by Randall Bock

Autism’s apparent explosion cannot be understood without first clarifying what the term now encompasses. What was once a rare, severe neurodevelopmental condition, often accompanied by intellectual disability and institutionalization, has expanded into a broad diagnostic spectrum that includes many individuals with normal or exceptional cognition and minimal functional impairment. This diagnostic elasticity, combined with deinstitutionalization, shifting social expectations, and powerful policy incentives such as mental health parity, has dramatically altered who is counted and why. Genetics and environment both matter, but neither operates in isolation; traits can persist and amplify through assortative mating and selection in a cognitively specialized economy without requiring increased reproduction among the severely affected. Regression narratives and prevalence curves, when stripped of definitional context, invite monocausal explanations that medicine has long known to be false. The real crisis lies less in a sudden biological catastrophe than in the convergence of diagnostic expansion, incentive structures, cultural signaling, and policy decisions that reward labeling while obscuring causation

My recent essay, “The Truth About Autism and Vaccines Doesn’t Suit Either Side”, in The Daily Sceptic, prompted thoughtful responses. This follow-up addresses certain objections and explains why diagnostic expansion matters before causation can be responsibly assigned.

Q1. You entered autism research only recently. Others have studied this for decades. Why should your view matter?

My relative late arrival to autism research does not mean late exposure to autism itself. I practiced street-level primary care for decades. I came to autism as an independent, freelance, unfunded physician trying to understand what the word now means -- not as an advocate seeking a culprit. The root word of “doctor” is “teacher” and I take that job seriously, to wit: in his preface to his republishing my “Unraveling Autism’s Surge”, Robert W Malone MD, MS stated, “Dr. Bock does an excellent job of making the vast array of information available on autism comprehensible.”

