Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

If you happen to be watching this on a Sunday, Monday, or Thursday and live in the United States, there's a good chance you're watching NFL football tonight. Twenty million people on average tune in to these games, myself included. Go, Eagles! It was my wife who captured why, I think: Football players are simply the best athletes out there in terms of all-around ability — strength, speed, power, and so on.

But of course, something else draws us to these games, something a bit more primal. For lack of a better word, it's the hits: the tackles, the sacks, the bone-crunching collisions. And if we here at Impact Factor had an unlimited licensing budget, you can be sure I'd be showing you some recent highlights right now.

But it's hard to fully enjoy the games if you've done a bit of reading into chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and the effect that these collisions have on the individuals who play professional football.

A recent autopsy study out of Boston University examined the brains of 376 former NFL players; 345 of those brains had evidence of CTE. That's 92%.

Of course, selection bias is at play here; NFL players who donate their brains to science after their death are likely to do so for a reason. But it is getting pretty hard to deny that there is a clear link between NFL play and what amounts to brain damage, at least qualitatively.

The problem with the diagnosis of CTE is that, at least for now, it can only be determined after death. Detecting CTE on autopsy is less than ideal for identifying potential treatment strategies, so I was excited to see a new study leveraging the power of PET-MRI to identify brain injury in NFL players who are still alive.

To introduce you to this study, appearing in JAMA Network Open, I first need to introduce you to an 18-kilodalton protein called translocator protein (TSPO). TSPO used to be known as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor as it was found to bind diazepam. But that does not seem to be central to its purpose.

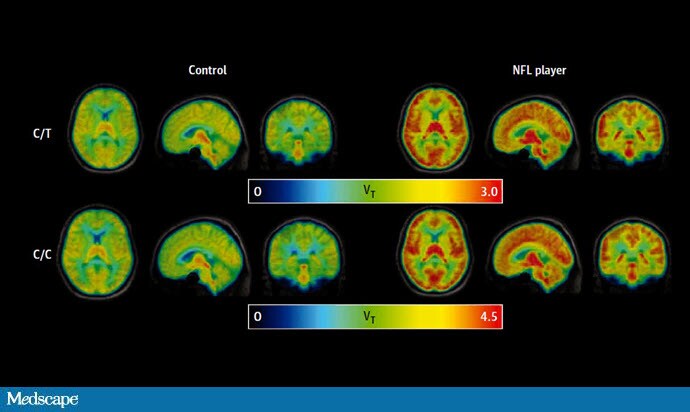

Rather, it lives on the surface of mitochondria and seems to be a very sensitive marker of inflammation and repair. When tissue is damaged, TSPO is upregulated, and you can see that upregulation in a PET scan using a selective tracer chemical.

With that background, we can understand the JAMA Network Open study. Researchers, led by Jennifer Coughlin at Johns Hopkins, enrolled 27 individuals, all of whom had played in the NFL in at least the past 12 years. The average duration of play had been about 6 years. There were 14 linemen, nine linebackers, two wide receivers, and two kickers.

To serve as controls, they included 27 elite swimmers — a noncontact sport unless you're doing it wrong — all of whom had at least been in NCAA Division III or higher programs. After subjecting both groups to a battery of neuropsychiatric tests, they underwent PET-MRI scans. And the findings are pretty stark.

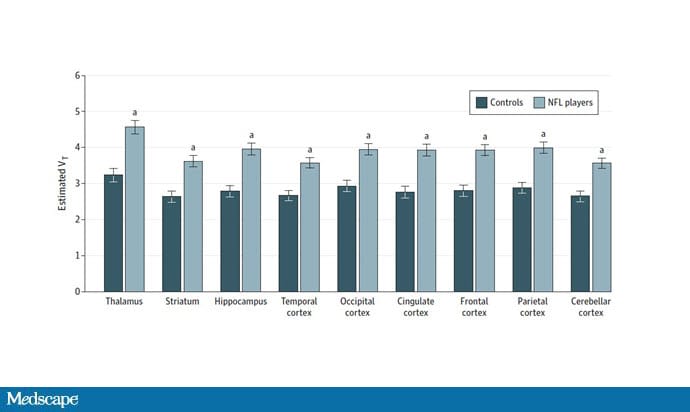

Across the board, you see higher TSPO levels in the former NFL players. Again, this is indicative of injury, repair, or both. This was a global phenomenon, basically in every region of the brain examined.

Quantitating the levels of TSPO anatomically, you can see significantly more damage and/or repair in the frontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and hippocampus, which is consistent with autopsy CTE results.

The NFL players performed similarly to the swimmers on cognitive tests, with the notable exception of tests of learning and memory. The NFL players also had much more variability in their scores than the swimmers, suggesting, not surprisingly, that NFL play likely affects different players differently. I was hoping to see some comparison of the kickers to the rest of the team, but we were not provided with that data.

The authors note that the performance on the cognitive tests was not correlated with the degree of TSPO activation in the NFL players. So yes, overall, NFL players had more TSPO, and yes, overall, NFL players had worse memory scores, but it wasn't the same NFL players who had both issues. So this new scan is not a slam dunk for all that ails NFL players' brains.

In a macabre way, we may not really know the value of these scans until much later, when it becomes clear that these players are or (hopefully) are not suffering from dementia, and, even later, on autopsy.

But I am hopeful that, if not this particular diagnostic test, we will make progress on some diagnostic test to identify the harbingers of CTE in the living. Without that, treatment is just a pipe dream.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.