In California, a proposed “wealth tax” targeting the concept of founder-controlled companies threatens to fracture the tech ecosystem.

The measure, if passed, would charge the state’s billionaires 5% of their net worth, which includes assets they’ve already paid taxes on, supposedly just once. Unsurprisingly, billionaires aren’t super enthusiastic, but it’s not just because of higher taxes. Under the proposal, a person’s ownership stake in a private company is “presumed” to be no less than their share of voting or control rights.¹ Since founders of startups commonly control more than they directly own (via agreements like super-voting shares), this tiny “one-time” tax starts to take on a whole new meaning.

The proposal needs 874,641 signatures to wind up on the November 2026 ballot. But whether it actually goes through matters less than what it’s already signaled to the tech industry: California’s political scene is chaotic at best, and downright hostile at worst. Last week, Pirate Wires broke the news that 20 billionaires are already planning to leave the state. For all of Gavin Newsom’s protest, California seems to have nailed the self-deportation effort better than anyone else.

It may seem kind of insane that a small group of people (in this case, a powerful union and a few academics) can effectively add what some are calling an unprecedented asset seizure to the ticket come November. But, in California, where “direct democracy” reigns supreme, this is just the latest flavor of dysfunction.

For more than 100 years, the state’s ballot prop system has been billed as a cure for ineffective government and regulatory capture. If voters can directly vote on a new law, you don’t have to wait for the legislature to act. A straight shot to fair and effective policy… right?

In practice, the system has produced a chaotic marketplace in which only the well-funded can participate, voters are manipulated into decisions they don’t fully understand, and bad policy gets locked in for generations.

A brief history.

How We Got Here

In 1911, Governor Hiram Johnson wanted to break Big Railroad’s chokehold on Sacramento.

After his sweeping win, Johnson’s Progressive Republican coalition proposed a suite of constitutional amendments. Among those, Proposition 7 passed with an overwhelming 76% of Californians voting in favor.

Prop 7 was a massive change, allowing citizens, by simple popular vote, to veto laws already passed by the legislature, recall elected officials, write new laws, and, incredibly, create constitutional amendments.

The system had remarkably few guardrails. In most states, constitutional amendments require supermajorities or legislative approval. In California, they can be enacted, via ballot prop, by a simple majority of voters. And, once an initiative passes, the legislature generally cannot amend or repeal it without going back to voters — unless the initiative itself explicitly allows changes. This kills any shot of lawmakers turning insane propositions into workable policy.\

