Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

From a lifestyle perspective, the time period between Thanksgiving and New Year’s is, let’s face it, rough. There’s the food, the parties, the cold weather keeping you indoors, and of course, the alcohol. It’s no wonder many of us wake up January 1st thinking “ok, something’s gotta change here.”

Is “Dry January” the answer?

Dry January was officially started by Alcohol Change UK in 2013, but it has grown dramatically from just 4000 registered participants in the inaugural year to millions (both officially and unofficially) today.

I get why it is so attractive. The new year always brings a renewed focus on health, and there’s something that seems... approachable about taking a month off from alcohol. It’s not forever; if anything, you’re sort of proving to yourself that you can do it. And the social nature of it helps. You have friends who are doing it. The social media feeds are filled with #DryJanuary hashtags.

But… does it actually do anything? Are there clear, physiologic benefits to a month (a mere month) of withholding alcohol? Or is it just a fad? Or worse, does participating in Dry January make you drink more in February or the rest of the year?

Pour yourself a cold glass of… milk and we’ll dig in.

Let’s dive into the Dry January literature to figure out if this is all hype or something that might be worth your time here in 2026.

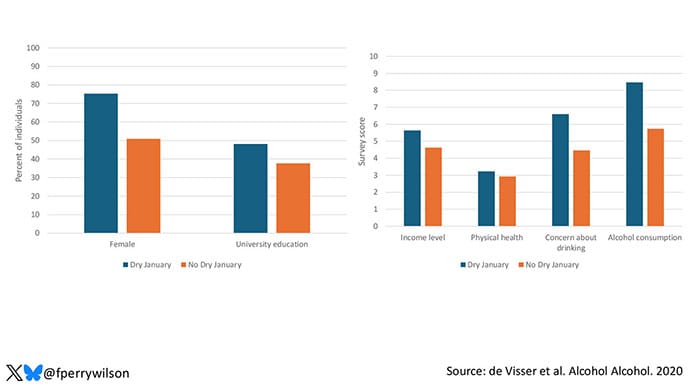

First, I need to get something out of the way which will color how we interpret these data moving forward. People who do Dry January are a very particular sort.

Broadly speaking, they are much more likely to be female. They have higher incomes and are more likely to be college-educated. They also drink more alcohol than the average person. They are “health-conscious hazardous drinkers,” and though some may meet the official criteria for alcohol use disorder, few would refer to themselves as alcoholics.

We need to keep this in mind when we look at the effects of Dry January. Because, as you’ll see, there are a lot of potential benefits but also some risk, including withdrawal (which can be fatal) in particularly heavy drinkers.

Of course, you won’t see any benefits if you don’t actually do it, but success rates are surprisingly high. About two-thirds of people in the UK and 80% of those in the Dutch version of Dry January called “IkPas” made it through the month without drinking.

Interestingly, analyses of social media show much worse success rates. An analysis of Twitter posts about Dry January found that only 12.7% indicated success, while 66% indicated some kind of failure. But you don’t need me to remind you that social media is not real life.

So, assuming you can successfully navigate the month of January without alcohol, will it make a difference?

The data are actually fairly impressive across several domains.

Let’s start with the liver. In 2017, researchers enrolled 64 heavy drinkers in a 4-week abstinence program. At baseline and at the end of the month, they measured the liver stiffness (using a noninvasive FibroScan device). The effects were pretty dramatic — 80% of those who abstained from drinking saw an improvement in liver stiffness — on average around a 15% reduction. In fact, the results were so impressive that the authors concluded that the FibroScan device may overestimate liver stiffness during active drinking because it was hard to imagine why improvement would occur so rapidly.

But I think this might be real, not necessarily in terms of improving liver fibrosis — that probably does take more than a month — but in terms of improving liver inflammation. This small study showed significant improvements in liver enzymes after 4 weeks of abstinence, for example.

Of course, alcohol is not only bad for the liver. One oft-overlooked fact about alcohol intake is that it has a lot of calories, 7 calories per gram actually, making it more calorie-dense than carbs or protein and only slightly less calorie-dense than fat. Participants in Dry January tended to lose a bit of weight — around 3 pounds over the month. It’s not a GLP-1, but it’s not bad.

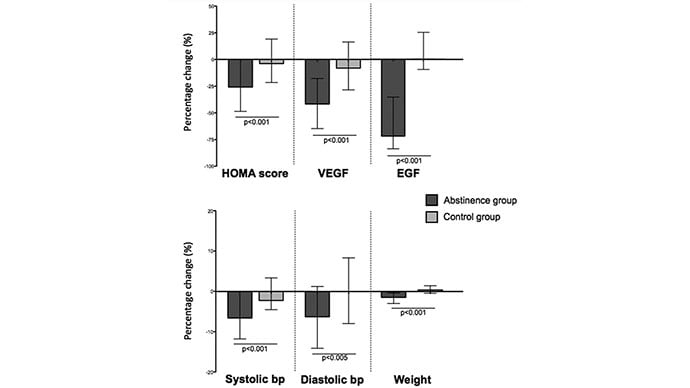

Some studies have shown even more dramatic biochemical changes after a month without alcohol. This study in BMJ Open compared 94 Dry January participants to 47 who kept drinking. The abstinent group had a 25% improvement in insulin resistance and a 7% reduction in systolic blood pressure. Maybe more surprising, those who held off the sauce had a 42% reduction in VEGF levels and a 74% reduction in EGF levels — these are both biomarkers that have implications for cancer risk.

Sleep quality dramatically improved during Dry January, when 71% of participants in the UK reported sleeping better and having more energy.

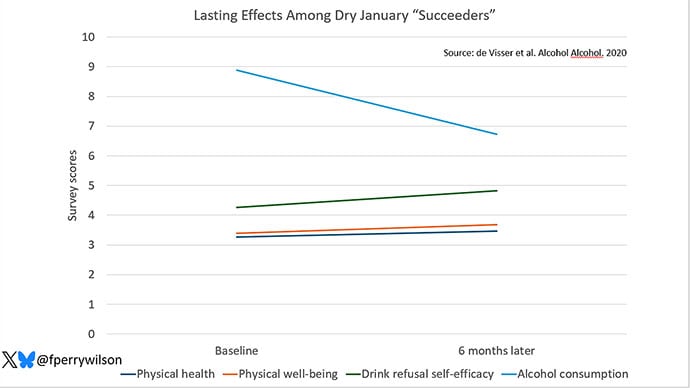

To be honest, it was hard for me to find a physiological metric that doesn’t improve during Dry January. But that didn’t answer my biggest question, which is what happens when Dry January ends?

According to data from the UK, there are some lasting changes. Researchers looked at Dry January participants in August to see how their relationship with alcohol had changed. Overall, it was positive. In August, they had reduced their drinking days per week from 4.3 to 3.3. They drank less alcohol when they did drink, and their days of being drunk decreased from 3.4 to 2.1 per month. So, far from a rebound effect or even a return to pre-Dry January baseline, we see some measurable changes down the road.

We can speculate about why this might be. It may simply be that Dry January proves to individuals that they don’t need alcohol. They can navigate social situations or stressors without it. This is really about self-efficacy. But there is power in proving to yourself that you can do something, and clearly some of the habits built in January may carry throughout the whole year.

Because it’s Dry January, I’m going to devote all my columns this month to alcohol, in some form or another. Next week, we’ll look at the still mysterious ability of the GLP-1 weight loss drugs to curb alcohol intake and the implications that has for our health in the future.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He posts at @fperrywilsonand his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.