Fentanyl overdoses can happen in minutes, and the usual tools respond after the damage is already underway. A proposed vaccine tries a different approach: keep fentanyl tied up in the bloodstream so less reaches the brain. According to an article in Wired, a first human trial is coming soon, which should tell us whether the rodent results hold up in people.

A new article that appeared on the Wired website notes that we'll soon know whether a vaccine designed to prevent fentanyl overdoses in people will do the job. Let's take a look at some of the science.

If you’re vaguely familiar with chemistry, biochemistry, or immunology, you might be wondering how anyone could make a vaccine that neutralizes a small molecule like fentanyl. After all, most standalone immunogens that reliably elicit an antibody response are proteins on the order of thousands of daltons or more. Fentanyl is only about 336 daltons, roughly 15 to 30 times smaller by molecular weight than a small protein. (A dalton is a unit of molecular mass, roughly the mass of a hydrogen atom.)

Hapten formation

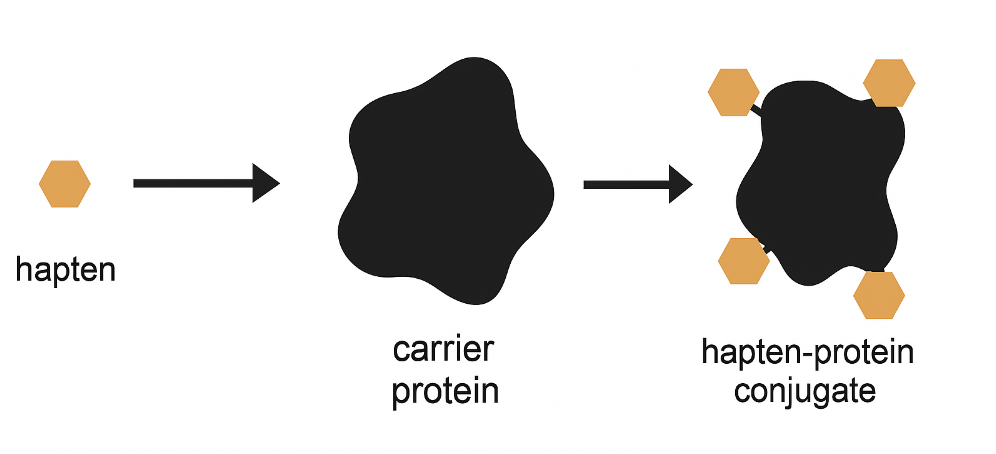

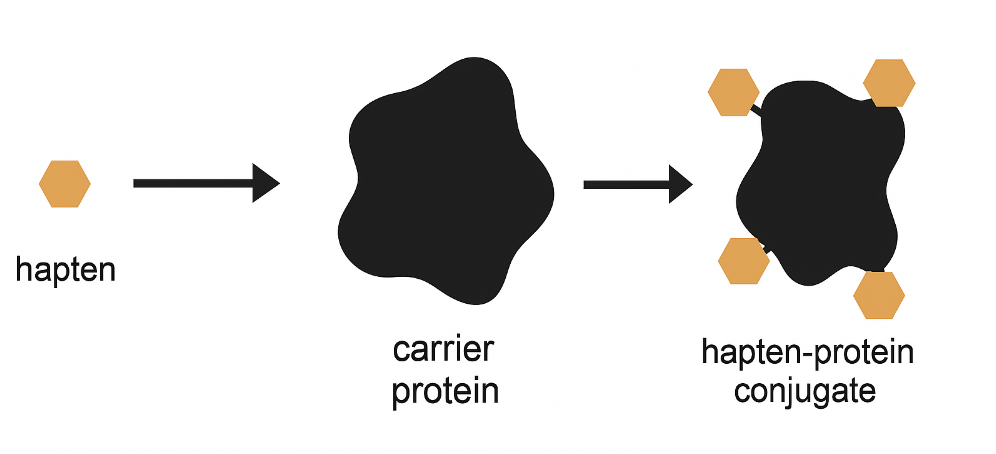

So how do you get a molecule that small to trigger immunity? The key is to treat fentanyl as a hapten – a small molecule that antibodies can recognize, but that usually does not generate a strong immune response on its own. Researchers chemically link a fentanyl-like hapten to a much larger carrier protein, often albumin or a carrier made from inactivated diphtheria toxin—a protein that’s been used safely in vaccines for decades

