Viruses are fascinating. Watching the twists and turns of SARS-CoV-2 mutations and their effect on the entire planet has made it easy to appreciate the raw evolutionary ability of a novel viral pathogen. But polio… there’s a virus with some serious history on its side, from Egyptian carvings to FDR’s wheelchair, and it’s still grabbing headlines.

The latest:

It’s easy to feel a bit of panic in the air. A young man was paralyzed in the New York City suburbs. Poliovirus was found in the wastewater of 8 boroughs of London. What in Sam Hill is going on here?

To understand, I had to do some reading. Whatever little bit I learned about polio in med school I promptly forgot, since, well, no one sees polio anymore. Vaccines made the worst-case, 1 in 200, outcome of a poliovirus infection, paralytic poliomyelitis, virtually disappear. Not totally, however, and that’s where this virus and the vaccines that prevent it get so interesting. So much so that it’s worth breaking it down a little, to get a better handle on why it popped up in a New York City suburb, and what that means to us going forward.

Interesting Polio Vaccine Fact #1: The Salk vaccine, generally known as the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), developed first and used exclusively in the US since 2000, is incredibly effective (99%+) at preventing paralytic poliomyelitis but does not convey mucosal immunity, and therefore does little to reduce transmission of the poliovirus.

Yes, a true life-saving, disability-sparing vaccine, and one with virtually no adverse effects. However, the inactivated virus triggers a marvelous immune response in the blood without establishing immunity in the gut. Since poliovirus is a fecal-oral route pathogen — meaning viral particles are not passed in tiny aerosols from our breath, or large droplets from a cough, but rather in tiny bits of fecal matter that make their way onto hands, or into the water supply, and then into mouths — the poliovirus can readily spread itself in its usual manner among a population entirely immunized via the IPV vaccine. Remember that, Americans! Lest we think our adult selves too clean for such a lowly route of transmission, recall that we are a “wipe right/shake right” society, and that not every food preparer employs ideal hand washing technique in the restaurant bathroom.

When you see Science reporting like this, you might want to unsubscribe; this quite misconstrues the protection actually afforded to a country well-vaccinated via IPV:

The New York Times offered a similarly poor characterization; it’s fair to fault communities with low IPV uptake for putting their populace at risk, but not for spreading the disease:

Interesting Polio Vaccine Fact #2: The live attenuated Oral Polio Vaccine, developed by Dr. Albert Sabin, is cheap, easy (taken as a few drops of liquid by mouth), and remarkably effective both at preventing infection in the gut as well as severe neurological disease, but has an Achilles heel: it can mutate back into a virulent form of polio!

This is the vaccine that has virtually eliminated wild-type polio from the globe. In the US, it was used exclusively for decades until polio was essentially gone, and then IPV reintroduced. Why bring back the older, more expensive IPV? The faint risk of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP). Very rarely — in the 1 in 2-3 million range — people who receive the vaccine, often immune-compromised, brew up a case of paralyzing poliomyelitis if the virus mutates into a pathogenic form and attacks the nervous system. Sometimes, too, especially in communities employing the OPV vaccine but with lower rates of acceptance, a strain could circulate among the community and acquire mutations over a year or two that would revert it back to a pathogenic strain, so-called “circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus” (cVDPV). The treatment, at least until 2020, was to give everybody more OPV until herd immunity is built up and hope to avoid more vaccine-associated or vaccine-derived cases of polio!

Interesting Polio Vaccine Fact #3: There are 3 types of wild poliovirus; type 2 has been eradicated (and recently type 3 as well) through the global OPV campaign, but type 2 most easily mutates back into a virulent form from the OPV vaccine, meaning that no wild type 2 poliovirus is now in existence, but most cases of actual poliomyelitis are caused by vaccine-derived type 2 polioviruses.

This has led to a wild cat-and-mouse game between vaccine-derived virus and vaccine. Bivalent (type 1 and 3 only) OPV was developed, since wild type 2 was eliminated from the globe and the type 2 strain in the vaccine was so problematic. Great — except when a vaccine-derived type 2 strain begins to circulate in an undervaccinated community! Neither existing option was appealing: either bring in IPV (not always possible in the developing world) only to prevent paralytic disease without breaking transmission chains, or saturate the community with the old trivalent OPV vaccine and risk more of the same problem in the future. The solution to this cycle has been the development of a modified type 2 monovalent OPV (mOPV2), reformulated to greatly reduce the risk of mutating into a problematic form. This is the new band-aid for outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus since 2020; but of course will not protect against the type 1 wild poliovirus still found in Afghanistan and Pakistan, nor the type 3 vaccine-derived poliovirus found circulating in Israel that led to paralysis in a 3 year-old earlier this year.

Speaking of Israel, it appears to be a poorly-kept secret (since the New York Times reported it) that the young man now paralyzed with poliomyelitis from a type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus is a member of the Orthodox Jewish community. Yes, that Orthodox Jewish community in Rockland and Orange Counties, with the notoriously low rate of childhood vaccinations (around 60%) that went through a measles outbreak in 2018-19.

If we were in Africa or India, the sensible public health response would have been to bring mOPV2 into the community health centers, and have the rabbis begging their synagogues to have everyone immunized with this ideal vaccine to both stop the spread of this strain and prevent severe disease. Instead, in a move that appears to leave virologists somewhere on the spectrum between bemused and bedeviled, we stick with IPV, allowing transmission to continue almost unabated. But at least we publicize it!