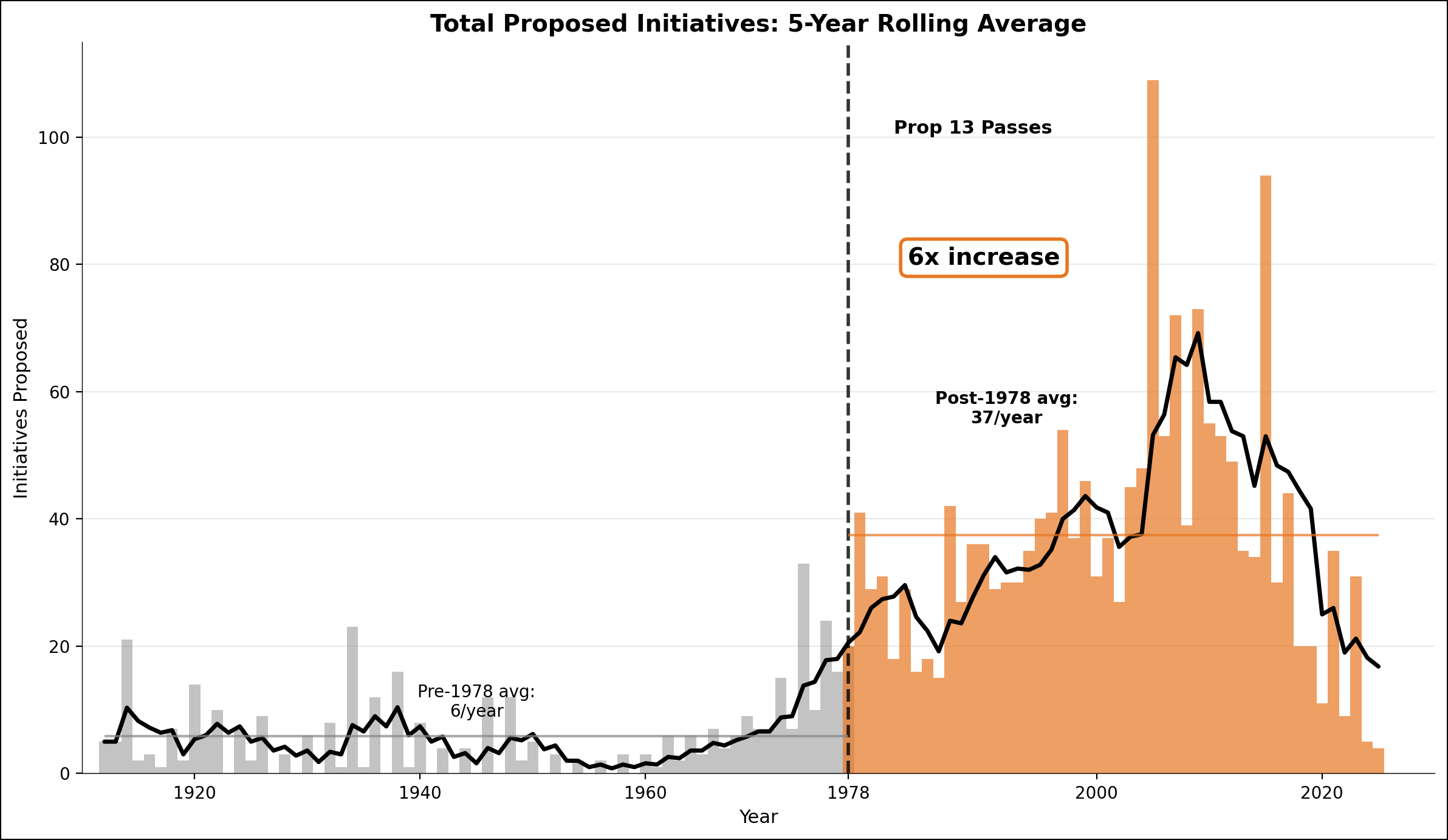

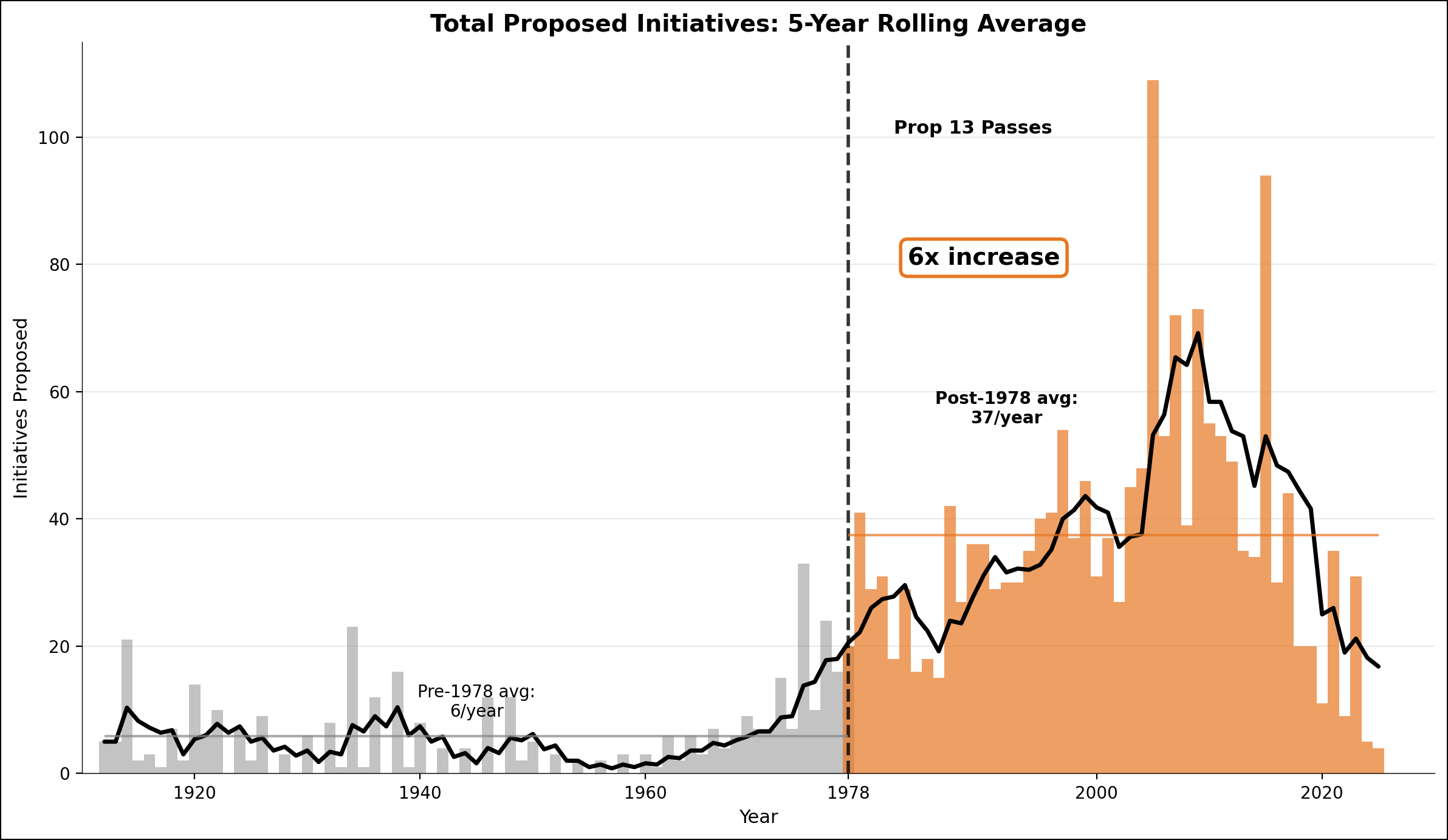

At first, the system worked okay. There were some decent ballot measures — granting women the right to vote, giving the state more authority to regulate railroads, etc. — but they were used sparingly. From 1911 to 1978, the state approved a few ballot propositions per year.

Until Prop 13.

California Starts Ballotpropmaxxing

In 1978, Californians voted on a ballot prop that created a constitutional amendment capping property tax rates at 1% of the assessed value, an unmet promise Republicans had run on for years. The measure passed overwhelmingly because, like all successful ballot props, it sounded nice, especially for those who already owned homes (in 1978, that was most Californians). As long as they didn’t sell the property — which would trigger an update on the taxable value — Prop 13 kept the annual assessment to a 2% increase, creating a lock-in effect. Better to stay put and pay less tax than to move and pay more. This, among other variables, limited the availability of homes for new families, making Prop 13, much like Social Security, another genius piece of Boomer Technology™, safeguarding their wealth from younger generations.

After Prop 13 passed, the signature-gathering industrial complex was born.

Californians realized that using the ballot prop process to create policy was a lot easier than getting legislators to do something. In areas like taxes, where lawmakers were bound by the realities of making sure the government keeps the lights on, the ballot prop process could put politically or functionally impossible proposals on the ballot. This was naturally attractive to activists, corporate interests, and ideologues — as long as they had the means to pay.

