When a patient cannot say how much pain they are in, such as when they are sedated, have dementia, or are nonverbal, clinicians turn to facial expressions to guide treatment.

Tension, frowning, or grimacing may indicate pain, and bedside assessment scales consider those elements.

Clinicians typically must be with patients to complete those measures, however, which is not always possible in a busy hospital or nursing home, and this can lead to delays in administering care.

That's one reason researchers are training artificial intelligence (AI) models to take up the task.

Researchers have developed an AI algorithm that can interpret images of patients' faces to detect when they are in pain, paving the way for around-the-clock monitoring.

One group described their pain-recognition software at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

The developers provided the AI system with examples of patients experiencing pain. Using computer vision and deep learning, the algorithm learned to recognize when other patients were in pain.

The investigators compared their AI system's results to those derived from the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT), which clinicians use to estimate pain on the basis of patients' facial expression, muscle tension, body movements, and intubation status. Relative to CPOT, the AI's readings were 88% accurate.

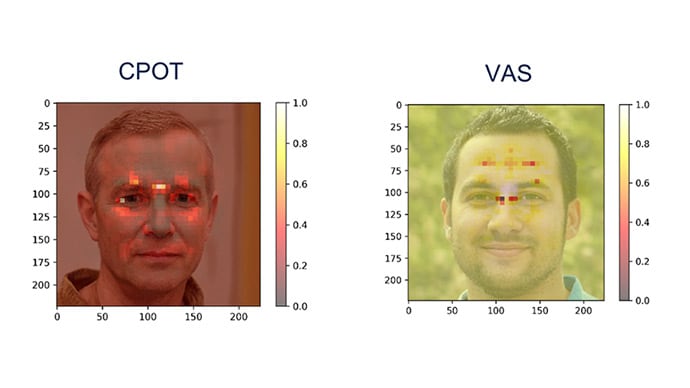

To better understand how AI detects pain, researchers generated heatmaps to identify which areas of the face were most important for the AI’s analysis. They systematically obscured parts of the face and saw how each omission influenced the model's response. Their analysis revealed that AI zeroed in on areas around the eyebrows, lips, and nose. The heatmaps are superimposed over AI-generated faces, not actual patients.

AI was less accurate (66%) in comparison with patient-reported measures. Patient-reported measures encompass "more emotional and psychological components than CPOT," which could explain the difference, reported lead study author Timothy Heintz, a fourth-year medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Heintz conducted the research with Arthur Wallace, MD, PhD, and other colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco.

Wallace is the CEO and founder of Atapir, a company that is developing a noncontact monitor for patients in hospitals and nursing homes. The monitor could be used to measure pain, as well as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood oxygen saturation, perfusion, and mood, according to the company's website.

Use in Nursing Homes?

Other pain recognition tools are already commercially available in some countries.

An Australian company, PainChek, recently announced plans to study its pain assessment tool in nursing homes in the United States in an effort to obtain regulatory clearance. The tool has been studied in infants and in adults and already has received clearance in the European Union, the UK, Canada, and several other countries.

The PainChek phone application gauges pain by automatically assessing facial expressions. It also considers information that users enter about patients' movements and vocalizations.

For the US study, investigators plan to enroll 100 patients with moderate to severe dementia who are unable to self-report their pain. The researchers will compare PainChek's pain rating with that of the Abbey Pain Scale.

Beware Oversimplification and Underestimation?

While automated pain-recognition technology holds promise, doctors should not overrely on it, experts have said.

Kenneth M. Prkachin, PhD, with the University of Northern British Columbia, Canada, and Zakia Hammal, PhD, with the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, in an article published in 2021 in Frontiers in Pain Research cautioned clinicians not to discount the possibility that a patient is in pain on the basis of an "oversimplified interpretation of the meaning of a pain score derived from automated analysis of the face."

Many patients who are in pain do not show it, and studies have found that clinicians tend to underestimate pain, they wrote.

Researchers working on this technology should examine a range of variables and patient populations, they added.

"To date, no attention has been applied to how automatic pain detection may vary between men and women, people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds, or context, to name just a few factors," Prkachin and Hammal wrote.

Although studies have explored the use of high-tech methods to distinguish genuine pain from "faked pain," such applications may be imperfect and "open to abuse," they said.

AI's greatest potential in this area may lie in facilitating early pain research, they suggested: "A form of assessment that can automatically yield reliable, valid and continuous information about how and when people (and animals) are expressing pain holds promise to enable detailed studies of pain modulation that are prohibitively difficult to perform with human observers."

Errors and Privacy Concerns

Antonio Forte, MD, PhD, with the Division of Plastic Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, and his colleagues outlined other potential pitfalls of this type of technology in an article published this year in the journal Bioengineering.

"Relying only on inaccurate models could lead to dangerous or inappropriate decisions, such as misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, or even legal actions," Forte and his co-authors wrote. "For instance, misdiagnosing certain conditions based on inaccurate pain detection models may lead to low-quality or no care, or prompt unnecessary surgery or medication."

Privacy and autonomy are other concerns. Some patients might refuse to allow their face to be analyzed, they noted.

The study shows that AI has the potential to be "similarly reliable" in performing pain assessments without taking as much time and could better standardize the capture of patients' experiences with pain, David Dickerson, MD, chair of the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Pain Medicine, told Medscape Medical News.

Currently, a busy clinician who administers pain medication has "to come back to that patient to reassess them to see how the medicine works," he said. Meanwhile, other patients, colleagues, and the electronic health record are vying for their attention.

A Major Pivot

Quantifying pain in a standardized way is a challenge, and clinicians have come to understand pain as a subjective experience.

"My 7 out of 10 is going to be different than a 7 out of 10 from the patient down the hall based on their lived experience, their nervous system, and even their understanding of what the numbers mean and how they were explained to them," Dickerson said.

Best practice calls for regular assessment of patients' pain and a reassessment after patients have received treatment.

New research into automated pain detection by AI raises the possibility that facial expression could be used as a biomarker for pain, which would be "a major pivot," Dickerson said.

"If pain is a subjective experience, now we're looking for objective findings," he said.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting: Abstract 4 (LBA04). Presented October 14, 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.