The U.S. government spends over $160 billion annually on scientific research. This massive expense is marketed to taxpayers as an investment in groundbreaking research that fuels innovation and discovery. In truth, much of the federal science budget is expended on questionable and even fraudulent research. It’s time we eliminate it.

The academy has been in an uproar since Donald Trump began his second term as president in January. One article after another in seemingly every major science media outlet has lamented the administration’s dramatic cuts to federal science funding, all making essentially the same argument: the administration’s policies “imperil the nation’s health, economy and national security,” as Scientific American put it.

This response is understandable, but it fails to grapple with the rampant fraud, ideological bias and proliferation of low-quality research driving the administration’s cuts to science funding. Much of the academic work taxpayers are forced to fund provides no benefit or, even worse, causes serious harm in a variety of ways. As a result, the cuts to federal science funding need to continue until science is an entirely private enterprise.

Publicly funded fraud

This is an admittedly radical proposal, but it’s an appropriate response to the systemic failure we need to correct. Taxpayers spend a king’s ransom on science each year yet the return on our investment is underwhelming.

In September 2024 for example, Science reported that a veteran neuropathologist running the National Institute on Aging's Division of Neuroscience–with an annual budget of $2.6 billion–had probably falsified images in key studies used to justify developing novel drugs for Parkinson’s Disease—an effort that carries an additional price tag of hundreds of millions of dollars. “I’m floored,” Mount Sinai neurologist Samuel Gandy told Science during an interview. “Hundreds of images. There had to have been ongoing manipulation for years.”

Other high-profile fraud cases underscore the problem: take Anil Potti, a Duke University researcher who faked cancer trial data, misleading patients and squandering millions in grants, or the infamous case of Woo-Suk Hwang, whose fabricated stem cell research misled global science for years. And the problem persists. Harvard’s prestigious Dana-Farber Cancer Institute was forced to retract seven studies just last year following the discovery of manipulated images in the research.

A few bad apples?

Academics who rely on federal grant funding will insist that these fraud cases represent a few bad apples, unfortunate outliers that besmirch the reputations of researchers who do good work. This analysis misses the mark, however. “Fake studies have flooded the publishers of top scientific journals,” The Wall Street Journal reported last May, “leading to thousands of retractions and millions of dollars in lost revenue.”

The problem is so massive that one Northwestern University researcher called it “an existential crisis” for science in February 2024. Studies estimate that roughly 50% of published research in fields like psychology and biomedicine fails to replicate. A 2015 analysis in PLoS Biology found that irreproducible preclinical research, "with government sources providing the majority of funding," costs $28 billion annually in the U.S. alone. These aren’t outliers but symptoms of a dysfunctional system.

Tactical science

This leads to a related but equally troubling concern: federal funding is often used to advance political causes with zero scientific merit. Examples run the gamut of academic disciplines. From climate change and infectious disease research to pediatrics, there is ample evidence of scientists incorporating ideological dogma into their conclusions. It’s what science policy expert Roger Pielke, Jr. calls tactical science: research “designed and constructed to serve extra-scientific ends, typically efforts to shape public opinion, influence politics, or serve legal action.” Here’s one particularly egregious example:

Ironically, much of this tactical science is used by activists like our new Health and Human Services secretary RFK, Jr. to justify his radical proposals, including chemical regulations the science community opposes. For example, many scientists mocked Kennedy for claiming during his senate confirmation hearing that fluoride is a neurotoxin; few of them stressed that he cited an NIH-funded study from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), one of the most prestigious peer-reviewed publications in the world.

It’s the same story with other popular health scares. The ongoing activist campaign against low-risk pesticides? Built on a foundation of sloppy epidemiology heavily funded by the federal government. In one truly galling example, the EPA went to court a few years ago to challenge an insecticide ban that was proposed after EPA-funded research wrongly linked the chemical to health harms in children.

The examples go on and on: “ultra-processed” food linked to early death; food dyes associated with ADHD in children; PFAS harms infants; BPA causes endocrine disruption; tampons expose women to lead; sugar is addictive. If you’re a taxpayer, you paid for all these studies, and they benefit no one except trial lawyers and activist groups who raise money by pushing chemical scares.

Non-existent benefits of public science funding

The opposition to president Trump’s funding cuts revolves around the claim that government support for science yields clear benefits. But history doesn’t bear out this claim. Biochemist Terrence Kealey, author of the seminal text on this subject, has highlighted a striking piece of evidence at the country level.

The industrial revolution began in Britain; and the US experienced a similar explosion in industrialization not long after, yet neither country made significant public investment in science during this period, Kealey has pointed out. Meanwhile, the governments of France and Germany poured enormous resources into scientific research yet lagged far behind the Americans and the British in economic development.