The resulting hapten–carrier conjugate is immunogenic and can elicit antibodies that bind fentanyl. In vehicular terms, it’s like strapping a tricycle to the front of a truck: suddenly it’s big enough to get noticed (not something you'll see every day). Most important: fentanyl, a small molecule, easily passes from the blood to the brain. Strapping it to a molecular truck can greatly reduce this—and in the best case, prevent most of it from reaching the brain.

Figure 1. Schematic of hapten–carrier protein conjugation. Multiple hapten molecules (small orange symbols) are covalently attached to a larger carrier protein, forming a multivalent hapten–protein conjugate that can elicit anti-hapten antibody production when used as a vaccine antigen.

Later, if fentanyl enters the bloodstream, those antibodies can bind to it and limit its ability to reach the brain. This can blunt or prevent both the euphoric effects and the respiratory depression that causes fatal overdose. Over time, the antibody–fentanyl complexes would be cleared by the body.

It sounds promising. The real question is whether it will be useful in real life.

Why it might work

It has worked in mice and rats, suggesting that human benefit is at least plausible. In one set of rat experiments, the shot blocked 92–98% of fentanyl from entering the brain, prevented the drug’s usual behavioral effects, and the protection lasted at least 20 weeks.

In a different kind of rat study where animals could choose fentanyl or food, vaccination shifted behavior away from fentanyl, consistent with the drug becoming less “rewarding.” Similar, though smaller, potency shifts have also been reported in mice, where vaccinated animals needed several-fold more fentanyl to produce the same effects in standard tests.

Taken together, these results are a strong sign that antibodies really can intercept fentanyl in the bloodstream before it can do much damage.

Why it might not work

In addition to the usual species differences that plague drug discovery, there are additional practical reasons a fentanyl vaccine might have limits.

- It may protect against some fentanyl analogs, especially ones that are structurally similar to fentanyl, but not others.

- It would not protect against heroin or other morphine-based opiates.

- Even if it protects against a certain fentanyl exposure, a large enough dose would likely overwhelm the available antibodies and allow some fentanyl to reach the brain.

- How large is “large enough” in humans isn’t yet known.

- And even if it works perfectly against fentanyl, it would not prevent overdose from other drugs—whether other opioids or mixtures that include non-opioids.

Would it be used?

Maybe. In practice, the vaccine might be appropriate for teens, who may unintentionally run into something like fentanyl-spiked cocaine or methamphetamine on the street. Would they take a vaccine for this reason? Hard to say. Other candidates might be to protect people who are addicted and now receiving treatment.

One believer is Collin Gage, the cofounder and CEO of ARMR Sciences, a company focused on developing a vaccine against fentanyl. He sees the potential of a medicine that will prevent an overdose, not treat it.

"It became very apparent to me that as I assessed the treatment landscape, everything that exists is reactionary... I thought, why are we not preventing this?”

Bottom line

So, is this a breakthrough? Maybe. The concept makes sense, the animal data are encouraging, and the limits are pretty obvious, too. Now we get to the part that matters: what happens in people—and whether human behavior is predictable enough for it to matter.

Even a vaccine that works biologically won’t help much if the real-world behavior is “take more,” “take something else,” or “take bigger risks.” The human trial will tell us whether this is a useful new tool, or just a clever idea that looks better on paper than it does in real life.

Dr. Josh Bloom, the Director of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Science, comes from the world of drug discovery, where he did research for more than 20 years. He holds a Ph.D. in chemistry.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.