesis that men and women are thought to have different mechanisms by which they develop dementia; and 2) they helpfully note that the confidence interval for men makes it all the way up to a potential 23.9% decrease in dementia, akin to what the women enjoyed, so… maybe this was all just some bad statistical luck?

I am not buying what they are selling. Men received the shot in Wales at the same rate as women; men and women in general are exposed to varicella and develop chicken pox at identical rates (although women are somewhat more inclined to experience shingles); and men and women develop Alzheimer’s at similar age-adjusted incidence rates, as well. Biological plausibility strains to find an explanation for the absolute lack of an effect on men in the vaccine-eligible cohort. Statistical propriety demands that study authors resist the call to claim a “possible” benefit of an intervention based on the outer edge of perfectly balanced confidence intervals.

It’s not clear what really happened in Wales. As study design balloon-popper, Ben Recht, pointed out on Twitter, perhaps nothing at all:

The claimed discontinuity is actually not all that, uh, discontinuous. What’s more, the effect is totally driven by women who were born in the year after September 2, 1933; and there seems to be a relative surfeit of dementia diagnoses in the vaccine eligible cohort born the year after them:

In other words, when the women born one to two years after the Sept 1, 1933 cut-off are studied, they don’t seem to have any benefit from being vaccine-eligible; the slope of their Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis line seems roughly akin to to the cohort that was not vaccine eligible. Of course, if shingles vaccination is really affecting Alzheimer’s risk, one would expect the result to be consistent across time; but looking at the data in more granular fashion suggests that perhaps this was simply a bit of statistical noise for this one sub-cohort of vaccine-eligible women born in the year immediately after the arbitrary cut-off.

Also possible is that this finding for women born between September 2, 1933 and September 1, 1934 is a genuine, statistically-sound result, but not related to shingles vaccination. The epigenetic crew might get excited about the fact that the years leading up to and including 1933 in Wales were rather extreme in terms of hardship; the Great Depression peaked in 1932 with unemployment as high as 70% in Wales. I recall that some of the more compelling ecological data in support of the role of epigenetics — the still-controversial field positing that the patterns of expression of our genes both can be altered by environmental forces as well as subsequently inherited by future generations — derives from the long-term (and multi-generational) health impact of the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s and the Dutch Famine a century later, in which certain diseases (i.e., cardiovascular disease or diabetes) were higher in the children of those who lived through famine than in those born to parents who narrowly escaped famine. I find it highly unlikely that shifts in privation would lead only to changes in rates of dementia; after all, the authors take great pains to show us that only shingles and dementia incidence were affected by vaccine eligibility, and not other major illnesses or causes of death. However, I note this just as a reminder that sometimes “perfect” natural experiments are not as perfect as they might seem.

Overall, the inconsistencies of this study’s results incline me to disregard its findings. The optimist might say, “We have statistically significant data that even a marginally effective shingles vaccine reduces dementia, and now we have a far more effective shingles vaccine (Shingrix) which would surely produce even stronger results.” However, I think the appropriate response is that this study has not convincingly overturned the null hypothesis — that singles vaccination does not affect dementia incidence — and that a randomized controlled trial of Shingrix, presumably in a country with difficulty affording it, is really the next step to evaluate this claim. One would think results would be better with a vaccine which actually works well against the disease it was designed to prevent; unlike Zostavax, Shingrix boasts 90+% efficacy against shingles in the first 4 years, and still north of 80% efficacy at an average of roughly 8 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, Shingrix is already a recommended vaccine for virtually all adults over 50 in the developed world, and it does not require another theoretical indication to merit its adoption.

I do want to be clear that, while I found this one study to be unconvincing, I am open to the idea that viral infections might play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s Dementia. The most compelling research on behalf of this notion is rather counter-intuitive, I admit. Multiple studies in multiple nations have found that treatment with a course of systemic antiviral medications (i.e., acyclovir) significantly lowers the rate of Alzheimer’s Disease. In some places, like Taiwan, the effect was suspiciously large — 90%! In others, like Sweden, it was a more modest 10%. Believers in this hypothesis are fond of citing these studies as evidence that, if antivirals reduce dementia incidence, clearly viruses must cause dementia.

However, from a common sense perspective, one would think that being treated with an antiviral, typically just for a week or so, with no pretense of clearing the persistent viral infection on which we are blaming the neuroinflammation, would have no effect on the likelihood of long-term complications like dementia. Dredging up biological plausibility for a short course of antivirals to halt a chronic process is a challenge. If anything, as a sign of being the 80-90% definitely with a herpes family infection, and a symptomatic one at that, one could expect these would be the people most vulnerable to developing downstream problems like dementia. This, to be sure, is the thesis of our pioneer, Dr. Itzhaki: it’s the symptomatic infections that are most likely to lead to Alzheimer’s.

However, I am not the first to observe that, if we are to enlist all these studies associating a meager week of antivirals with a reduced risk of dementia in support of the “viral dementia” hypothesis, we should probably assume just the opposite! People who present with symptoms of an uncontrolled peripheral flare-up of a herpes virus (whether the shingles of herpes zoster or the cold sores of herpes simplex 1 or genital lesions of herpes simplex 2) must somehow be less likely to have smoldering central nervous system infections causing chronic or periodic inflammation that could lead to Alzheimer’s. If these studies are really describing a true association and not just confounders, it strikes me as far more likely that the diagnosed peripheral herpes infection is the cause of the better dementia outcome, rather than a trivial course of antivirals. I could invent theories as to why this might be the case — most likely, outbreaks in the peripheral nerves could lead to antibody creation that would help keep in check invasion into the central nervous system, or disease activity within that mysterious realm — but this would be little more than spitballing theories.

In any case, I think it’s possible simultaneously to entertain the seemingly contradictory beliefs that persistent neurotropic viral infections might play a role in developing Alzheimer’s Dementia in some people, and that repeated studies suggesting a week’s worth of antivirals reduce dementia risk do nothing to argue that treating people with antivirals will actually reduce dementia. I would recommend against asking your doctor for a valacyclovir prescription for this purpose, especially with antivirals theoretically having a negative effect on the gut biome. However, biological plausibility would allow that a sustained course of daily antivirals might impact dementia risk in case the theory holds true, and indeed a randomized controlled trial testing this idea in patients with early dementia is underway. The VALAD trial should conclude in 2024; while I won’t hold my breath, I’m happy to see this theory tested in a more rigorous manner.

If viral infections penetrating the brain are ultimately deemed to be a major player in the development of Alzheimer’s Dementia, then vaccination against the ubiquitous varicella zoster and herpes simplex viruses should prove useful. We already have the former; I almost never see chickenpox amongst my pediatric patients anymore. Thus, within a few decades we will have another natural experiment to assess: are dementia rates declining among those born late enough to have been given the chickenpox vaccines approved in the U.S. in 1995 and thereby avoiding initial infection with varicella zoster? As to herpes simplex, work on vaccines is underway.

There are good enough reasons to seek vaccination against these pervasive viruses; whether reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s ever becomes one of them, I remain on the fence. Like most complex disease processes, Alzheimer’s Dementia ultimately might be found to be more than one disease, and almost certainly to be caused by many different factors: environmental exposures, poor sleep quality, yet-undiscovered genetic factors, social isolation, and infections, among other possibilities. Alzheimer’s is both terrible and common, a disease worthy of substantial efforts to avoid. Despite this intriguing study out of Wales, however, I am unconvinced that a shingles vaccine will accomplish that goal.

https://doctorbuzz.substack.com/p/will-a-shingles-vaccine-prevent-alzheimers

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.