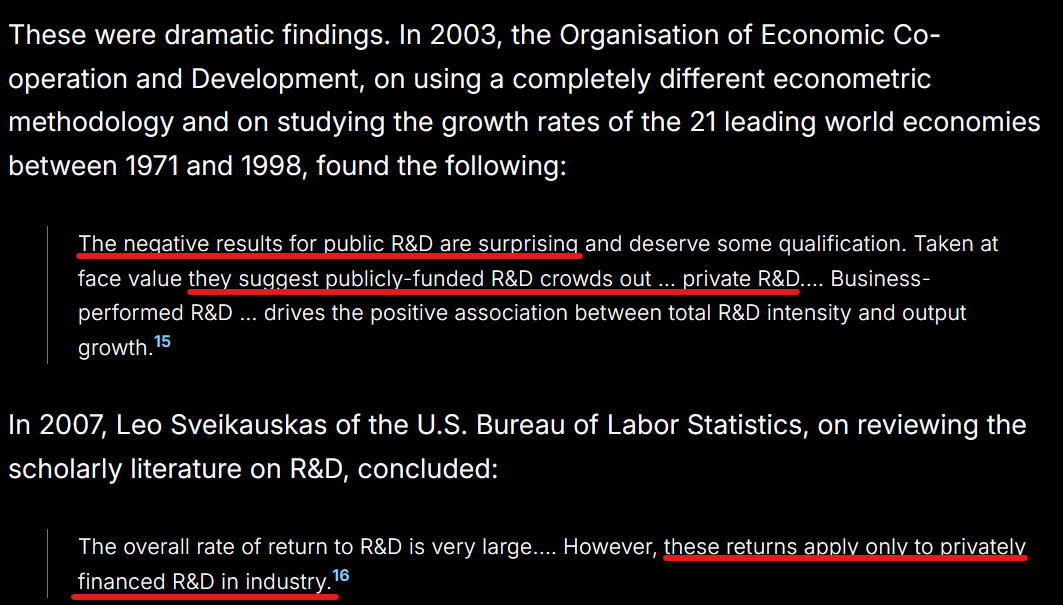

This natural experiment is hard to explain on the view that public support for science is essential. So is the spade of government-sponsored audits examining the supposed economic benefits of public research funding, which “have emerged as the most effective discreditors of the idea,” Kealey argued in a 2021 policy brief for the Cato Institute. Here are the conclusions from just two of those audits:

Importantly, the campaign to ramp up public R&D investment in the US wasn’t driven by a dearth of scientific progress–there was plenty of that at the time–but politics, specifically the fear that America was losing the Cold War. Of course, the Soviet Union was an economic basket case characterized by famine and other horrid deprivations. The US was never at risk of losing the Cold war—meaning the push for expanding public science funding was premised on a falsehood from the beginning.

What about public goods?

Perhaps the most common objection to this privatization proposal is the assumption that private institutions, corporations and foundations primarily, won’t fund a lot of research because it lacks immediate commercial payoff, and thus governments must step in and support this “public good.” The argument is some 400 years old, but it’s never been compelling.

Before World War II, private entities drove foundational science. In fact, “private funding was the main and often only support for scientific endeavors” before the 1940s, Nature explained in 2016. Importantly, that observation provided context for the article’s broader thesis:

“... [T]he stagnation in federal funding since 2003 has led to increasing concerns that science will suffer, because more risky or preliminary projects are not likely to get funded … Money from private foundations can fill this financial gap to a degree” [my emphasis].

High-profile examples of this phenomenon from the past aren't hard to find. The Rockefeller Foundation pioneered infectious disease prevention and treatment in the early 20th century without a dime of public money. “Between 1913 and 1950, the RF invested $100 million in health programs,” University of Geneva historian Ludovic Tournès noted in 2022:

“At first, the Rockefeller Foundation focused on public health issues, especially in Latin America, where in 1916 it conducted surveys in many countries, followed by programs to eradicate diseases such as hookworm, malaria and yellow fever.”

The foundation’s “main characteristic is that it sprang from, and owes its considerable financial resources to, American capitalism,” Tournès added. This private model delivered results more efficiently than many modern publicly funded programs, supporting the case for privatization.

The simple fact is that private R&D spending dwarfs public investment, with as much as 70 percent of science financed by corporations and charities. In the US, the difference is similarly massive. Of the $892 billion total invested in R&D in 2023, “the business sector funded $673 billion and the federal government funded $164 billion,” the National Science Foundation reported in February.

Creative destruction

Economists often talk about creative destruction, a process by which innovation drives economic growth by creating new industries, products, or methods that displace their obsolete predecessors. The scientific establishment needs to undergo something similar to creative destruction.

Like the rest of us, academics can convince people to voluntarily pay for their services. Worthwhile research, like innovative crop breeding research or vaccine development, will find private support, as it always has. Academics who study “Decolonial Eco-Queer Theories” will probably have to find new jobs.

Cameron English is a writer, editor and co-host of the Science Facts and Fallacies Podcast. Before joining ACSH, he was managing editor at the Genetic Literacy Project.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.