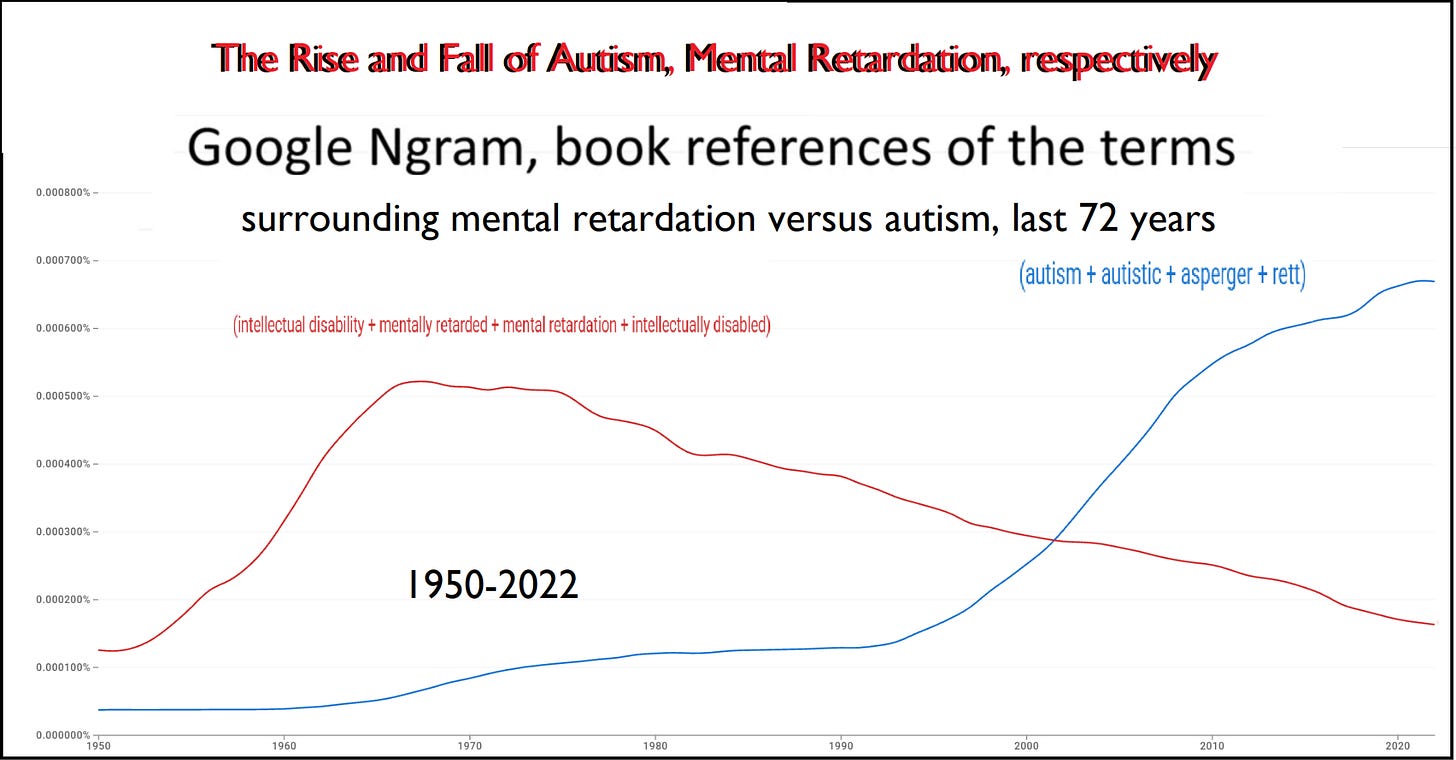

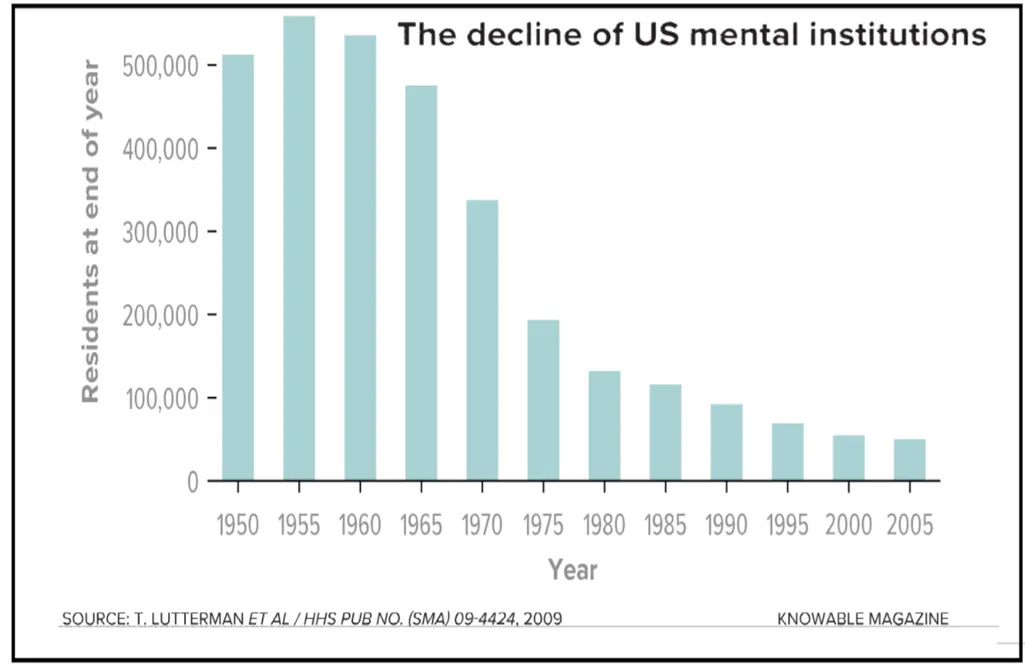

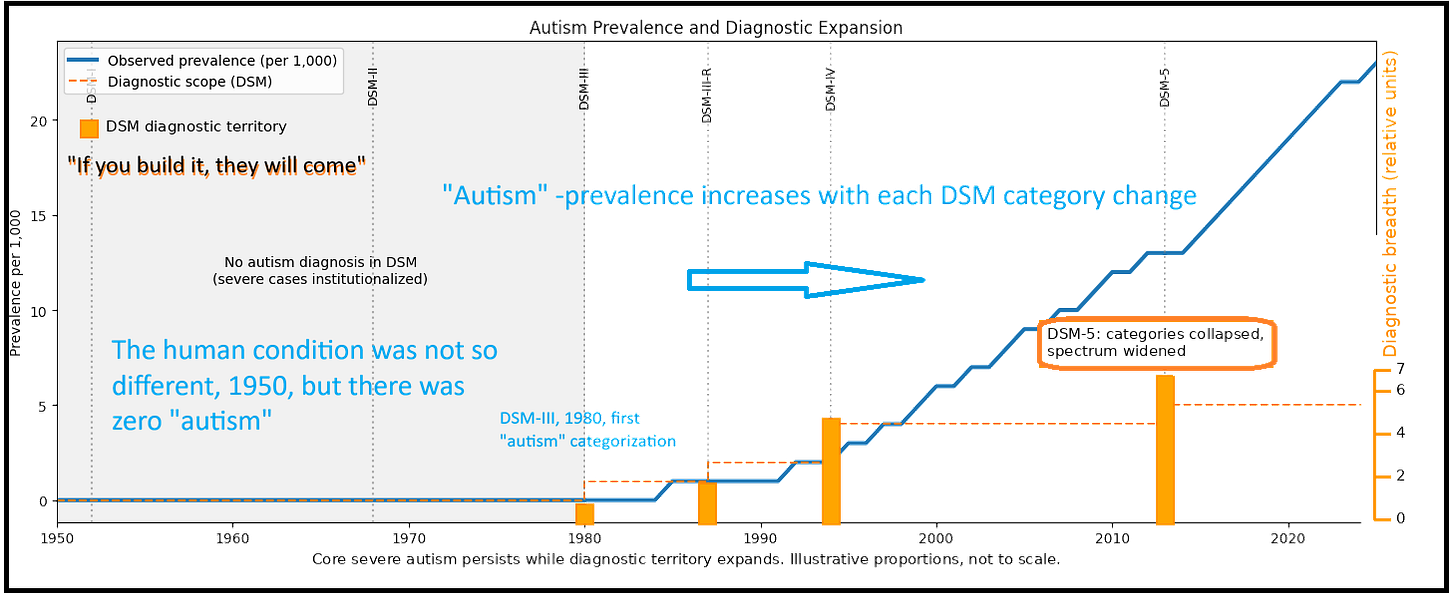

In the mid-20th century, autism was narrowly defined and often subsumed under intellectual disability; however, mental retardation and autism terminology have had (to mix metaphors) a “changing of the guards”, effecting a “new label on an old bottle” (of the underlying pathology)...

...made more urgent by deinstitutionalization. Those erstwhile separated are now present in schools, communities, and datasets. That alone can generate dramatic apparent rises without invoking a novel toxin or uniform injury.

I graduated medical school in 1981; thus experienced these changes (albeit glacially, and indirectly): having seen the institutionalized population (late 70s during medical school), and then (once released) through offshoots from my family-practice patients.

Q2. Autism is not genetic in the way hemophilia is. All disease involves genetics. Why emphasize genetics at all?

Genetic contribution does not mean genetic determinism, nor does it deny environmental influence. Hemophilia is a single-gene disorder with near-deterministic expression. Autism is not. It is polygenic, heterogeneous, and probabilistic. Framing autism as purely environmentally-caused collapses that complexity and invites monocausal thinking.

Q3. But if autism prevalence is truly rising, wouldn’t a genetic condition be expected to dwindle unless the affected group reproduces at higher rates?

This claim rests on an overly narrow model of genetic transmission. It assumes that only the most severely affected individuals matter for prevalence, and that genetic traits behave like a single Mendelian defect that either expands or disappears based solely on fertility at the extremes. That assumption is false.

Genetic traits can persist and even amplify without increased reproduction among the severely affected through well-described mechanisms: heterozygous advantage, assortative mating, and selection within a cognitively specialized economy. Traits that are adaptive in one context can become maladaptive at the tails, particularly when combined across generations. Sickle-cell disease persists because the heterozygous state confers protection against malaria, even though the homozygous form is lethal. Autism-associated traits may follow a similar pattern.

