Are the additives in our food quietly conspiring against our health? A new French study dives into the tangled web of food additives, not as individual villains, but at their gang affiliations. Do these combinations, a rogue’s gallery of emulsifiers and colorants, conspire to nudge us toward diabetes? The research explores whether a threat lies in the synergy of the ingredients we blend, bottle, and blissfully consume.

“Don’t eat anything with more than five ingredients, or ingredients you can't pronounce.”

– Michael Pollan

While there is an association between “ultra-processed foods” (UPF), which is an ambiguous term, and metabolic dysfunction of glucose and fat metabolism (resulting in an associated increase in diabetes and cardiovascular disease), science has yet to identify a smoking gun. A new study suggests that we are too reductive and that it is not additives individually but in combination, acting as synergistic smoking guns, that may be the culprit.

The data comes from the French, specifically the NutriNet-Santé prospective study investigating the relationship between nutrition and health. It features our epidemiologic friend, the food frequency questionnaire, completed every six months, and categorizing the food intake for three non-consecutive 24-hour intervals. The presence and amounts of food additives were estimated based on those questionnaires.

Using a mathematical technique that identifies real-world combinations without discernable bias (Non-Negative Matrix Factorization), the researchers identified five patterns of additive combinations. These patterns provide the categorizing tool for their real investigation of the impact of additive combinations on the onset of diabetes.

Their modeled findings were adjusted for known risk factors for type 2 diabetes, including demographic, lifestyle, socioeconomic, and dietary. The dietary variables included energy intake (excluding alcohol), saturated fat, sodium, dietary fiber, alcohol, and added sugars. The study’s 108,643 participants (79.2% women, median age 41.2 years) were tracked through a median of 5 dietary intervals each. Diabetes was self-reported or identified from insurance or health datasets. Seventy-five food additives consumed by at least 5% of participants were included in the five patterns of combination identified.

Mixture 1: The Leavening Blend brings together ingredients commonly used in baked goods and snack foods, classic UPFs, to help them rise, retain moisture, and stay shelf-stable.

Mixture 1: The Leavening Blend brings together ingredients commonly used in baked goods and snack foods, classic UPFs, to help them rise, retain moisture, and stay shelf-stable.- Mixture 2: The Thickener-Stabilizer Combo adds texture, viscosity, and stability to processed foods. They appear frequently in broths, dairy desserts, sauces, and spreads where consistency and mouthfeel are essential.

- Mixture 3: The Dispersed Fortification Set is lightly scattered across various foods and provides vitamin enrichment, coloring, or anticaking. They can be found in salt, energy drinks, and cocoa powder.

- Mixture 4: The Emulsifier-Enhanced Snack Mix is a more enhanced version of Mixture 1, contributing to texture, structure, and shelf life.

- Mixture 5: The Sweetened Beverage Profile the additives in sugary and artificially sweetened drinks – the great Satan. The mix includes acidifiers, colorants, gums, and the ever-sinful non-nutritive sweeteners.

One thousand one hundred thirty-one individuals had the onset of type 2 diabetes over roughly 7.7 years. Consumption of Mixture 2 showed an 8% increase in diabetes, while Mixture 5 resulted in a 13% increase. None of the other mixtures showed any association with diabetes. [1] In a subsequent mediation analysis, where other factors were weighted to ascribe their contribution to the outcome of diabetes, Mixture 2 had a slight weighting of 18%. In comparison, this increased to 42% for Mixture 5, sweetened beverages. [2]

