Surviving a pandemic isn't always the end of the story – some viruses can have health effects that linger on for decades, eventually leading to a range of devastating diseases.

In the 1960s, epidemiologists studying the long-term prognosis of survivors of the 1918 Spanish Influenza began to notice an unusual trend. Those who were born between 1888 and 1924 – meaning they were either infants or in young adulthood at the time of the pandemic – appeared to have been two or three times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease at some point in their life than those born at different times.

It was a striking finding. For while the potential neurological consequences of flu infections have been documented by doctors for centuries – there are medical reports of this which date back to 1385 – the sheer scale of the Spanish Flu, which infected around 500 million people globally, meant scientists could link a heightened risk of disease to the pandemic.

In recent years, an elevated risk of Parkinson's has also been identified in the survivors of outbreaks of HIV, West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis, Coxsackie, Western Equine virus and the Epstein-Barr virus. Neurologists attempting to understand why this happens believe that each of these viruses are capable of crossing into the brain, and in some cases damaging the fragile structures which control the co-ordination of movement, known as the basal ganglia, initiating a process of degeneration which can lead to Parkinson's.

Now scientists are keen to monitor whether the current pandemic will also trigger a higher rate of Parkinson's cases in decades to come.

"We don't know but we need to consider that this could become the case," says Patrik Brundin, a Parkinson's researcher at the Van Andel Institute, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. "There are several studies highlighting that people who have recovered from Covid often have long-term central nervous system deficits including loss of sense of smell and taste, brain fog, depression, and anxiety. The numbers are troubling."

While Sars-CoV-2 can invade brain tissue, the scientific jury remains open on whether it will contribute to neurodegenerative disease. Coronaviruses are generally known as "hit and run viruses", because they tend to cause fairly short disease, even if this proves deadly in some cases. In contrast, DNA viruses such as Epstein-Barr can linger permanently in the body and are more associated with long-term illness.

But there have been some indications in the past there might be more to coronaviruses than we perhaps suspect. In the 1990s, Canadian neurologist Stanley Fahn published a study which identified antibodies to the coronaviruses that cause the common cold in the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson's patients.

Over the past year, scientists like Brundin have been concerned by the emergence of a small handful of case studies describing patients who have developed what doctors term acute Parkinsonism – abnormalities such as tremors, muscle stiffness, and impaired speech – following Covid-19 infection. More research has found that some Covid-19 patients have disruptions in one of the body's most critical systems, known as the kynurenine pathway. This runs from the brain to the gut, and is used to produce a number of crucial amino acids required for brain health. But when it malfunctions, it can lead to the accumulation of toxins which are thought to play a role in Parkinson's disease.

Other neurologists, however, warn it is still far too early to draw any link between Covid-19 and Parkinson's.

The 1918 flu pandemic was still affecting the health of the global population over 40 years later (Credit: Getty Images)

Alfonso Fasano, a neurology professor at the University of Toronto, points out that the cases of acute parkinsonism which have been described could simply involve patients who were already in the early stages of the disease, and the stress of being infected with Covid-19 simply accelerated or "unmasked" the symptoms. "So far, we're talking of about a dozen cases, usually lacking detailed information," he says. "It's true that what we call a post-encephalitic parkinsonism can occur after a viral infection, but not every pandemic is the same. The Spanish Flu was caused by a completely different virus."

However many feel that there is a need for continued monitoring of any Parkinson’s-like symptoms which emerge in people who have previously been infected with Covid-19, in case the coming years reveal a gradual spike in cases.

But Parkinson's is not the only concern. Experts around the world are trying to figure out if Covid-19 will induce a hidden wave of other illnesses, related to the disruption Sars-CoV-2 causes to the human immune system. If this pans out it would have major public health implications, but it could also help us find new ways of detecting these diseases at an early stage, and even pave the way to new treatments and vaccines.

The diabetes dilemma

In the spring of 2020, Francesco Rubino, a metabolic and bariatric surgeon at Kings College London, began to hear an increasing number of reports about Covid-19 patients coming into hospital with unusually high blood sugar levels, even though they had no previous history of diabetes.