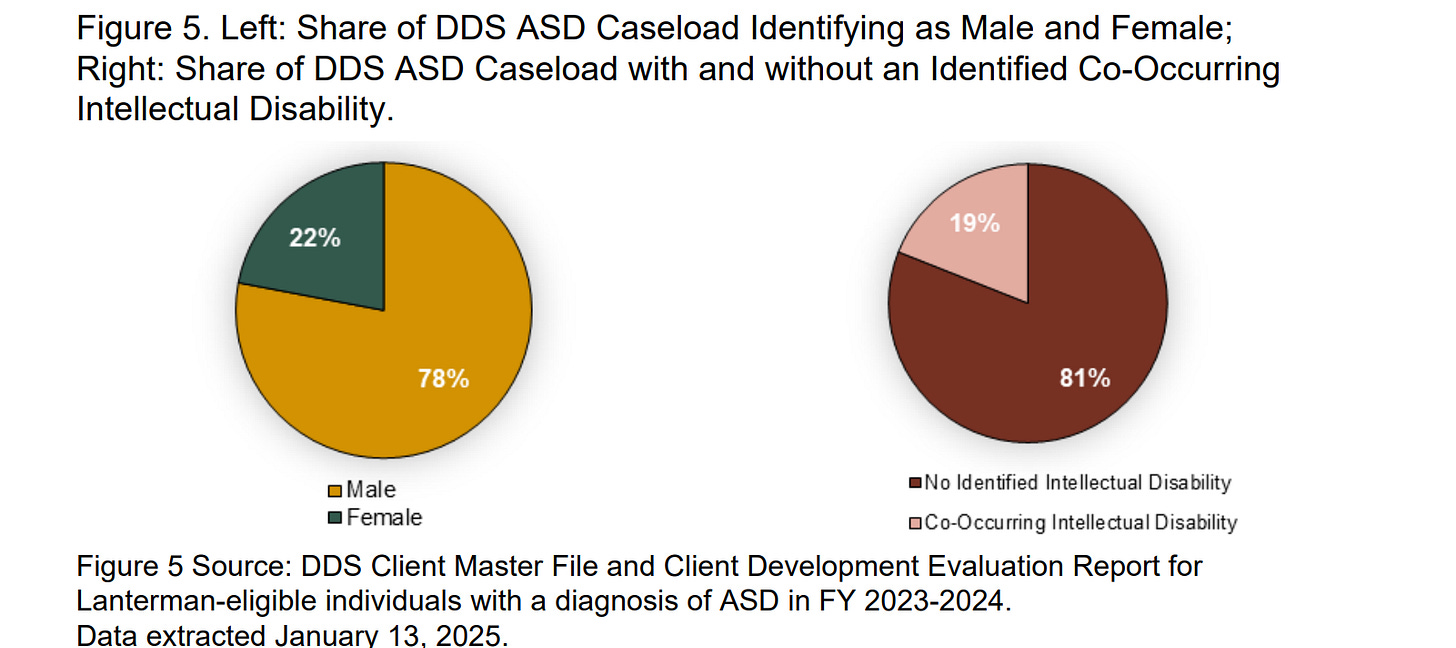

However, genetics alone cannot explain what we are currently labeling as an “autism epidemic.” The diagnostic object itself has changed. Autism has progressively detached from what was once labeled intellectual disability.

King and Bearman’s study stopped 2005, subsequent years have shown even further “drift” for autism from mental retardation (roots), from 60% coincidence 1993 to only 19% ,2023.