A pinch of bias

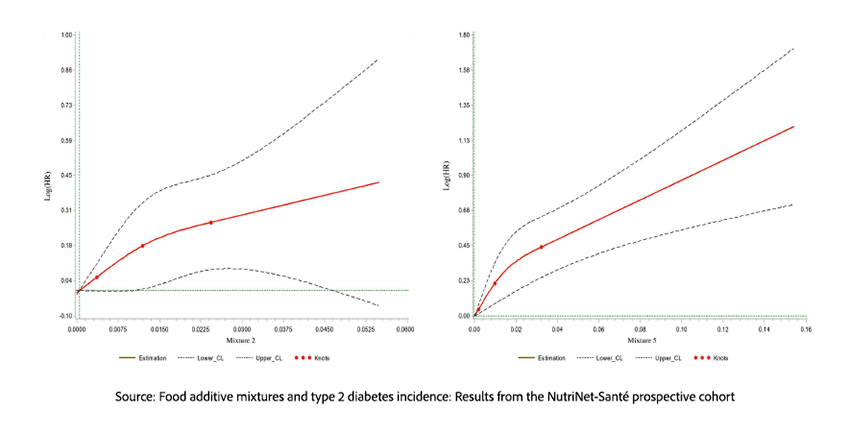

The researchers should be applauded for being holistic and considering the impact of ingredients rather than a single ingredient – after all, we eat the mixture, not the components. More importantly, the researchers acknowledge, at least in one sentence, that additives can be antagonistic to the onset of diabetes. But a desire to “go big or go home” persists. The graph showing the dose-response impact of Mixtures 2 and 5 forcefully demonstrates an upward progression.

But the vertical scales are quite different. The estimate of the impact of Mixture 2 barely rises to the level of the lower confidence level for Mixture 5, consistent with its numerical lesser impact, an 8% increase in the risk of the onset of diabetes vs. 13%, which while not negligible is certainly not nutrition’s smoking gun.

This is a bit of graphic puffery, which I suggest is the case with their conclusion.

“In conclusion, the results of this large population-based study revealed positive associations between widely consumed food additive mixtures and a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes. … these findings provide support for the public health recommendation to limit exposure to UPF and their nonessential food additives.”

Of course, it also identified non-associations. Finally, a closer inspection of the mixtures raises the question of what the term additive suggests. In several instances, those additives are naturally occurring ingredients that you might find in the kitchen of a foodie or more culturally diverse eater.

Of the components in Mixture 2, only three might be considered manufactured: polyphosphates, modified starches, and potassium sorbate, a preservative. The modified starches are derived from plants, and the potassium sorbate is a potassium salt of sorbic acid found in berries. Despite their names, the remaining additives, pectin, guar gum, carrageenan, xanthan gum, and curcumin, are all naturally sourced. In the NOVA classification, they would be largely considered ingredients.

The acidifiers in Mixture 5, citric and malic acid, are naturally derived. Sodium citrate is a salt of citric acid, a natural component of citrus fruit; while phosphoric acid can be found in nature, it is typically synthesized for industrial production. The emulsifiers are naturally sourced, as are two of the three colorants, anthocyanins, found in berries, grapes, and cabbage, and paprika extract. Caramel coloring is made by heating sugars in the presence of ammonium and sulfite. The artificial sweeteners are synthesized from amino acids in the case of aspartame and sugar in the case of sucralose.

Taken as a group, these additives “of concern” are most often natural substances, so it is hard to argue that ultra-processed foods (UPF) are some technological nightmare. Many of them are used by “home cooks” to serve the same purpose they do in UPFs, corn starch, and pectin, both thickeners and curcumin, an extract of turmeric, is a “wellness fav,” and is often found in the spice rack. Lemon juice is a common “acidifier” used to brighten the flavor of foods. My point is that while the research nudges us towards concern about additives in UPFS, by the numbers and our use in the home, additives are not nutrition’s smoking gun. More critically, their presence in our food can be an antagonist to metabolic disease or have no impact. We just do not know, and if we are honest, we may never disentangle the role of diet from all the other known variables that affect our health.

Ultimately, this study hints at the complexity of dietary impact, where some additive blends show a modest increase in diabetes risk, but others seem benign. When stripped of their chemical aliases, most of these “ultra-processed” additives are as exotic as lemon juice or cornstarch. Food is more than the sum of its parts, and science rarely delivers in five ingredients or less.

[1] The supplemental information included graphics demonstrating Mixture 1 and 4 were associated with a slightly lower incidence of diabetes, making the point that synergisms are not always in a positive direction. To call the additives preventative would be a “bridge too far.”

[2] The mediation was greater for non-nutritive sweeteners than for sugary beverages, raising the question of whether weight and concern over the onset of diabetes might be significant unreported mediators.

Source: Food additive mixtures and type 2 diabetes incidence: Results from the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort PLOS Medicine DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004570

Dr. Charles Dinerstein, M.D., MBA, FACS is the Medical Director at the American Council on Science and Health. He has over 25 years of experience as a vascular surgeon. He completed his MBA with distinction in the George Washington University Healthcare MBA program and has served as a consultant to hospitals. While no longer clinically active, he has had his writing featured at KevinMD and Doximity.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.