At the same time, doctors were also noticing that patients who already had diabetes appeared to be particularly vulnerable to the disease. Rubino was curious to see whether this strange relationship was a sign that Covid-19 was directly impacting the pancreas, a complex organ which contains beta cells for producing insulin, the hormone that helps the body metabolise sugar molecules from the blood.

He set up a global database called the CovidDiab registry to follow these patients, and find out what happened to them. So far they have been tracking 700 cases over the past year, and the hope is that their data might help solve an enduring problem that has intrigued scientists for many years, namely whether viruses can directly trigger type 1 diabetes.

A number of viruses have been linked to the rare neurological condition Guillain-Barré syndrome. One is Zika, which may have led to a spike in cases in 2015 (Credit: Getty Images)

In the past, associations have been made between type 1 diabetes – a chronic condition which typically develops in childhood or adolescence as patients' pancreases become steadily unable to produce insulin – and various viruses such as Coxsackie B, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and mumps. Scientists suspect that these viruses may be capable of infecting the pancreas, either by escaping from the lungs or leaking out of the gut and into blood vessels. In 2015, researchers at the Oslo Diabetes Research Centre discovered a persistent, low grade viral infection in beta cells extracted from pancreas tissue biopsies of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients, but there have been too few cases to establish concrete proof.

"There's been epidemics before which have been associated with new cases of diabetes," says Rubino. "But this link has been based on a handful of medical reports. So we're hoping that by looking at several hundred cases, we might see an association which is more informative."

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, there have already been repeated indications of an abnormal spike in type 1 diabetes cases. By the summer of 2020, hospitals in North West London were already reporting double the number of cases they would typically see, while a paper in Nature earlier this year found Covid-19 survivors in the US were around 39% more likely to have a new diabetes diagnosis in the six months following infection compared to non-infected individuals.

Scientists are now trying to prove that Covid-19 is actually directly contributing to this rise in cases. Shuibing Chen, a stem cell biologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, feels there is evidence which suggests that the virus can attack beta cells, and also generate inflammation in the pancreas and other organs, causing damage to various systems which control blood sugar levels.

"We have detected viral antigens in human pancreatic beta cells in autopsy samples of Covid-19 patients, which supports the role of direct infection," Chen says.

But not everyone is so convinced. Others point out that patients appearing to develop diabetes as a result of Covid-19 could actually be incurring pancreas damage due to intensive steroid treatment while in hospital. Or they may have already been in the early stages of developing diabetes, and Covid-19 again may simply have unmasked the disease.

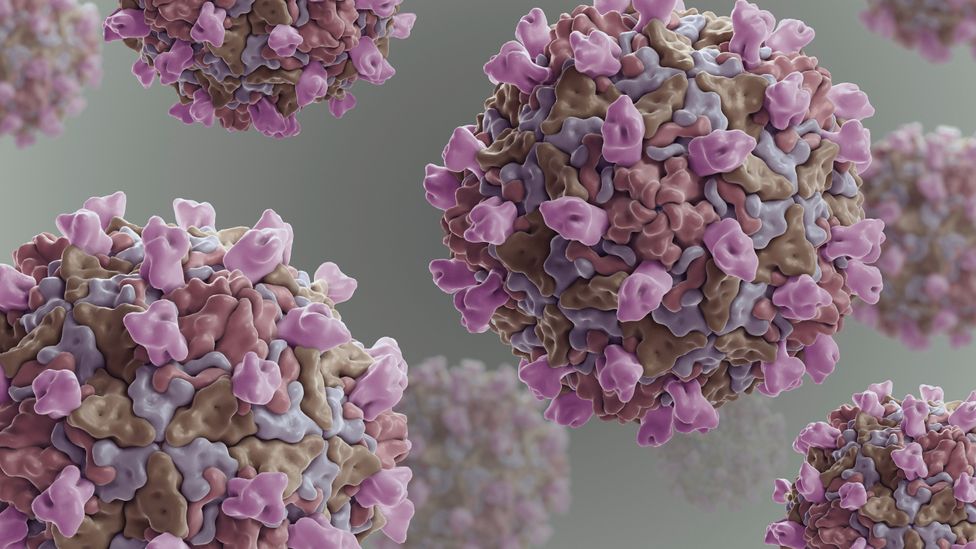

It's thought that certain viruses can trigger an immune response which later increases the risk of a person developing Parkinson's disease (Credit: Getty Images)

"There have been some reports arguing that Sars-CoV-2 can not only directly infect beta cells, but also might kill them," says Matthias Von Herrath, a professor of autoimmunity at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. "A follow up report, however, argues against the notion that it commonly affects beta cells. So the jury as to how specific and dangerous it is in causing beta cell functional loss is still out."