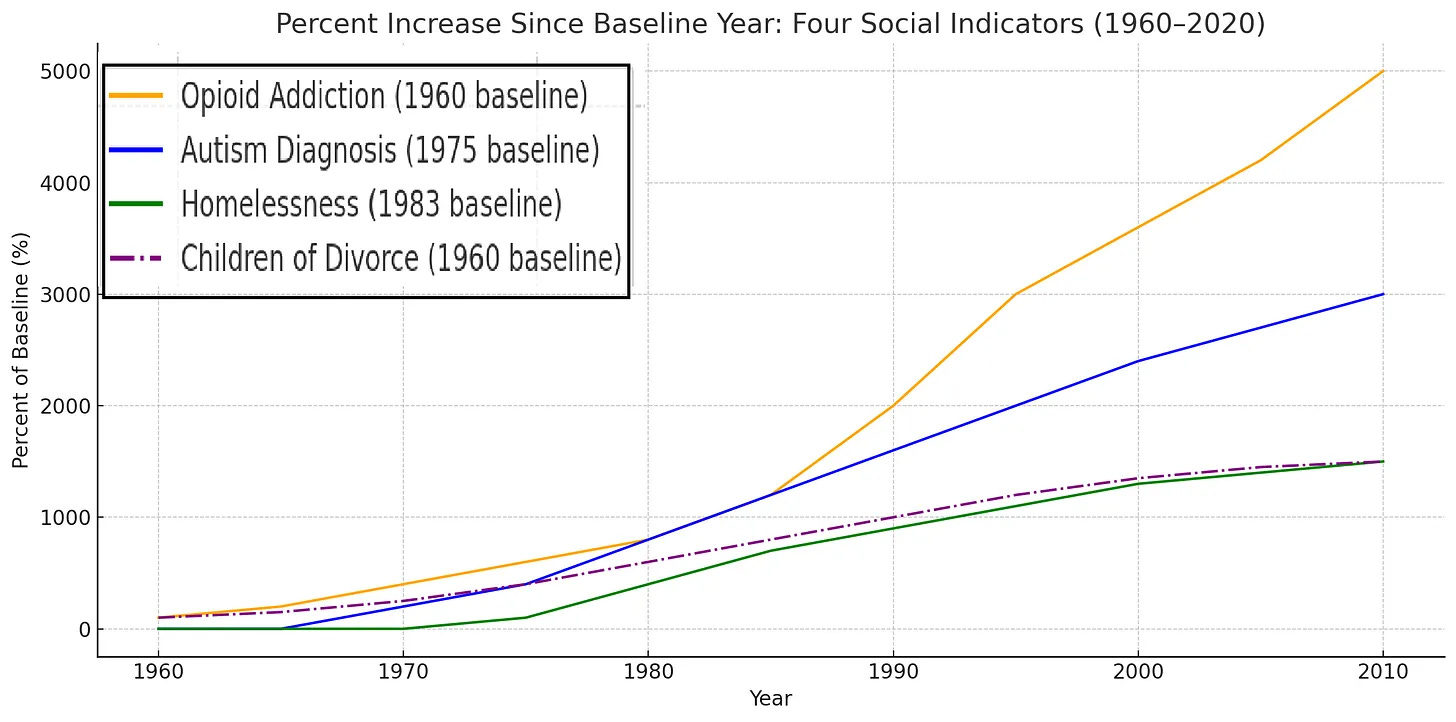

Autism’s rise also parallels increases in homelessness, opioid addiction, and other forms of psychiatric distress; lately “sexual dysmorphia”. These synchronized trends strain the plausibility of a single genetic or toxic cause acting uniformly across domains. They instead point toward shared structural drivers: diagnostic inflation, altered social expectations, incentive realignment, and expanded funding tied to labels.

Policy sits at the center of this shift. Mental health parity and broadened eligibility criteria opened financial channels, to which schools, health systems, and service providers respond (predictably). Severe autism continues to exist much as it did before it had a name; however, “parity” created a powerful feedback loop. “Neurodivergent” -labels unlock accommodations, staffing, funding, and social recognition. Students enjoy extended testing time, special dispensations, individualized plans, and preferential housing.

Similar dynamics are evident abroad. Rogers is correct to warn about the costs; however, he errs is in attribution. The drivers lie in the interaction of diagnostic elasticity, financial incentives, cultural signaling, and institutional policy. Without confronting those forces, neither prevalence curves nor cost projections can be interpreted honestly.

Q3. Autism rates are rising in real children. This is not diagnostic drift.

Some increase may be real. Diagnostic expansion is also real.

Autism in the 1980s referred primarily to a rare, severe neurodevelopmental condition, often with intellectual disability. Today it encompasses a broad spectrum, much of it without intellectual disability, and increasingly without functional impairment. Educational eligibility, service access, and cultural framing all interact with diagnosis.

Treating these eras as equivalent and inferring a single cause commits a category error. Sequence matters. Definition precedes causation. Without clarifying what is being counted, prevalence curves mislead. From my Unraveling Autism’s Surge:

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 formalized autism as a developmental disorder, shifting it from a rare condition to a spectrum encompassing a wide range of behaviors. This change, coupled with parental advocacy, drove earlier screening -- often at 18–24 months -- and more inclusive diagnoses. By DSM-4 (1994), Asperger’s syndrome and PDD-NOS were included, capturing individuals with average or above-average intellect. DSM-5 (2013) dropped Asperger’s as a named diagnosis. Importantly, DSM-5 also removed the prior exclusion that had prevented an individual from being diagnosed with both ASD and ADHD, conditions once considered mutually exclusive.

An analogy may help. Lithuania once governed a vast empire. An irredentist or revanchist might still point from the Baltic toward the Black Sea and insist that all of it counts as “Lithuania.” Others would limit the definition to the historic core.

Autism faces the same problem. Without distinguishing the core from the annexed territory, prevalence curves conflate boundary revision with biological change. Autism, 2026 resembles 17th-century Lithuania; whereas more realistically, geographically, taxonomically it should be on par with today’s smaller Baltic state.

Autism’s modern expansion has produced both irredentist and revanchist postures. Irredentism appears in the claim that ever-wider behaviors were always “really autism,” merely unrecognized until diagnostic borders expanded. Revanchism emerges when that expansion is paired with grievance and moral urgency, demanding rupture, punishment, or vast compensation rather than disciplined inquiry.

These postures are reinforced by incentives. In the UK, Special Educational Needs is vulnerable to exploitation. In the US, similarly, diagnoses unlock funding (and fraud).

Q4. Thousands of parents report regression after vaccines. Are you dismissing that? How does that fit with a genetic or developmental model?

Regression narratives deserve attention. They are not, by themselves, dispositive of mechanism. Regression may reflect recognition of underlying vulnerabilities at developmental stress points rather than de novo injury. Neurodevelopment is dynamic. Schizophrenia presents late without requiring a late toxin. Autism may involve earlier vulnerabilities revealed under load.

A developmental-genetic model does not require that autistic traits be obvious at birth. Many neurodevelopmental conditions involve latent vulnerabilities that become apparent only at specific developmental stress points: language explosion, social reciprocity demands, executive-function loading, or sensory integration thresholds. When expectations change, underlying differences are revealed.