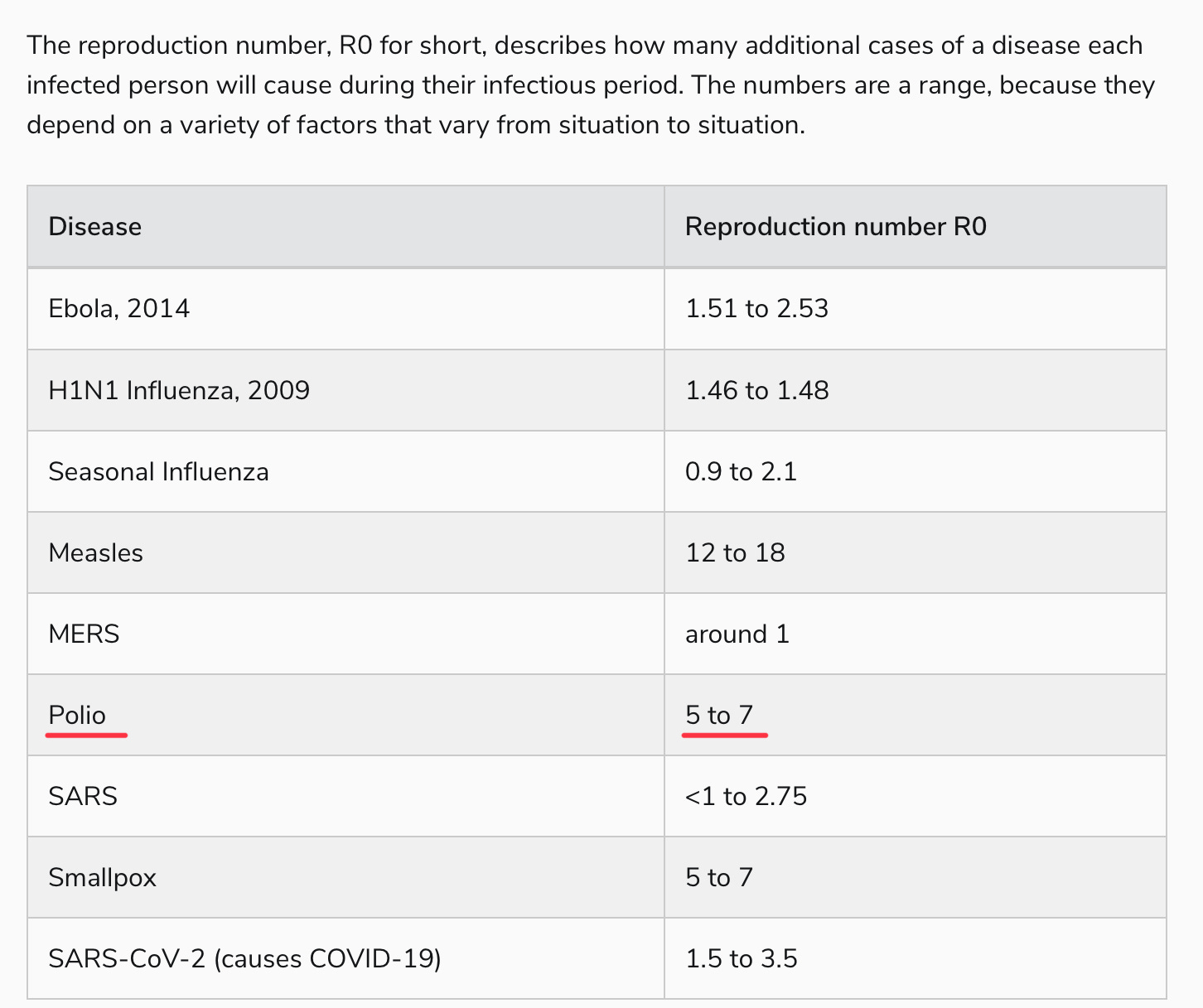

The problem, of course, is that while paralysis will be prevented in people, like the gentleman pictured above, who get their IPV vaccine, there can be no herd immunity via these vaccines for those who can’t be persuaded to roll up their sleeves, given the lack of mucosal immunity. From what I can tell, this creates a problem; observe the reproductive number of polio in a non-immune community:

Yes, polio is right up there with our most transmissible pathogens, probably not far from our new friend, Omicron BA.5. Perhaps this is outdated information, calculated in an era of open sewers, or simply overstated. But hearing virologists talk about polio, it’s generally with a sense of, “oh, everyone just gets it” in outbreak conditions, which is why a paralytic polio rate of 1 in 200, or even 1 in 1000, is so problematic.

That, to me, is the mystery of these recent vaccine-derived polio outbreaks. The protection against polio infection — not paralytic poliomyelitis, mind you, just the majority of poliovirus infections which are asymptomatic (around 70-75%) or the remainder that are more flu-like — should be incredibly low, at least among those born after 2000 in the U.S. who are not blessed with the superior immunity of OPV recipients. How does a virus with an R0 >5 circulate for months in places like New York and London without tearing through the kids in a densely-packed, non-immune community, and not rapidly spread to other communities?

https://doctorbuzz.substack.com/p/the-new-polio-outbreak-is-bad-but