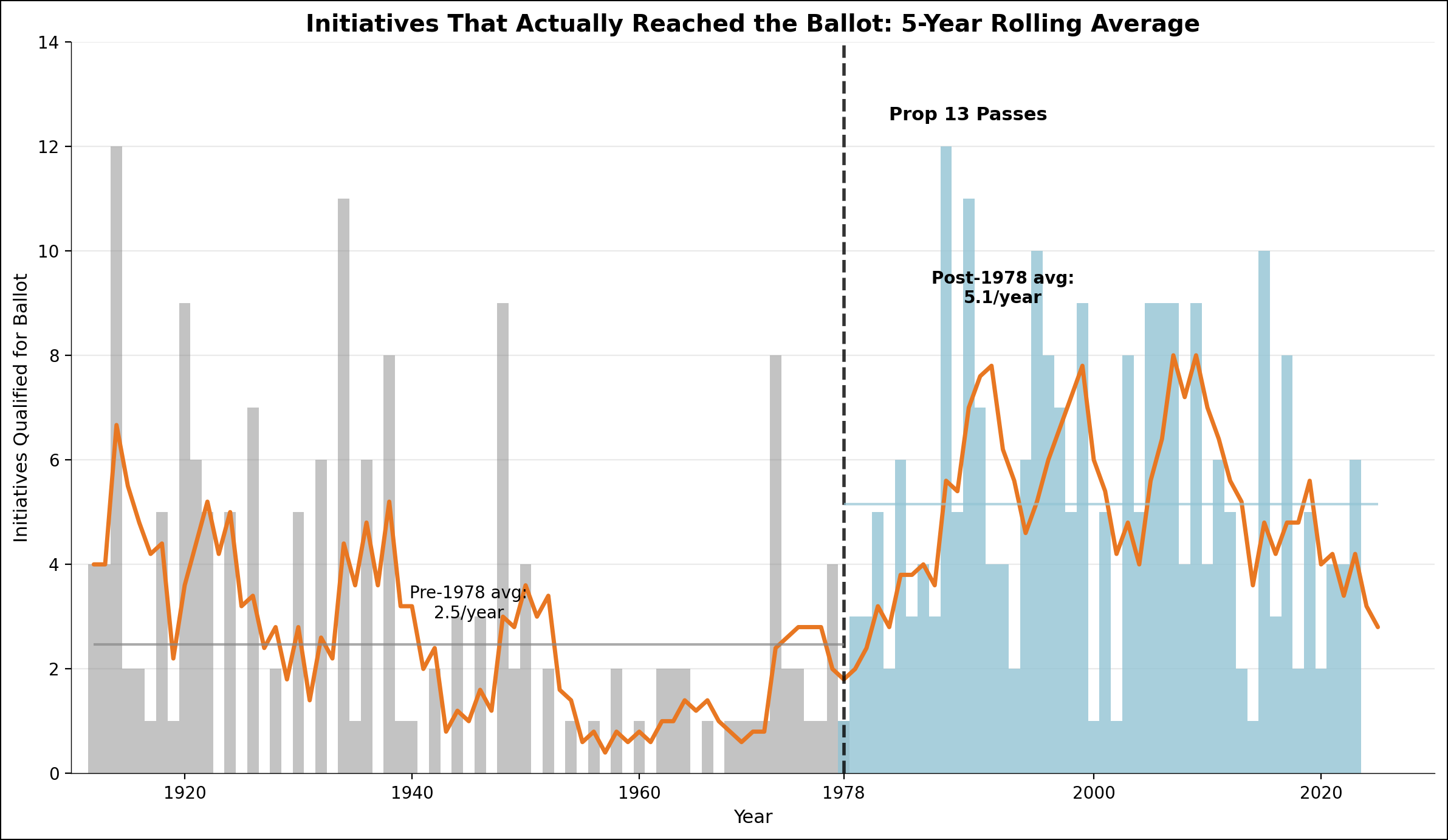

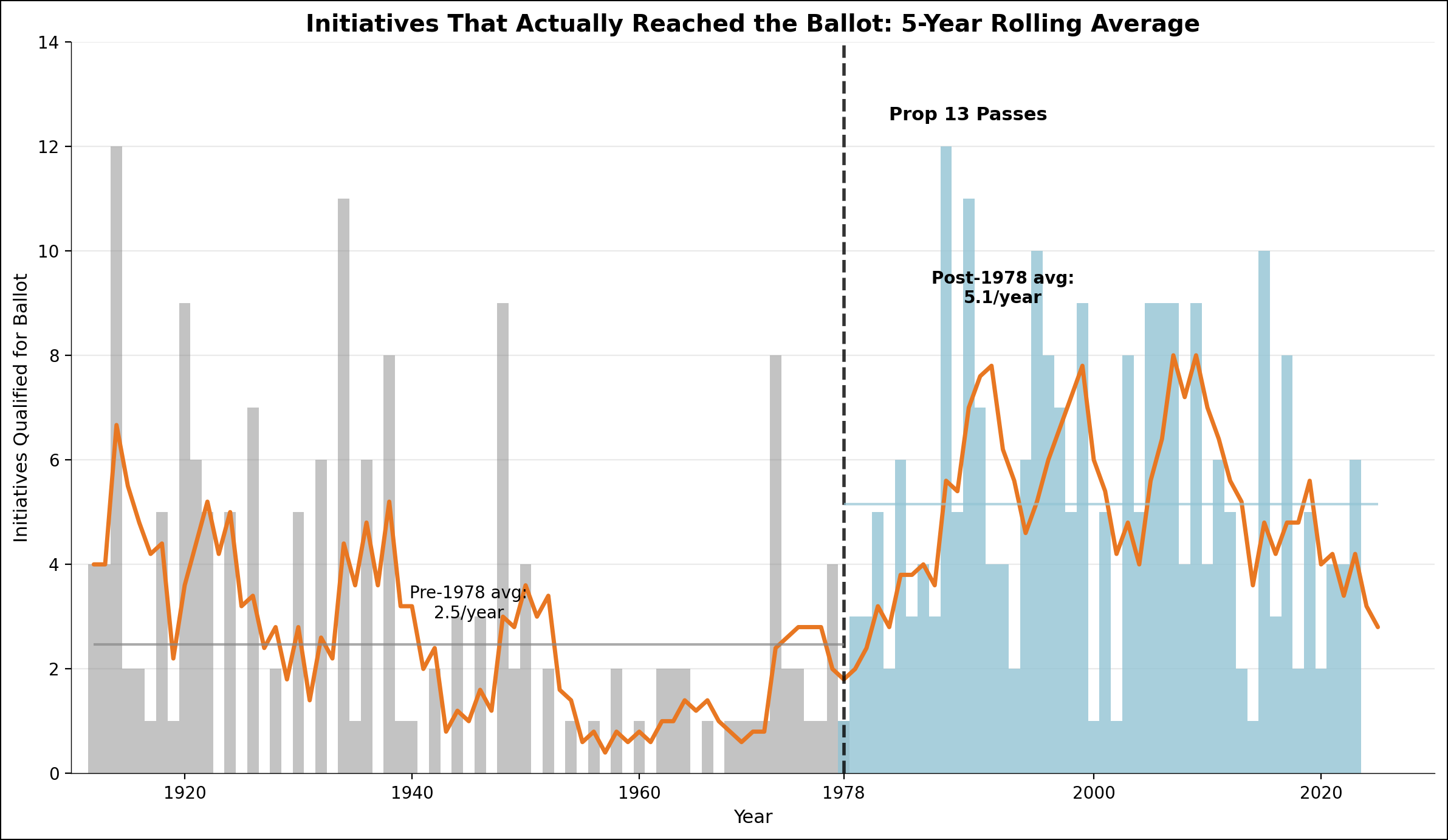

For the average person, the barrier to putting an initiative on the ballot (typically upwards of half a million signatures) is high. But motivated groups with enough resources can pay a few million to hire signature gatherers. And once you’re on the ballot, the odds of passage are decent; throughout state history, 34% of qualified initiatives have become law.

To illustrate the power of “direct democracy” aka motivated groups getting themselves things, I offer Prop 30 and Prop 55.

In 2012, following the Great Recession, California voters passed Prop 30, which enacted “temporary” tax increases on sales and income for high earners. This nice-sounding plan to ensure schools stayed open and teachers got paid seemingly worked: California went from a $16 billion deficit in 2012 to a $2.7 billion surplus in 2016. But as the expiration date for those “temporary” taxes drew near, the hospitals, schools, and unions that initially backed the measure warned once again of terrifying budget shortfalls, and came up with a solution: Prop 55. Proponents — trade organizations and unions for teachers and hospitals (never to be left out, Medi-Cal stood to get a chunk of the new revenue) — spent almost $60 million on ads, and it passed decisively in 2016, extending the tax on high earners until 2030 and arguably contributing to an insanely wasteful environment where superintendents attend the Grand Californian Hotel and Spa at Disneyland on taxpayers’ dime. Now, amazingly, a new initiative titled “The California Children’s Education and Health Care Protection Act of 2026” could potentially make the hike permanent, once and for all.

The ballot proposition process is dominated by labor unions, corporations, and single-issue advocacy groups that know which words to use to tug at voters’ heartstrings, but remember: they’re gunning for what’s best for them, too. The same union behind the billionaire wealth tax — Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West — has spent around $37 million to get dialysis clinic-regulations onto the ballot three separate times. Voters keep turning them down, but it doesn’t matter, because the constant threat of these initiatives serve as leverage when the union makes demands of the clinic companies.

Direct democracy: where bad ideas don’t die. They just get more expensive.