A child who appeared typical at 12 to 18 months may have been operating within a narrow behavioral bandwidth that masked emerging differences. As demands increase, compensation fails, and the divergence becomes visible. That feels abrupt to parents, but it does not require a new pathological event.

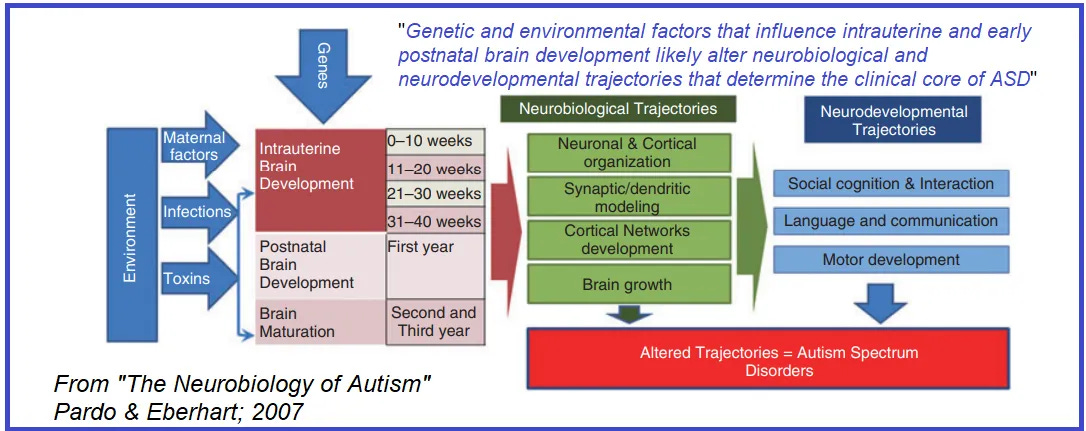

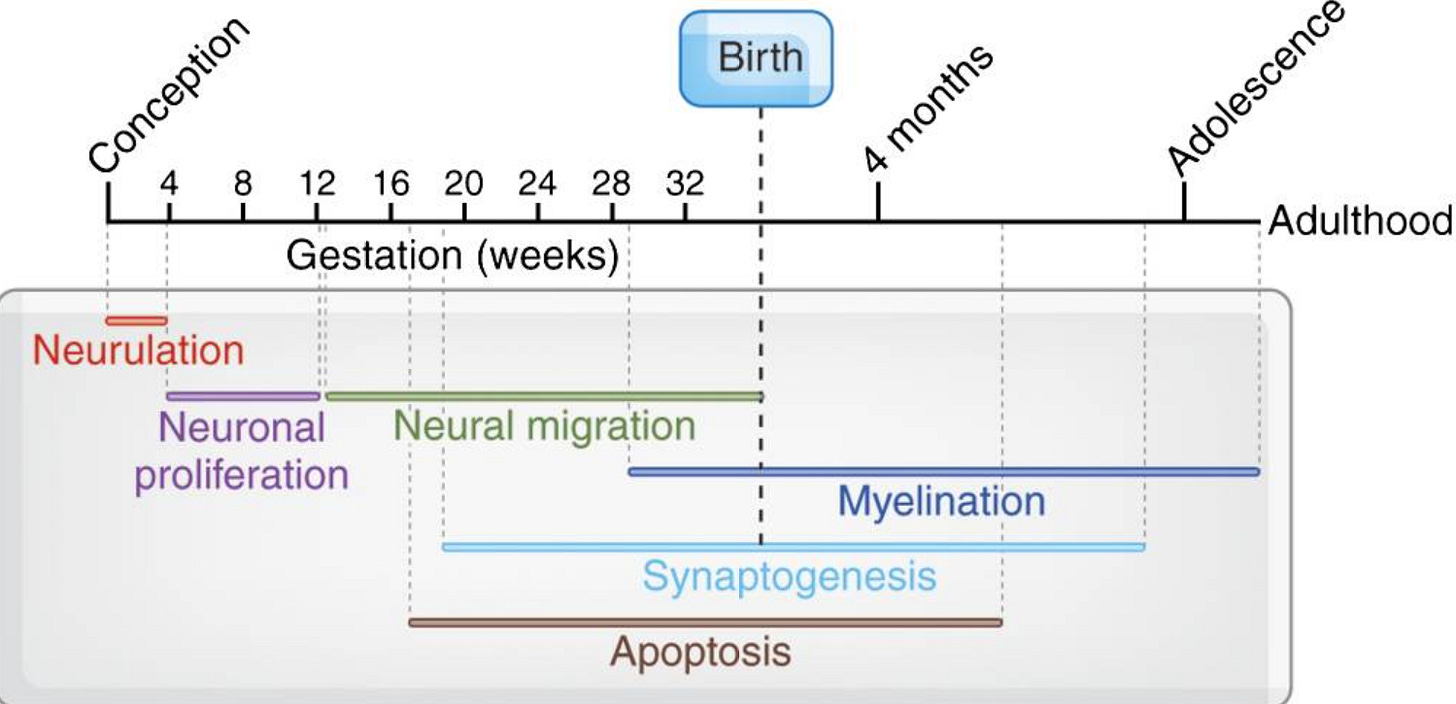

Biology supports this interpretation. The core architecture of the brain is laid down early, largely during embryogenesis and the first months of life. Neural patterning, migration, and large-scale circuit organization occur on a compressed time scale measured in weeks, not years.

Later processes—synaptogenesis, pruning, myelination, and cognitive maturation—refine that architecture but rarely rewrite it wholesale absent a severe, discrete insult. Conflating early developmental windows with later behavioral emergence invites causal error.

Much of what later appears as “regression” may reflect the unmasking of pre-existing vulnerabilities at predictable developmental stress points rather than sudden postnatal injury. In that sense, a substantial portion of neurodevelopment is already “baked in the cake” before birth, even as function continues to evolve across childhood and adolescence.

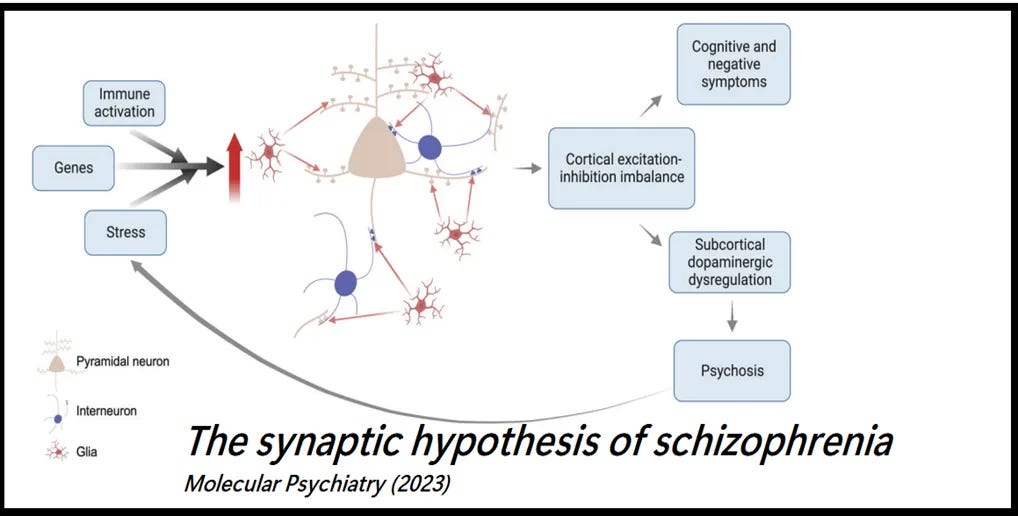

For true postnatal causation to explain regression, one would need a mechanism akin to later-onset neurodegenerative pruning or inflammatory injury, more analogous to schizophrenia or encephalitis than to autism as it is usually observed. Such mechanisms remain unproven at population scale; however, were they to occur, it would be akin to schizophrenia’s onset (discussed in Unraveling Autism’s Surge):

