The UK’s drugs regulator is increasingly being frozen out of work with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) according to a press report, dealing a blow to the government’s hopes that it could play a leading role in European drug reviews after Brexit.

With Brexit talks progressing at a snail’s pace and the deadline of March 29th looming, the EMA has been preparing for a “no-deal” situation where the UK becomes a third country and plays no part in the European drugs regulation system.

And the latest report casts doubts about the prime minister’s plans for the UK to continue with its involvement with the EMA after Brexit.

The Guardian reported that the EMA has ceased to appoint experts from the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to oversee centralised reviews of more complex medicines.

These so-called rapporteurs, who can be appointed from any EU country, follow the progress of a medicine as it goes through the EMA’s committee process.

And until the Brexit vote in 2016 the UK played a leading role in this process, providing more rapporteurs than any other country.

But the EMA said that as the Brexit deadline approaches, and with the MHRA looking set to cut its ties with Europe along with the UK and the rest of its agencies, it cannot be confident that MHRA staff will be able to follow the entire review process for recently filed drugs.

EMA reviews usually take around a year, meaning that any drugs that are filed now will still be in the middle of their review when Brexit happens in March.

Rapporteur work being carried out by the MHRA is also being reallocated to representatives from other EU countries.

Martin McKee, professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told the Guardian that the changes are a “disaster” for the UK’s MHRA, which earns around £14 million from the EMA.

In 2016 the EMA appointed 22 rapporteurs to review new medicines, but in 2017 it appointed just six.

Mike Thompson, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), said the process is like the end of a “British success story”.

Pharma companies are already having to build extra labs to batch release medicines made in the UK on the continent.

Thompson added that this is “hundreds of millions of pounds” that could be spent on researching new medicines, but the industry has “no choice” as it has to comply with regulations.

The EMA is in the process of moving around 900 staff from its London offices, to Amsterdam, which will be its new home after Brexit.

The MHRA said in a statement: “We want to retain a close working partnership with the EU to ensure patients continue to have timely access to safe medicines and medical devices. This involves us making sure our regulators continue to work together, as they do with regulators internationally and we would like to explore with the EU the terms on which the UK could continue to participate in the EMA.”

Some elements of the MHRA’s role will change during the Implementation Period. For example, for medicines – as with all areas – the UK will no longer have voting rights in the EMA and EU committees, and MHRA will no longer lead assessments on behalf of the EMA to inform their decision-making process.

“We are currently considering the potential impact of different Brexit outcomes on MHRA. It is important to remember the bulk of agency regulatory work is national, as is its income, said the MHRA.”

A spokesperson for the ABPI said: “The strength of the MHRA has been key to the overall strength of the European regulatory system.”

“The ABPI has been clear that we want to see as close cooperation as possible between the MHRA and the EMA. As we enter the final stages of the Brexit negotiations, we are looking for politicians to make this central to the future UK-EU relationship.”

“Continued cooperation in the long standing systems to protect patient health, control infectious diseases and manage medicine safety is in the best interests of patients in the UK and the EU.”

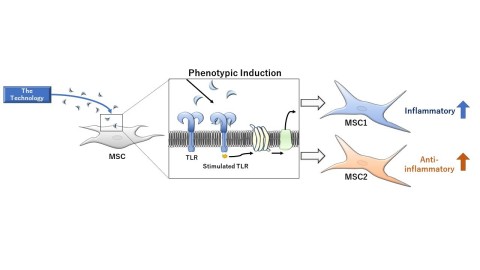

Image of the Technology of MSC1 and MSC2 (Graphic: Business Wire)

Image of the Technology of MSC1 and MSC2 (Graphic: Business Wire)