Over the coming months, the hope is that the CovidDiab database will yield some more concrete answers. "We don't expect to be able to answer all the questions, but we hope to learn a lot from these 700 cases which probably represents the largest cohort of virus-related diabetes," Rubino says. "How plausible is it that Covid might have been behind these cases? Is there a direct mechanism and if so, what is it?"

But type 1 diabetes is not the only autoimmune disease being linked to Covid-19. Over the past year, a number of reports have associated Sars-CoV-2 infection with other autoimmune disorders such as Guillain–Barré Syndrome, a rare and serious condition in which the immune system attacks the nerves, causing numbness, issues with balance and coordination, weakness, and pain, and sometimes paralysis..

Scientists believe that patients who have been admitted to hospital with Covid-19 are particularly prone to going on to develop such complications as they are more likely to have auto-antibodies in their blood – a form of protein produced by the immune system which is directed against the body's own tissues, leading to complications. A consortium of scientists at the University of Birmingham are now following a cohort of individuals who had been severely ill with Covid-19, to see how many develop longer term autoimmune problems and what makes certain people particularly vulnerable.

"We can't predict the future," says Russell Dale, who researches autoimmune illnesses at the University of Sydney. "But there are a number of precedents of infectious diseases leading to inflammatory and autoimmune problems."

Diagnostics and vaccines

The prospect of Covid-19 leading to a silent surge of chronic illnesses is a sobering one, but if conclusive links can be established between viral infection and different conditions, it could transform the way we look for and treat many of these diseases in future.

In the case of type 1 diabetes, scientists are particularly keen to study exactly what happens after beta cells become infected with Sars-CoV-2 to see if there is a way to prevent their destruction, and hence halt the onset of the disease before it fully develops. "Understanding the link between viral infection and type 1 diabetes might facilitate early diagnosis and prevention," says Chen.

Coxsackie B virus has been linked to the development of type 1 diabetes – and now scientists are wondering if Covid-19 could also make people more susceptible (Credit: Alamy)

Knut Dahl-Jørgensen, a consultant in pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at the Oslo Diabetes Research Centre, told the BBC his colleagues are initiating a clinical trial to see whether antiviral treatment can help protect the pancreas in children who have been newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.

Chen is also leading a project which involves sifting through a large library of different chemical compounds to see if any can make beta cells more resilient to viral attack. So far they have already identified one particular compound called trans-ISRIB, which appears to be capable of protecting the insulin-producing capacities of beta cells when infected with Sars-CoV-2 in a petri dish. While this is not yet approved by regulators nor tested in humans, and so cannot be used in Covid-19 patients experiencing blood sugar abnormalities at the moment, Chen hopes that in future it could be administered as a preventative drug for vulnerable individuals in the aftermath of infection.

A strong link between Covid-19 and different autoimmune conditions could also encourage the development of protective vaccines against other viruses which have been previously associated with these illnesses. Researchers at the Karolinska Institute, Tampere University, and the University of Jyväskylä have developed a potential vaccine candidate which protects against all six strains of Coxsackie B, and has been shown to prevent mice from developing virus-induced type 1 diabetes.

Gunnar Houen, an immunologist at the State Serum Institute in Copenhagen, believes it could also lead to further investment in vaccines against Epstein-Barr, a virus which has been associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, as well as certain cancers.

"Vaccines are very likely to be effective against Epstein-Barr if given early enough, as most people are infected by this virus during the first one or two years of life," says Houen. "There will be a market for this, since the associated diseases cause as much or even more harm as Covid-19."

In the meantime, scientists hoping that the coming months and years will reveal more about the propensity of Covid-19 to trigger each of these illnesses.

"All these questions will not be answered tomorrow, or in the next couple of months, but over the next year we hope to be able to look into this data and begin to answer certain questions, start to see some patterns and maybe have some answers," says Rubino.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220127-could-covid-19-still-be-affecting-us-in-decades-to-come