“Schizophrenia, which often emerges in late adolescence, illustrates how dysregulated synaptic pruning -- a process refining neural connections -- can alter brain function, potentially triggered by environmental factors like infections or toxins.”

This does not exclude environmental influences. Epigenetic modulation, prenatal exposures, perinatal stressors, and early-life conditions can all shape expression. But they act on a pre-existing architecture. The evidence to date supports a model in which much of autism is, as you put it, “baked in the cake,” with variability in when and how it declares itself.

Recognizing this distinction matters. It cautions against assuming that temporal proximity implies causation, especially when developmental transitions themselves are powerful unmasking events.

Q5. Why compare autism to tobacco, opioids, asbestos, or concussions?

In health controversies, a harm is identified; a villain is isolated: moral pressure escalates until dissent becomes immoral; settlements follow. Large sums flow reliably to intermediaries even when causation remains contested.

Tobacco litigation followed convergent evidence. Opioid litigation followed a different path, concentrating blame on select firms despite systemic origins. Asbestos policy treated disparate exposures as uniform hazards, collapsing industries with uneven public benefit. Concussion settlements advanced faster than replicated science.

Autism now approaches a similar crossroads. Once a condition is framed as a single liability with apocalyptic cost projections, financial and political gravity takes over. Science becomes secondary.