Wherein California Accidentally Votes for Organized Shoplifting Rings

Remember earlier, when I said — so brazenly, you might’ve thought — that special interest groups used ballot props to downright manipulate voters?

Prop 47, titled “The Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act,” passed in 2014 with 60% of the vote. The pitch was carefully crafted: increase funding for mental health programs (to clean up neighborhoods), and schools (to ensure students got the attention they needed). With a snappy, benevolent-sounding title like that, why wouldn’t you vote yes? Well, per the fine print: to raise this money, California would reclassify simple drug possession and theft under $950 from felonies to misdemeanors. Most didn’t realize the risk: by making theft under $950 a misdemeanor, in practice Prop 47 stopped police from booking shoplifters at all. Even if they caught them red-handed, all they usually got was a slap on the wrist. Enforcement collapsed and shoplifting rates exploded. The hundredth offense was just the same as the first. Why stop?

In fact, Prop 47 is directly responsible for the proliferation of organized shoplifting rings. Teams would carefully ensure they stole $949 of goods at a time and get away scot free. Stores responded the only way they could: locked shelves, plexiglass barriers, and employees tailing every customer. If you’ve ever wondered why you had to ring a doorbell to get shampoo in San Francisco, this is why.

From its inception, law enforcement argued Prop 47 would make their lives hell. California’s legislature would never have passed it. But thanks to the magic of direct advertisement and the AG’s choice to name it “The Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act” instead of the “Unlimited Shoplifting Act,” voters overwhelmingly approved the measure and soon came to regret it. (Eventually, in a rare feat for California, voters realized their mistake and reversed many of its changes. Prop 36, which passed in 2024 with 68% approval, restored felony penalties for repeat theft and drug offenses.)

No Exit

Much of California’s deathspiralling can be traced back to ballot props. Taxes too high? Take it up with the hospital lobby! Want to buy a house? Unfortunately you’ve got Boomer NIMBYs that will never sell and would rather burn alive than let you reduce their property values! Want to go to a convenience store? Have fun getting stalked by the employees who have to unlock your $8 deodorant!

This is the endgame of California’s ballot prop system: even when everyone agrees a law isn’t working, fixing it requires another statewide campaign. If it takes a decade to end organized shoplifting rings, how confident are you that voters will change less visible (but equally destructive) policies? We’re still waiting for Prop 13’s property tax lock-ins to end despite generations of Californians complaining about home prices.

We like to gripe that the politicians don’t do anything. But circumventing the standard, sluggish legislative process outsources the messy business of governance to faceless unions and NGOs. And the voters? When they see an initiative on the ballot, they don’t read past the title. They watch a couple of ads. They see a billboard saying “No to Corporate Greed.” They say hello to the nice man or woman asking for their signature on the sidewalk. And then they vote. This is what California chose for itself.

In 1911.

— Ryan Hassan

Until Prop 13.

California Starts Ballotpropmaxxing

In 1978, Californians voted on a ballot prop that created a constitutional amendment capping property tax rates at 1% of the assessed value, an unmet promise Republicans had run on for years. The measure passed overwhelmingly because, like all successful ballot props, it sounded nice, especially for those who already owned homes (in 1978, that was most Californians). As long as they didn’t sell the property — which would trigger an update on the taxable value — Prop 13 kept the annual assessment to a 2% increase, creating a lock-in effect. Better to stay put and pay less tax than to move and pay more. This, among other variables, limited the availability of homes for new families, making Prop 13, much like Social Security, another genius piece of Boomer Technology™, safeguarding their wealth from younger generations.

After Prop 13 passed, the signature-gathering industrial complex was born.

Californians realized that using the ballot prop process to create policy was a lot easier than getting legislators to do something. In areas like taxes, where lawmakers were bound by the realities of making sure the government keeps the lights on, the ballot prop process could put politically or functionally impossible proposals on the ballot. This was naturally attractive to activists, corporate interests, and ideologues — as long as they had the means to pay.

For the average person, the barrier to putting an initiative on the ballot (typically upwards of half a million signatures) is high. But motivated groups with enough resources can pay a few million to hire signature gatherers. And once you’re on the ballot, the odds of passage are decent; throughout state history, 34% of qualified initiatives have become law.

To illustrate the power of “direct democracy” aka motivated groups getting themselves things, I offer Prop 30 and Prop 55.