Q6. Vaccine manufacturers are shielded from liability. Where is the money incentive?

Purdue complied with policy, developed an abuse-deterrent formulation, and was still scapegoated once narratives aligned. Fraud claims, political workarounds, or retroactive reinterpretation can reopen closed doors. My argument is not that this outcome is inevitable. It is that certainty invites it.

Q7. Why criticize Toby Rogers specifically?

Because his claims are unusually definitive and unusually expansive. Rogers asserts that autism and chronic disease epidemics are primarily caused by vaccines and a small set of toxicants ( and vice versa, that all vaccines are autism-ogenic).

He projects multi-trillion-dollar societal costs and advocates for massive compensation under the language of transitional justice. That framing collapses diagnostic heterogeneity into a single causal story and demands institutional rupture rather than accountability within existing systems.

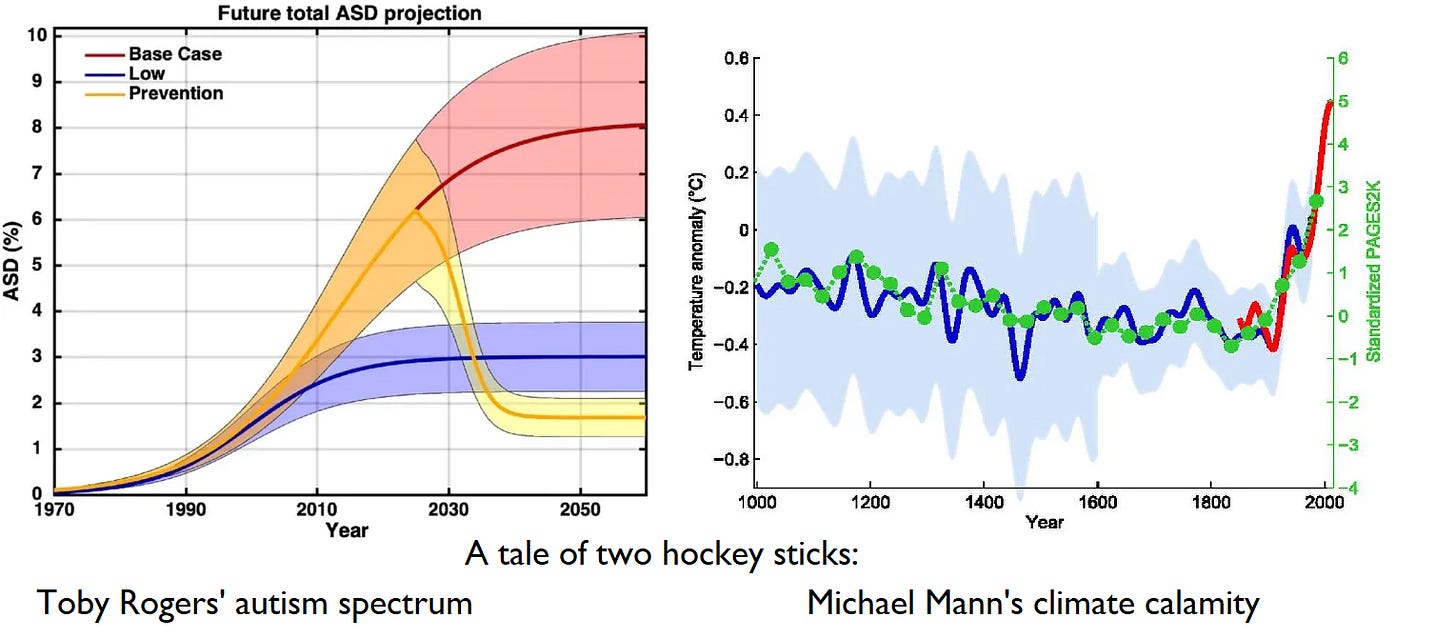

Volume of citations does not confer validity. Science advances by weighing conflicting evidence, interrogating assumptions, and remaining open to revision. Hockey-stick projections derived from selective windows are predictive analytics, not adjudicated science. When dissent within dissidence is met with dismissal rather than engagement, the warning signs are already present.

Conclusion

I do not argue that vaccines are harmless.

I do not argue that autism is purely genetic.

I do not argue that environmental contributors should not be investigated.

I argue that collapsing a complex, historically fluid diagnosis into a single toxin-driven morality tale is intellectually reckless. It invites premature closure, misdirected remedies, and the empowerment of the most absolutist voices.

When resistance hardens into doctrine, it stops being corrective and starts becoming dangerous.

https://randoctor.substack.com/p/autism-vaccines-and-the-diagnostic

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.