In 2012, following the Great Recession, California voters passed Prop 30, which enacted “temporary” tax increases on sales and income for high earners. This nice-sounding plan to ensure schools stayed open and teachers got paid seemingly worked: California went from a $16 billion deficit in 2012 to a $2.7 billion surplus in 2016. But as the expiration date for those “temporary” taxes drew near, the hospitals, schools, and unions that initially backed the measure warned once again of terrifying budget shortfalls, and came up with a solution: Prop 55. Proponents — trade organizations and unions for teachers and hospitals (never to be left out, Medi-Cal stood to get a chunk of the new revenue) — spent almost $60 million on ads, and it passed decisively in 2016, extending the tax on high earners until 2030 and arguably contributing to an insanely wasteful environment where superintendents attend the Grand Californian Hotel and Spa at Disneyland on taxpayers’ dime. Now, amazingly, a new initiative titled “The California Children’s Education and Health Care Protection Act of 2026” could potentially make the hike permanent, once and for all.

The ballot proposition process is dominated by labor unions, corporations, and single-issue advocacy groups that know which words to use to tug at voters’ heartstrings, but remember: they’re gunning for what’s best for them, too. The same union behind the billionaire wealth tax — Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West — has spent around $37 million to get dialysis clinic-regulations onto the ballot three separate times. Voters keep turning them down, but it doesn’t matter, because the constant threat of these initiatives serve as leverage when the union makes demands of the clinic companies.

Direct democracy: where bad ideas don’t die. They just get more expensive.

Wherein California Accidentally Votes for Organized Shoplifting Rings

Remember earlier, when I said — so brazenly, you might’ve thought — that special interest groups used ballot props to downright manipulate voters?

Prop 47, titled “The Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act,” passed in 2014 with 60% of the vote. The pitch was carefully crafted: increase funding for mental health programs (to clean up neighborhoods), and schools (to ensure students got the attention they needed). With a snappy, benevolent-sounding title like that, why wouldn’t you vote yes? Well, per the fine print: to raise this money, California would reclassify simple drug possession and theft under $950 from felonies to misdemeanors. Most didn’t realize the risk: by making theft under $950 a misdemeanor, in practice Prop 47 stopped police from booking shoplifters at all. Even if they caught them red-handed, all they usually got was a slap on the wrist. Enforcement collapsed and shoplifting rates exploded. The hundredth offense was just the same as the first. Why stop?

In fact, Prop 47 is directly responsible for the proliferation of organized shoplifting rings. Teams would carefully ensure they stole $949 of goods at a time and get away scot free. Stores responded the only way they could: locked shelves, plexiglass barriers, and employees tailing every customer. If you’ve ever wondered why you had to ring a doorbell to get shampoo in San Francisco, this is why.

From its inception, law enforcement argued Prop 47 would make their lives hell. California’s legislature would never have passed it. But thanks to the magic of direct advertisement and the AG’s choice to name it “The Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act” instead of the “Unlimited Shoplifting Act,” voters overwhelmingly approved the measure and soon came to regret it. (Eventually, in a rare feat for California, voters realized their mistake and reversed many of its changes. Prop 36, which passed in 2024 with 68% approval, restored felony penalties for repeat theft and drug offenses.)

No Exit

Much of California’s deathspiralling can be traced back to ballot props. Taxes too high? Take it up with the hospital lobby! Want to buy a house? Unfortunately you’ve got Boomer NIMBYs that will never sell and would rather burn alive than let you reduce their property values! Want to go to a convenience store? Have fun getting stalked by the employees who have to unlock your $8 deodorant!

This is the endgame of California’s ballot prop system: even when everyone agrees a law isn’t working, fixing it requires another statewide campaign. If it takes a decade to end organized shoplifting rings, how confident are you that voters will change less visible (but equally destructive) policies? We’re still waiting for Prop 13’s property tax lock-ins to end despite generations of Californians complaining about home prices.

We like to gripe that the politicians don’t do anything. But circumventing the standard, sluggish legislative process outsources the messy business of governance to faceless unions and NGOs. And the voters? When they see an initiative on the ballot, they don’t read past the title. They watch a couple of ads. They see a billboard saying “No to Corporate Greed.” They say hello to the nice man or woman asking for their signature on the sidewalk. And then they vote. This is what California chose for itself.

In 1911.

— Ryan Hassan

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.